|

I recently visited Monrovia, which in the words of P-Square, chopped my money. Food, accommodation, and transportation are much more expensive in Liberia than in any other West African country I have visited. It’s true that Liberia is a post-conflict country full of UN staff, who, when not struggling to help Liberia maintain its stability and get on its feet, are probably struggling to find enough things in Liberia to spend their money on. But Liberia also differs from other countries in West Africa in that the U.S. dollar is used in parallel to the Liberian dollar. Is it possible that dollarization could also contribute to higher prices? First, a couple of observations about money and prices in Liberia. The U.S. dollar and Liberian dollar are used interchangeably. There is no place that accepts only one. Generally, the U.S. dollars are used as large denomination bills, and the Liberian dollars are used in place of U.S. coins. (I didn’t see a single coin in Liberia.) Prices of imported goods in Liberian supermarkets are roughly the same as the dollar equivalent of prices of imported goods in Ghanaian supermarkets. Gas prices also seem to be similar, though a bit more expensive. It seems that the main difference in prices stems from differences in prices of services.

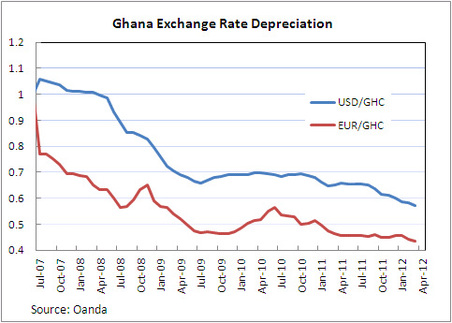

The fact that price differences are concentrated in services, or non-tradeables, makes me suspect that the high prices are in part due to dollarization, and here is why: in a non-dollarized economy, like Ghana, which uses the cedi, if the Ghanaian government pursues a loose monetary policy, the currency will depreciate relative to the U.S. dollar. This doesn’t affect the dollar price of imported goods—these are bought in dollars, so their price in Ghana cedis will just be inflated so that the equivalent price in dollars is unchanged. Other prices in the economy, however, are sticky. Employees have contracts with set wages, and people are used to paying a given price for hiring someone to sew a dress. As a result, the price of these non-tradeables stays constant in cedis, but becomes cheaper in dollar terms. (Note about monetary policy transmission in West Africa: In West Africa, business and consumer loans are much scarcer. So loosening monetary policy doesn’t lead to cheaper credit very quickly. It does, however, mean that cedi funds are more readily available to banks than U.S. dollar funds, which puts pressure on the exchange rate. So monetary policy transmission through exchange rates is more important in countries like Ghana, and happens more quickly, relative to transmission through interest rate mechanisms, compared to countries where large portions of the population have access to credit.) What this means is that Ghana, if has a trend of depreciating currency, can have low overall prices in dollar terms because, in dollar terms, prices for non-tradeables have fallen. Liberia, since it is dollarized, won’t see this effect. If Liberia prints more Liberian dollars, the exchange rate may change, with the value of the Liberian dollar declining, but prices in dollars will stay the same. This does, of course, attribute a level difference to an effect that applies to differences in rates of change, and my observations regarding prices of goods and services are anecdotal (Liberia doesn’t have good CPI data.) If you have comments on the plausibility of the theory, please comment!

5 Comments

Clearly, the nations of the world are not going to line up to let me randomize their monetary policy. But what if I could convince one to do so?

Randomized control trials (RCTs), when ethical and possible, present the most reliable way to measure the impact of policy. Units of randomization, for instance people, are put into a treatment group, who gets a program or policy, and a control group, that doesn't get the program or policy. You compare outcomes for the two groups to see the impact of the program. The key to the validity of the RCT is that the sample size has to be big enough that when you randomly divide into treatment and control, there are no important systemic differences between the two groups. Randomization isn't used to evaluate macroeconomic policies for 2 reasons: 1) it is usually too important for people to allow it to be randomized, and 2) it has to be enacted at a high level-- national or maybe state or province-- so it is difficult to get a large enough sample. But what if we randomized, not by entities like people or countries, but across years? For example, what if the Federal Reserve allowed me to randomly change the policy interest rate by +25 basis points, 0 basis points, or -25 basis points? Over a long enough time frame, the periods that fall into each randomization group should be statistically the same on average. This would allow us to look at the effect of the interest rate change on the economy. Of course, there are some kinks to be worked out. Similar to spillover effects, policy changes have impacts across multiple periods; however, these could be measured and accounted for. Another problem is checking the balance of the randomization. There would be no equivalent to a baseline, and you couldn't stratify, since you don't know the attributes of future time periods in advance. These problems would imply that you need a very large sample size. There are certainly other methodological challenges I haven't thought of. I imagine I will have plenty of time to think through them before the first problem-- the fact that politicians, who insist they can control things they can't, would never randomize something they can-- is solved. But if anyone hears about a central bank looking for a monetary policy consultant, let me know. The Ghana Cedi has depreciated noticeably in recent months. Similar depreciations were seen in 2000 and 2008, which, like 2012 were election years. (In 2004, also an election year, the cedi did not depreciate much.)  By the way, the actual currency code for the Ghana cedi is GHS. GHC refers to the old cedi. International finance nerds love currency codes. Does the Ghana cedi experience election year blues? If so, why? To address this question, I examine a few alternative explanations for the depreciation of the cedi: 1. The cedi depreciates in election years due to uncertainty about Ghana’s political and economic future. Uncertainty could result in cedi depreciation if it leads investors to pull their money out of Ghana, or to hesitate to invest in the first place. With the lead-up to the election looking more tumultuous than previous elections, and recent unrest in other West African countries, it would seem investors have reason to be cautious. It’s hard to find data to test this theory right now, as foreign investment data usually come at a lag. Foreign investment was strong in 2011 compared with 2010, but that says little about developments in the last half year or so. Uncertainty could also lead to depreciation if the cedi falls under speculative attack. The Bank of Ghana has attributed some of the depreciation to speculation that drives down the value of the cedi. (http://www.bog.gov.gh/privatecontent/MPC_Press_Releases/50th_MPC_Press_release-_Final_Copy.pdf) 2. The cedi depreciates in election years due to politically-motivated expansionary monetary policy by the Bank of Ghana. The incumbent party would benefit from a strong economy come election time. Short-term economic growth can be encouraged through expansionary monetary and fiscal policies. Increasing the money supply, however, eventually leads to inflation, which hinders the economy. The Bank of Ghana has actually raised policy interest rates in recent months, but you can’t necessarily look at policy interest rates alone to see if monetary policy is expansionary. Here’s why: the government of Ghana has been spending a lot of money (typical of an election year.) Normally, this would push up the government’s borrowing costs, and raise interest rates generally. However, if the central bank keeps rates constant rather than letting them rise, this has an expansionary effect. A better measure to look at is inflation. One-year inflation rates appear to be pretty steady, but these do not reflect very recent trends. The trouble with looking at monthly inflation is that prices in Ghana are highly seasonal, rising in the spring and then falling after harvest, and seasonally adjusted series are not released. Inflation in January and February was only somewhat higher than inflation in those same months over the last few years. While the key statistics that would be indicative of expansionary monetary policy are inconclusive at this point, the Bank of Ghana does acknowledge some other indicators of looseness. The Bank mentions that credit has eased, meaning money is easier to get, and that starting in 2011, there have been signs of liquidity overhang—meaning that banks have more cash than they want, causing interest rates to fall. The Bank mentions that these lower interest rates on cedi assets could be driving investments to other currencies with a higher rate of return. 3. The cedi depreciation is only coincidental to the election year, and is driven by other factors, including global economic conditions. There are some other factors that could be driving cedi depreciation. The first, mentioned by the Bank of Ghana, is that the depreciation is driven by demand for foreign currency to buy imports. Despite strong exports of oil, gold and cocoa, Ghana’s imports are growing faster than exports. A second possibility is that economic trouble in Europe is having a negative impact on the funds that are available to go to Ghana. This could account for a decline in investment in Ghana, if indeed such a decline is occurring. Remittances, however, appear to have remained robust, according to the Bank of Ghana. So what do I think? I think it is possible the election is having an effect, either on foreign investment, or on speculation in the currency market. I also think that the Bank of Ghana’s policies, politically motivated or otherwise, are responsible for it. While political turmoil is hard to address, a central bank can easily punish speculators and attract investors by raising interest rates. It appears that the Bank of Ghana is now taking steps to do just that, but earlier action might have nipped the depreciation and any speculation in the bud. My guess is that growing imports and a stagnant global economy may play roles, but not central ones. The West African CFA Franc, for example, has actually risen against the dollar since the beginning of the year. This suggests that at least some of the cedi’s downward trend is specific to Ghana’s. Luckily, that means that Ghana has the power to change it. After years of remaining a theoretical plaything for money nerds like me, nominal GDP targeting has suddenly become a thing. NGDP targeting has been getting love from economists across the political spectrum, which naturally means laypeople across the spectrum are responding with skepticism. Drudged up from what I remember from Prof. Burdekin's Money and Banking, I present the basics of NGDP targeting:

What is NGDP targeting? NGDP targeting means that the central bank sets monetary policy to target nominal gross domestic product, that is, GDP that is not adjusted for price level. The beauty of NGDP targeting is that since both prices and output are part of NGDP, both of these things influence monetary policy even though only one metric is considered. Either NGDP level, or growth, can be targeted. Why liberal economists like it: liberal economists tend to be more supportive of considering economic growth, not just inflation, when setting monetary policy. NGDP targeting naturally includes growth as an input. Why conservative economists like it: conservative economists tend to prefer simple, transparent rules for monetary policy, as opposed to opaque systems that give broad discretion to policy makers. NGDP targeting is easy to understand and easy to see if policy makers have met their goal. So how is it different? The Federal Reserve has what’s called a dual mandate—they are charged with considering both prices and economic output when setting policy. (Some central banks, like the European Central Bank, are charged with only considering prices.) The Federal Reserve does not commit to following any particular formula for setting monetary policy, but it is largely believed to behave as if it follows the Taylor Rule, meaning it considers deviations from target inflation rates and target employment rates. Targeting NGDP would provide the Federal Reserve with a mandate to specifically target deviations from output targets. There are other things a central bank can consider besides prices, employment, and output when setting policy, such as money growth and asset prices. A central bank with broad discretion can consider all of these things, but this comes at the cost of making monetary policy decisions less transparent. But what about QE2?? So where do things like quantitative easing fit into all this? It is important to distinguish between the tools used to set monetary policy and the tools used to implement monetary policy. Tools used to set monetary policy, such as Taylor Rules, money growth target, or NGDP targeting, tell the central bank whether they need to tighten or loosen policy. The tools used to implement monetary policy generally remain the same regardless of what policy prescription tool you use. If interest rates are at zero, and inflation is low and unemployment high, you need quantitative easing to get to your targets. If interest rates are at zero and NGDP is below target—guess what, you still need quantitative easing to get to your target. Targeting Growth vs. Level If you are going to target NGDP, you have to decide whether to target NGDP growth rate or NGDP level. Most of the cool kids in economics prefer level targeting. Level targeting has the benefit of allowing for catch up periods: after the economy has had a downturn, it natural that it have a period of both higher growth and inflation to catch up to where it would have been pre-downturn. So let’s do it? To me, whether NGDP targeting should be implemented actually involves three different questions: 1. Should GDP be considered when setting monetary policy? The downside to considering GDP or other factors is that the central bank places less weight on price stability, which is bad if you are an inflation hawk. The benefit is that drops in GDP often lead drops in inflation or unemployment, so considering GDP can help the central bank adjust to new economic trends more quickly. 2. Should the central bank target levels rather than growth rates? When it comes to prices, levels are arbitrary—it’s change in prices that matter. That’s the primary logic behind targeting inflation rather than price level. However, as discussed above, it is natural for an economy that has been sluggish for a while to have a period of higher growth and higher inflation to “catch up” after a downturn, so monetary policy that accommodates this can make sense. This accommodation can actually help end a downturn more quickly—if during a downturn, people know they can expect extra high inflation in the future, they have an incentive to spend more now, stimulating the economy. The flip side to all this, which I haven’t seen discussed much, is that monetary policy lags the trends a bit. This sounds great when you are coming out of a recession, but what about when you are coming out of an expansion? Would the people keen to see accommodating monetary policy continue as growth picks up be equally keen to see tight monetary policy stay in place when growth comes to an end? 3. Should the central bank have a clearly defined rule? The benefit of a rule is that it provides transparency and sets expectations, and expectations are essential for effective monetary policy. The downside of a rule is less flexibility, and loss of credibility if the central bank fails to meet its targets. If you answered yes to all of the above, then NGDP level targeting is for you. Personally, I agree that a central bank with a dual mandate should consider GDP. However, I think that the central bank should have some flexibility in targeting levels versus growth, and that growth is sometimes the more appropriate metric. Moreover, I think that a central bank like the Federal Reserve, that has a high level of trust and credibility, has more to lose from committing to a rule like NGDP level targeting than it has to gain, since failure to achieve the target would hurt its credibility. As it is, the Federal Reserve can consider the policy prescriptions of an NGDP target, while also considering Taylor Rules, asset prices, and other economic data when setting monetary policy. I have no quantitative evidence to support this, but I get the impression that prices are stickier in Ghana than in the United States. My theory is that this is, ironically, because Ghana lacks sticker prices.

Most people buy things in the market, and they just "know" the price. If someone tries to charge them higher, they won't buy. My guess is that changing common knowledge of a price is actually a lot harder than just changing a sticker price. Could somebody do a study on this please? I recommend an RCT in isolated markets where you select half of the markets to go to sticker prices, where you provide the stickers. Those markets operate with the stickers for a few months, where the control markets continue to operate without marked prices. Then you introduce a price shock for, say, tomatoes, send out mystery shoppers, and see where prices change more quickly. I would do it myself but I am busy. I am currently obsessed with change. Going to the market is an exercise in retaining as much small change as possible.

I was warned to jealously guard my one cedi notes and coins, but I did not realize how important this would be until I was trying to buy lunch the other day. I walked up and down the street, but no one could sell me fried cheese or avocados and give me change for my ten cedis. I was starved by the time I decided to go to the canteen and buy a full plate of jollof rice. Although my problem with small change is likely exacerbated by the disparity in income between me and most of the people living in Tamale (I take 100 cedis (about $70) out of the ATM at a time, where many people may earn only a few cedis a day), I believe the lack of small change is a problem for everyone. Many things are sold for less than 1 cedi, yet 10 cedi notes are prolific and coins are rare. I have heard there are businesses that will trade you 9 one cedi notes for your 10 cedi note. This problem may also be related to the recent re-denomination of the cedi; several years ago they chopped four zeros off the currency; what sold for 10000 cedis is now 1 cedi. Spotted this question on Yahoo! Answers (I was looking for examples of non-moral values but that's another story):

What is NOT a function of the Federal Reserve? A. Giving short-term loans to banks B. Controlling the money supply C. Regulating depository institutions D. Lending money to businesses for investment This is an intro to macro classic. If you said D, that was the correct answer. At least until the financial crisis. Some of the recently added facilities look like they could fall into that last category. For example, the Commercial Paper Funding Facility, which buys commercial paper directly from issuers. That sounds a lot like "lending money to businesses..." Time to add E. None of the Above The Reserve Bank of Australia became the first G20 central bank to raise interest rates today, increasing its policy interest rates by 25 basis points to 3.25%. Of course, Australia has done very well through the financial crisis, relatively speaking. It's banks have remained pretty strong, China has continued to demand Australia's commodity exports, and Australia has only had one quarter of negative GDP growth. (Australia's real GDP fell 2.8% at an annual rate in 2008Q4. while in the United States, recessions are declared by the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee, many countries simply consider a recession to be in effect after two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth.)

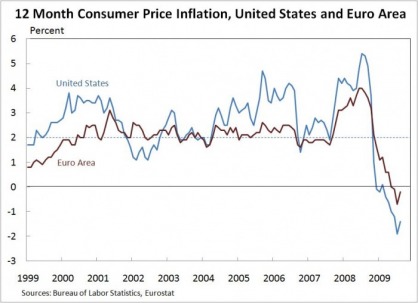

The RBA's decision to raise interest rates resulted in a drop in the dollar. With Australia raising interest rates, investors know that there are assets out there where they can get higher returns, so low-yielding Treasuries don't look like such a good deal, despite their safety. The decision is also a vote of confidence in the world economy, which could increase investor's expected returns on assets other than Treasuries. As Australia and other countries (possibly Korea?) start raising interest rates ahead of countries like the United States and Japan, keep your eye out for a revitalization of the carry trade, where investors borrow in countries with low interest rates, and invest in countries with higher interest rates. One of the House Financial Services Republicans' financial regulation reform proposals is increased oversight of the Federal Reserve, including an explicit inflation target. Explicit inflation targets, where the central bank announces a specific inflation rate it intends to achieve, are used by a number of central banks around the world, including the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, both of which aim for 12 month consumer price inflation near 2%. In recent years, the European Central Bank has managed to keep inflation closer to 2% than the Federal Reserve. However, targeting alone doesn't tell the whole story. The European Central Bank is charged with considering price stability first, and economic growth second. The Federal Reserve is supposed to consider both equally. Thus, one would not necessarily expect the two monetary regimes to have identical inflation rates, even if they were both explicitly targeting 2% inflation.

An explicit inflation target can be useful to help build confidence in a central bank and ground inflation expectations-- if the central bank can meet the target. If it can't, the central bank risks losing confidence. Among central banks, the Federal Reserve may be least in need of building confidence, due to its long, respected record. If public confidence in the Federal Reserve were to falter, implementing an explicit inflation target might help. However, even though the Federal Reserve has become the target of some public blame for the financial crisis, markets appear to still have faith in its ability to maintain price stability. Inflation expectations (which can be gauged by looking at the difference between the yields on regular Treasury notes and the yields on notes indexed to inflation) have remained close to 2% for the medium to long term. This suggests that an explicit inflation target would do little to improve the functioning of the Federal Reserve. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed