|

The London Olympics concluded today. For the first time, women were represented on every competing nation’s team, and the U.S. team had more women than men. Judo gold medalist Kayla Harrison talked openly about being a survivor of sexual abuse, and American soccer player Megan Rappinoe publicly announced she is gay. But these Olympics also demonstrated that we are still struggling with how to react when the people achieving these feats are women:

· Officials considered requiring female boxers to wear skirts. Are you kidding me? I am sure these ladies could kick ass wearing skirts, high heels, or the queen’s hat if they had to, but just because (some) women wear skirts doesn’t mean women need to wear them boxing. You don’t see anyone making male boxers wear cummerbunds. · US weightlifter Sarah Robles struggles to get a sponsor. The US top-ranked Sarah Robles had no sponsors and was living on $400 a month before the games, despite her athletic success and inspiring back story: she has Madelung’s deformity which means her ulna is shorter than normal and crooked, resulting in pain during every lift. She is now sponsored by Solve Media. Her lack of funding highlights the difficulties that athletes in more obscure sports face in finding sponsors, especially if the athlete doesn’t look like our typical ideal of beauty. · Hurdler Lolo Jones gets ripped in NYTimes for having too easy a time getting a sponsor. God forbid a female athlete should actually be good looking, controversial, and use those traits to drum up publicity necessary to get sponsorships and avoid living on $400 a day, though. Lolo Jones was the subject of a highly critical NY Times article alleging that her fame was due to looks and public discussion of her choice to remain a virgin, rather than her athletic abilities. While it would be great to see more coverage of her teammates who medaled in the event, she placed fourth—it looks like she was pretty qualified to be at the Olympics. It’s obvious that getting sponsorships relies not only on athletic performance but also on charisma, but it seems that female athletes get disproportionate criticism when they play the game. Lolo’s idiosyncrasies give her an unfair advantage in the media circus—but Ryan Lochte’s grill gets a pass. · Gymnast Gabby Douglas’s ponytail isn’t good enough. I sometimes don’t comb my hair in the morning. Gymnast Gabby Douglas, gold medalist in the women’s all-around, hits the floor to complete some of the most difficult physical maneuvers on the planet, and it’s a travesty that more thought, time and effort didn’t go into her hair. What, the U.S. gymnastics team didn’t want to hire Ronaldo to consult? · Will beach volleyball keep the bikinis? In a number of sports, athletes compete in minimal attire for the sake of comfort and ease of movement. When beach volleyball, whose traditional attire is obviously beach wear, allowed women to compete in more covering uniforms, an inordinate amount of attention was paid to which women would keep their bikinis. What should have been a simple choice reflecting weather and personal preferences would inevitably be viewed as a statement on gender, voyeurism, and the image of the sport. · IOC institutes policy of gender testing based on testosterone. The test would only be carried out if requested by the chief medical officer of a national Olympic committee or a member of the IOC’s medical commission. They have not published an acceptable level of testosterone, and the methodology has been criticized by some doctors, as some women simply produce high levels of testosterone. Some fear that gender testing will unfairly single out athletes who don't conform to tr Castor Semenya, a South Africa female runner whose gender was questioned three years ago and was subsequently cleared, competed and won the silver medal in the women’s 800 meter run.

1 Comment

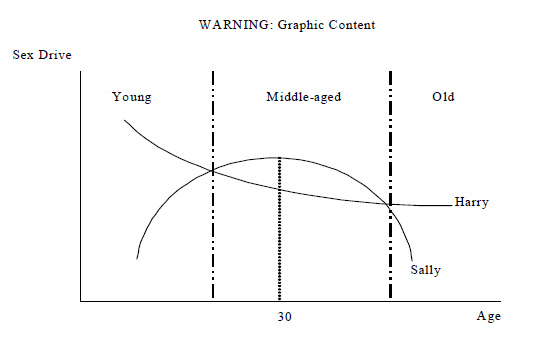

This is possibly the most awesome economics paper I have read in a while, containing the most awesome graph I have seen in a long time:

I’m a bit late responding to the whole DNC something Hilary Rosen’s statement that stay-at-home-mom Ann Romney “never worked a day in her life.” While I understand that Rosen intended the statement to be a reference to Ann Romney’s socio-economic status, the statement was insulting to moms who work hard raising their children and managing their household.

Let’s be clear: denigrating the works it takes to raise a family and manage a household is not feminist—nor does it do anything to help mothers who work outside of the home. Feminism is about making sure that men and women have the same opportunities. Those opportunities should include taking care of a family. Discounting the value—and difficulty—of work in the home doesn’t do anything to encourage policies that let working parents balance their work and home responsibilities. Discounting the value of work in the home doesn’t do anything to encourage men to take on more of the work raising families. The debate about stay-at-home-moms versus working moms is meaningless. Raising a family is difficult, whether you are working for a paycheck to support the family, working in the home, or both, and the main factor that determines how difficult it is is economic opportunity. What matters, assuming we think the family is an important aspect of our society, is getting people to place greater value on the work it takes to manage a family, and pursue policies that lessen that burden. I think Michelle Obama said it best with this tweet: “Every mother works hard, and every woman deserves to be respected.” My last night in Ouagadougou, I enjoyed a lovely Vietnamese dinner, then went to the street to find a taxi to my hotel. It wasn’t late, but it was just starting to rain, and taxis were scarce, so I started walking in the direction of the hotel, knowing I would be more likely to find a taxi that way.

I was crossing an intersection when a man started yelling “La blanche! La blanche” (White! White!) I decided to ignore him, as this rude by any measure. The man then ran up behind me, and grabbed me around the neck with both arms. I had no idea what he was doing, so to be on the safe side, I screamed. I was able to duck out of his arms and push him away. He didn’t put up much resistance, so I decided this was just his idea of sport. I hit him across the face, then walked away, and he let me go. Hitting an assailant wasn’t the smartest thing—I probably should have taken off running—but I’m glad I did. What was he thinking? He didn’t strike me as being mentally ill in any way. The only conclusion that I can come to is that since I was clearly a foreigner, and because he thought I was physically weak, he felt like he could get away behavior that would be unacceptable in his own community. The more disturbing thing is that, even though there were half a dozen people in the immediate vicinity, no one did anything. No one tried to help, or even asked if I was okay. This was shocking to me, especially because in Ghana, people would have come running from all around. I’m not sure why no one helped—if it was because it was beginning to rain and they wanted to go home, or if it was because I was a foreigner, or if that’s just the culture in Ouagadougou. If you are reading this and thinking, “Poor Liz—what a god-awful country!”, then I have news for you: men do stuff like this to women all the time in the United States, and they get away with it. Ask any young woman living in a city like New York or DC when the last time was that she was catcalled on the street, or grabbed in a bar or club. Ask her if anyone said anything to the person who did it. The fact is, wherever conditions exist that allow people to harass others without consequence, there will be people who take advantage of that. I think there are two cultural tendencies that contribute to those conditions: 1. A general tendency not to get involved. This is something that you see a lot more in the west than in places like Ghana, where society values individualism less and communities are tightly-knit, creating more incentive to enforce good behavior. But everywhere, to some extent, people are often hesitant to get involved, either because of fear, or because of inconvenience. The result is that bad behavior goes unpunished. This is especially consequential in places where formal law and order is lacking. 2. In-group bias. I think that everywhere, people who are “different” are more likely to be targeted and less likely to be helped. (They are probably more likely to be targeted BECAUSE they are less likely to be helped.) These people might be vulnerable because they don’t speak the local language, and don’t have local social connections or social standing, but I think there is also a tendency for people who are different to be more objectified—they are seen first as “a white” or “a black”, rather than as another person. People have less problem with them being objects for others’ amusement, and they are less concerned with their welfare than they would be someone who appears to be from their same community. There are people who would argue that in-group bias is okay or even good, and that it encourages social cohesion. I argue that the cost of in-group bias is that the most vulnerable people are ignored when they need help. So if you don’t like what happened to me, I urge you to do two things. First, make yourself more of a “social enforcer.” Being a social enforcer can be intimidating. Natural social enforcers often have a high tolerance for stress. But generally, a person who enforces good social behavior, for example by chiding someone who cuts in line, are viewed favorably by everyone who observes the interaction. Second, try to fight your own in-group bias, and make an effort to reach out to those people who seem especially out of place. If they look out of place, they probably feel that way even more so. Treat them the way you would want your mother, or your sister, or your daughter treated if she were alone someplace strange. Interestingly, the two things I am encouraging—social enforcement and reducing in-group bias—are typically associated with opposite sides of the political and social spectrum. Social enforcement tends to be associated with conventional, authoritarian, and duty-oriented attitudes. Reduced in-group bias tends to be associated with liberal, individualistic, and intellectually-oriented attitudes. I don’t think this is an accident: all of these values are good; that’s why there are people that value them. If we all ascribe to each other’s values a little more—if social enforcers can apply their protections to a wider group of people, and if those who care about people who are different can make themselves into social enforcers—I think we would do better at protecting the most vulnerable from those people who have no values at all. Last night, I was traveling by trotro from Kintampo to Tamale. We stopped at a police check point.

"Driver, close your boot!" I saw them pack the boot (what they call the trunk here). There's no way the boot is closing. Damn. That means I have to flirt with the other officer, who is yelling "My wife! My wife!" at me. I ask his name and tell him that I have to go to Tamale, and the faster we go the faster I can come back and marry him. We are waved on our way, along with our still-unclosed boot. When people think about corruption, they often think about it in terms of money. If your boot can't close, you pay a small dash so the officer will let you continue your journey. If you want a driver's license, you pay a dash to get it done in one day rather than three. If you overstay the 60 day limit on your visa, you pay a dash to avoid a renewal process that is very costly in terms of time and effort. But there is another currency that those who extort bribes will often accept: flattery and flirtation. I have never paid money to police at a checkpoint, but I have paid in smiles, jokes, and fake email addresses. Is this a good thing? I'm not sure. At its best, it feels like nothing more than being friendly, and the person you are interacting with can go from being a hurdle to a helper. At its worst, deferring to or faking interest in someone who is clearly on a power trip feels degrading. An interaction like the one with the trotro leaves me feeling like I have prostituted myself in small way, and more than I hate that authority figures have the power to extort money, I hate that they have the power to extort me as a sexual or romantic object, even if only in very small ways. My conclusion is that corruption is not about money, it is about power. You can reduce the bribes paid to zero, and still have corruption. That means that focusing on punishing people for taking bribes won't solve the problem-- graft will be paid in other currencies, such as favors. Fixing corruption is about limiting the discretion of individuals--setting up systems with clear rules and expectations-- to take away their ability to extort anything, be it money or my Facebook name. _ Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE MicrosoftInternetExplorer4 /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Table Normal"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin-top:0in; mso-para-margin-right:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:10.0pt; mso-para-margin-left:0in; line-height:115%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif"; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;} Looking at antenatal care stats for health facilities in Ghana always puts my problems into perspective (OMG my avocado is not ripe!!). Some highlights from the records I looked at today:

Birth years of women attending ANC: The oldest was born in 1970, the youngest in 1999. Educational attainment of women attending ANC: Most have no school; only one had been to high school. How women attending ANC got to the clinic: Women come by walking, tro tros, bicycle, riding on the back of motos, and canoe. In today’s data, the extreme athletics award goes to a woman, 8 months pregnant, who walked 180 minutes to get to the clinic. Eliot Spitzer writes that the state of American men's tennis is a metaphor for the state of the U.S. economy. The article isn't well executed-- he makes a detour into causation vs. correlation just to take a dig at deficit hawks. (Maybe we wouldn't have a demand problem now if we hadn't been spending beyond our means for years and years??) His final point is somewhat valid though-- America is less dominant in tennis and in the world economy because other nations have made gains, and the competition is stiffer, and that's a good thing.

What I take from this is that it is no longer the default that white American men will stay on top. (Spitzer glaringly fails to analyze the state of American women's tennis.) Neither a Grand Slam trophy, nor a big screen TV and two cars, are the inherent right of an American man. Like everyone else in the world, if we want to succeed, we need to make ourselves competitive. This weekend, after a delicious dinner, some friends and I visited a rooftop drinking spot in Osu. As I slowly drove my motocycle into the crowded parking lot, a man reached out, put his hand on my leg, and slid his hand up my skirt as I went by on the moto. It took me a moment to register what had happened, and by that time, I had passed the group of men, and wasn’t even sure who had done it. After fuming for several minutes, I joined my friends, had a double whiskey, and did my best to forget about the incident and enjoy the rest of the night.

As I write this, several days later, I am still furious—furious with the man, but more furious with myself for failing to give the man any disincentive to repeat his actions. The options were many: yell at the man; report him to the police; hit him; run over his foot with my moto; or in my most vengeful fantasy, castrate him with my moto keys. Why didn’t I do any of these things? It wasn’t that I am incapable of standing up for myself. For the most part, it was simply because I wasn’t quick enough to react, but riding away had its advantages: I wasn’t physically hurt, I got out of a potentially harmful situation quickly, none of my friends had to be involved in a mess, and I was able to move on and continue my night. It’s hard to imagine a better outcome had I chosen to confront the man—but at what cost did this efficient short-term result come? What does it take to prevent this type of behavior? Minor physical assault and sexual harassment is not uncommon in Accra. My recent experiences include: · A man grabbing me around the waste and pull me away from my friends to try to get him to dance with me at an outdoor dance spot. I peeled him off of me and started yelling at him; another Ghanaian intervened and convinced him to leave us alone. · A man repeatedly came up to my friends and me in a dance club and rubbed against us, even though we were not dancing. After asking him three times to stop, I told him to “F-k off” and shoved him. He drunkenly fell on the ground and then went away. · A man on the street grabbed my hand as I was walking by him one evening and would not let go. I dug my keys into his wrist as I twisted my hand free. He let me go on my way. Let’s be frank—women face these types of encounters everywhere. I have a close friend in New York for whom catcalls are a humiliating but regular part of her daily commute. She has experimented with every type of reaction I can think of: anger, humor, honest conversation, and simply ignoring it. Nothing seems to make a difference. Is a man with a key gouge on his wrist less likely to try to grab a woman’s arm than one who got away unscathed? The truth is, I don’t think any reaction from a victim of harassment is enough disincentive to put a stop to this behavior. To be an effective deterrent, punishment must come from broad society. Men who sit on steps and catcall in New York City should face the disapproval of the grandmother next door and the scorn of the respectful men who pass by and see them as the boys they are. Men who assault women in Accra bars and clubs should be unwelcome in those spots, and those who grab women on the streets should be ostracized by other vendors there, who face lost business when women avoid those spots. In some cases, this happens. Too often, it doesn't. As long society fails to punish men for this behavior, a they will continue to bet that victims won't punish them either. The project manager on my project is now assisting with a village savings and loan project, and told me some interesting things about working in Bawku, a region in Ghana where violence has broken out between two tribes, the Mamprusis and the Kussassis.

According to my colleague (a Ghanaian), in the first century, the Kussassis, who were traditionally farmers but not fighters, asked the Mamprusis, who were known as warriors, to come to move to their land. In exchange for protecting the area, so the Kussassis could farm in peace, the Mamprusis were given the chieftaincy in the region. The agreement has held for centuries, and in Ghana’s system of parallel democratic and traditional governments, the Mamprusis still hold the chieftaincy, although they are far outnumbered by the Kussassis. The democratically elected official for the region is Kussassi. Several years ago, the Kussassis became unhappy with this arrangement, demanding the return of a Kussassi chief. Violence broke out between the tribes. Despite interventions by the central government, including curfews and prosecution of those perpetrating violence, the situation has remained tense. The Mamprusis control Bawku’s city center while the Kussassis control the surrounding land and villages, and members of the two tribes cannot safely visit the other’s territory, although visitors from other tribes or countries are safe. This situation has posed difficulties for the IPA survey team in the region, as they are trying to collect data in both tribes’ territories. It is crucial that surveyors be hired locally, so they have knowledge of the area, culture, and languages. Since young men on motorcycles have been responsible for much of the violence, the Ghanaian government has recently banned all men in the region from traveling on motorcycles --the chief form of transportation for IPA surveyors. Enter the ladies. IPA surveyors are overwhelmingly male, as it can be difficult to find women with top educational qualifications and a willingness to take on the physically demanding work. In Bawku, the project manager was successful in finding half a dozen qualified women with motorcycles to fill out the ranks of IPA surveyors in the region. Women are not subject to the ban, and can legally ride motorcycles to visit respondents. The team includes women of both ethnic groups, to enable IPA to work in both territories and with respondents of both tribes. The field manager, who will oversee the survey team in that region, is a women of mixed descent, half Mamprusi and half Kussassi, and can safely work in either tribe’s territory. I wish the team the best, and hope that they will demonstrate both the ability of women to be exceptional surveyors and the possibility that people of these two tribes can work together toward common goals. Donald Marron recently bloggedabout a new economics paper on gender arbitrage by multinationals in South Korea. The idea behind gender arbitrage is that discrimination in hiring against a particular group, like women or minorities, creates opportunities for non-discriminating employers to hire talented people for a lower wage. When non-discriminating employers take advantage of this, it should eventually erase the gap in wages between the disadvantaged group and the rest of the labor market. This paper found that multinational corporations have been able to benefit from discrimination against women in the labor market that drives down wages for educated women. In Korea, working women earn only 63% of what working men do. (Not all of this is due to discrimination.) The paper found that among multinationals, a 10 percentage point increase in the number of women in local management positions led to a 1 percentage point increase in return on assets. Marron points out that the fact that companies that hire more women have a hire profit margin means that there is still room for more arbitrage-- implying that discrimination is still resulting in lower wages for women compared with men who have the same skills and abilities.

As unfortunate as it is that women in Korea are being paid less than they are worth, from the perspective of both women and employers in northern Ghana, this is an enviable problem. In Ghana as a whole, about 20% of adult males have secondary education or higher; only about 10% of adult females have that level of educational attainment (source: GLSS 5), and the gender gap is most pronounced in the Northern Region. Traditional views of gender roles still prevent girls from having access to education at the same rate as boys. (Girls may also have a higher opportunity cost of education: girls are often more economically valuable than boys, because they can assist with child-rearing and food processing, or work as maids, at an age where boys are still too young to be much help with farm work.) The result of this is that it is difficult to find qualified female candidates for jobs requiring a high level of education. This is especially apparent to employers like me, who actually have a bias in favor of female employees. Since the majority of the respondents in my survey were female, I wanted to hire female surveyors because they are more likely to put female respondents at ease. Despite actively recruiting female candidates, posting notices encouraging women to apply, and asking the field managers to try to achieve a balance in the number of male and female surveyors we hired, we received few applications from female candidates, and less than a quarter of the surveyors we hired ended up being female. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed