|

I recently visited Monrovia, which in the words of P-Square, chopped my money. Food, accommodation, and transportation are much more expensive in Liberia than in any other West African country I have visited. It’s true that Liberia is a post-conflict country full of UN staff, who, when not struggling to help Liberia maintain its stability and get on its feet, are probably struggling to find enough things in Liberia to spend their money on. But Liberia also differs from other countries in West Africa in that the U.S. dollar is used in parallel to the Liberian dollar. Is it possible that dollarization could also contribute to higher prices? First, a couple of observations about money and prices in Liberia. The U.S. dollar and Liberian dollar are used interchangeably. There is no place that accepts only one. Generally, the U.S. dollars are used as large denomination bills, and the Liberian dollars are used in place of U.S. coins. (I didn’t see a single coin in Liberia.) Prices of imported goods in Liberian supermarkets are roughly the same as the dollar equivalent of prices of imported goods in Ghanaian supermarkets. Gas prices also seem to be similar, though a bit more expensive. It seems that the main difference in prices stems from differences in prices of services.

The fact that price differences are concentrated in services, or non-tradeables, makes me suspect that the high prices are in part due to dollarization, and here is why: in a non-dollarized economy, like Ghana, which uses the cedi, if the Ghanaian government pursues a loose monetary policy, the currency will depreciate relative to the U.S. dollar. This doesn’t affect the dollar price of imported goods—these are bought in dollars, so their price in Ghana cedis will just be inflated so that the equivalent price in dollars is unchanged. Other prices in the economy, however, are sticky. Employees have contracts with set wages, and people are used to paying a given price for hiring someone to sew a dress. As a result, the price of these non-tradeables stays constant in cedis, but becomes cheaper in dollar terms. (Note about monetary policy transmission in West Africa: In West Africa, business and consumer loans are much scarcer. So loosening monetary policy doesn’t lead to cheaper credit very quickly. It does, however, mean that cedi funds are more readily available to banks than U.S. dollar funds, which puts pressure on the exchange rate. So monetary policy transmission through exchange rates is more important in countries like Ghana, and happens more quickly, relative to transmission through interest rate mechanisms, compared to countries where large portions of the population have access to credit.) What this means is that Ghana, if has a trend of depreciating currency, can have low overall prices in dollar terms because, in dollar terms, prices for non-tradeables have fallen. Liberia, since it is dollarized, won’t see this effect. If Liberia prints more Liberian dollars, the exchange rate may change, with the value of the Liberian dollar declining, but prices in dollars will stay the same. This does, of course, attribute a level difference to an effect that applies to differences in rates of change, and my observations regarding prices of goods and services are anecdotal (Liberia doesn’t have good CPI data.) If you have comments on the plausibility of the theory, please comment!

5 Comments

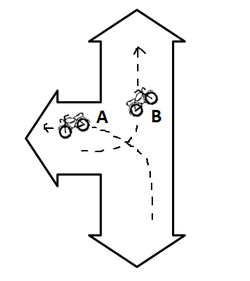

Tamale has a number of traffic norms that would make a driver's ed teacher turn to drink on the road. A classic example is the "Tamale turn", pictured at left. In Tamale, if you are making a left turn off of an arterial, and there is vehicle waiting to turn left ON to the arterial, rather than pass in front of the other vehicle, you pass behind them, while they simultaneously turn onto the arterial. One can see why drivers might think this makes sense. Both vehicles can turn at once, and if the arterial is busy, the vehicle waiting to turn on to it can take advantage of the other vehicle slowing down. But as traffic gets denser, the Tamale turn becomes more hazardous. If there are several vehicles waiting to turn on to the arterial, the vehicle turning off the arterial has to negotiate a route behind the turning vehicle, and in front of the waiting vehicles, who may not be on the lookout for a turning vehicle. And more vehicles in the intersection at once raises the risk of a collision as well. As Tamale's traffic worsens, many similar traffic norms, such as running red lights and passing on the right, technically illegal but general practice in Tamale, will become less efficient and more hazardous. But they will already be ingrained as the standard. What to do? Some ideas: 1. Give driver's licenses based on merit rather than bribes, to give drivers an incentive to learn the rules on the books. 2. Ticket drivers for practices that threaten public safety rather than focusing on trivial offenses easy to convert to payouts. Your additional ideas are welcome in the comments!  "A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It's where the rich use public transportation." If the truth of this statement is not immediately apparent, you probably have never commuted in a West African city. Accra needs a lot of infrastructure improvements, but one thing it does not need are more cars. After work, I can run the two miles to my gym faster than I could take a taxi there. Traffic is similarly bad in Kumasi and Dakar, and is rapidly worsening in Tamale. Driving is no picnic in American cities, either. The difference? In American cities, rich people often choose to live in places accessible to public transportation, and their taxes and patronage support transit systems that benefit the rich and poor alike (even LA is getting on the bandwagon). In developing country cities, the poor take low quality public transit, such as trotros and shared taxis, while the rich clog the roads with their private cars and taxis. While roads in developing country cities could certainly be improved (I would love to see someone apply traffic light efficiency models to Accra traffic), the reality is there is limited capacity to expand current roads or build new ones in the middle of the city. Poor people are already taking public transport. That leaves one viable solution to traffic in developing country cities: getting rich people to convert to public transport. For practical and cultural reasons, this is an uphill battle. First, the main reason rich people use public transport in developed cities is not because they are altruistic, it is because it is faster and easier than driving. Accra currently has no public transit system that can rival the speed and efficiency of a private car. Considerable investment would have to be made in a rail or bus system with widespread coverage and efficiency in order to convince people to convert. Second, there is a cultural attachment to driving. Owning a car is a definitive status symbol in West Africa; taxi drivers are often confused when I, a person who apparently has the money to take a taxi, choose to walk. Improving traffic in Accra will require a commitment from the wealthy and elite-- both foreigners and Ghanaians-- to get out of their air conditioned Toyota Landcruisers and both fund and use public tran A 20-year-old recently became internet famous for punching a man who joked about raping a drunk girl on the street one night. When is it ethical--and more importantly, efficient-- for individuals to take justice into their own hands? This question is particularly salient in Ghana, where vigilante justice is a common response to crime, and that justics goes up to and includes death for perpetrators of rape or severe property crime.  Actually, I did see what you did there. And I have a machete. Justice generally serves two economic purposes: to make an injured party whole, and to provide a disincentive against bad behavior. Vigilante justice tends to be focused on the latter. If you doubt this, just wait for the next Batman movie-- I guarantee my dear Bruce Wayne will wreak more economic havoc as the caped crusader than he will provide in redress. Vigilante justice comes at a high price, to the executioner, society, and to innocent parties who fall mistakenly fall victim to it, and is limited in the benefits it can provide.

In order to be justified then, vigilante justice must have a very high deterrent benefit. This will generally only be the case when legal justice systems completely fail to act as deterrents to morally reprehensible acts. It seems to me that the woman's decision to punch the rape joker fits this criteria. No court in the United States would ever provide any kind of consequence for comments like this man made. To me, the welfare gain from the chilling effect (amplified by publicity) this will have on such jokes, which quickly turn a fun night out into a stomah-clenching affair that can haunt a woman for months (if not years), clearly outweigh one guy having a sore nose for a couple weeks. Similarly, in Ghana, legal remedies are a poor deterrent to crime. (Especially legal remedies that are actually legal, NOT including police beating suspsects.) Even in clear cases where suspects are caught red-handed with eyewitnesses present, criminals often walk free. Two friends of mine were beaten with bricks a couple years ago, and one of the assailants was captured at the scene of the crime, but was released after several months of courtroom circus. Death by beating, however horrific, not only provides a clear disincentive to crime but permanently removes a criminal from society. So can vigilante justice be morally and efficiently right? Yes. Does that mean it should go unpunished? No. The fact that vigilante justice can have a high cost for falsely accused victims means that executioners must have a disincentive to engage in vigilante justice unless they are sure of its benefitcs. Punishing, or potentially punishing, perpetrators of vigilante justice provides that disincentive. So the woman who punched the joker should be potentially liable for damages, and those who engage in mob justice beyond that necessary for defense should be liable under assault laws, to prevent vigilantes from risking targeting those not truly guilty. This may seem like a rather extreme position; it is certainly influenced by living in situations where law enforcement seems ineffectual. However, the truth is, society engages in vigilante justice all the time. In the U.S., however, it is usually psychological, not physical: when someone cuts in line, they are often shamed, but not punched. Vigilante justice is an appropriate response to those inevitable situations where the law has no reach, but how it is exercised must be limited by disincentives against its most extreme forms. Last Saturday night around midnight, I was standing in the middle of a street in Tamale, trying in vain to beg or bribe a taxi driver to stop and take a dying man to the hospital. I hadn’t seen the motorcycle collision that injured this man and one other, but the small crowd, the battered bikes, and the bloody, limp bodies told the story clearly. My makeup, blond hair (combed for once), and red dress, which correctly marked me as a foreigner on my way to a dance club—normally very desirable fare for a taxi—suddenly carried little cachet. As multiple taxis turned me down, two of the man’s friends began a futile and possibly fatal attempt to load him onto the back of the motorcycle. His neck and limbs flopped sickeningly as the motorcycle sparked to life and died repeatedly.

In the end, the only way we could convince a driver to take the man to the hospital was to have a white person accompany him. A friend of mine drove ahead of the taxi on his own motorcycle, carrying one of the man’s friends. We paid the driver four times the going rate. As they drove away, a woman watching the scene remarked to me, “Of course the taxi driver can’t take the man. When he gets to the hospital, they will hold him responsible and make him pay if the man can’t.” Welcome to a world where individuals have the liberty not to have health coverage, and face the consequences for how they exercise that liberty. In Ghana, you don’t get treatment—sometimes even life-saving treatment—until you prove you can pay for it. Doctors will sit and watch you bleed while your friends and family cobble together money for payment, or rush to renew your health insurance policy. I once saw a four-year-old boy delivered to a rural health clinic after he ran onto the highway and was hit by a motorcycle. There was nothing the clinic could have done to save him. His mother spent his last moments not by his side, but running desperately through the village to get his insurance card. The issue of allowing indigent or liquidity-constrained individuals (those who could pay back their medical bills over time) to die aside, the serious economic issue here is that when the default assumption is that people cannot pay for health care, there are negative externalities that mean even those who can pay for care may not get it promptly, and as a result, may have worse outcomes. A man with thousands of cedis in his account should be able to get a taxi to the hospital; he should not be left on the road because the drivers fear he will be turned away on the hospital steps. A child with insurance should be treated promptly; he should not be left bleeding on a clinic table while his mother runs for proof of insurance. Those who support universal health care, or an insurance mandate, should not fail to recognize the costs, in terms of our government budget deficit, burden on the poor, and loss of economic freedom. However, those who are opposed to it should recognize the full costs of that liberty as well. One day at the Tamale office meeting:

Boss: “Okay, so who wants to join the monkey feeding committee?” Abu, whispering to me and Salifu: “I want to join the hongin committee.” Me: “The what?” Salifu: “You know, hongin. Hongin out.” He writes: “hanging” Me: “Oh! Americans say hAAAAAAngeen.” Salifu and Abu vainly try to suppress their snickers, and the boss glares at us. Ghana’s official language is English, and most people here speak it well. As in other English-speaking countries, however, the English spoken in Ghana doesn’t sound the same as what you hear in America. Newly-arrived Americans often struggle to understand, and be understood by, Ghanaians. To aid understanding, ex-pats often adjust the way they speak, trying to adopt Ghanaian vocabulary and accent. Are ex-pat attempts to speak “Ghanaian English” offensive? It can be nearly impossible to get around without it. As one of my ex-pat friends said, “You do what you have to do to be understood.” On the other hand, trying to emulate another accent almost always has awkward results. I cringe at the thought of trying to copy a British, Australian, or Southern accent, and would be truly annoyed if someone insisted in speaking to me Sarah Palin-style. Trying to change your accent can imply that the person you are speaking to is not sophisticated enough to understand other English accents. Several of my friends have been criticized for using Ghanaian accents in the workplace, on the grounds that it is condescending. I’ve had experiences in both directions. I’ve discovered that I will never be able to access money unless I direct taxis to the “bonk”, rather than the “baaaank”. But I’ve also been mortified when making a call to a Ghanaian, introducing myself with a slight Ghanaian accent, only to have the person respond in perfect BBC British English. I conducted an informal survey of the Ghanaians I work with, to see what they thought about ex-pats adopting Ghanaian accents and words. Here’s a sample of the responses: “You should try to make your words more clear for us.“ “It’s exciting and not offensive.” “Sometimes, when you try to pronounce it like we do, it sounds mocking.” “People expect you to try to change your accent. It’s helpful. “ “For those who are well-educated, they may feel like you are talking down to them.” “When expats try to speak pidgin, it’s funny.” “You should start normal, then if they don’t understand, then you can say it with the accent.” “When you go out in the community, it marks you as someone who has been here a while.” “When she speaks [without the accent], the guy is always turning to me and asking, ‘what did she say?’” “You don’t use ‘aba!’ right.” The Ghanaians I spoke to, all in our Northern office, had a range of education levels and experience abroad. They generally agreed that it’s not offensive when ex-pats try to speak in a Ghanaian accent. However, a couple of them noted that when a person does it in a mocking way, or uses a very severe accent with a highly educated person, it can be offensive. All of them thought that it was fine for ex-pats to adopt Ghanaian vocabulary, such as “small small”, “somehow”, or “this thing”. In fact, most said they don’t notice it as being different from our normal vocabulary. Learning local languages or even pidgin was universally lauded, although I was advised not to use pidgin in partner meetings. My conclusion, based on these responses and my own experiences, is that the idea that trying to copy a Ghanaian accent is offensive is overblown, at least here in the North. An honest effort to adapt your speech to make yourself better understood is often helpful, and at worst, will make you sound a little strange. One caveat might be using a particularly dramatic accent in a work setting, as some may see the implication that they can’t understand an American accent as an implication that they are not educated. Some tips for Americans speaking to Ghanaians in work settings: 1. Start by telling the people you are talking to that they should let you know if you are speaking too quickly, or if there is anything they don’t understand. 2. Speak slowly. 3. Enunciate your words. 4. Don’t try to copy exactly how Ghanaians say every word, just those necessary in order for them to understand. For example, you don’t need to say “wah-tah” to ask for water. Go ahead and say “waa-terrr “, in all it's nasal glory. 5. Pay attention to how you talk to people. It’s easy to get in the habit of talking one way to taxi drivers, and carry that into other conversations, where it is less appropriate. Talking in a Ghanaian accent won’t actually help that Australian guy understand you any better. Surveyors in our organization have coined the phrase "IPA reduction" to refer to the weight loss that commonly occurs among staff at all levels during and IPA survey.

I recently received a spam comment on one of my old blog posts: "I want to reduce my fats and gain my physique back. so i like the tips you have shared here." The post was about how to survey people about their perceived risk of getting sick, but anyway.... In honor of all spammers who want to reduce their fats, here are the secrets of the IPA reduction: 1. Always be sure to be deep in the bush during lunch time, so you can't eat. 2. Stay in places where the only thing you can buy to eat after 7pm is plain rice. 3. When you get tired of plain rice and crave vitamins, eat nothing but a head of cauliflower or 5 carrots raw for dinner. 4. Get malaria, food poisoning, or a parasite. Failing to wash your cauliflower and carrots will be conducive to this. 5. Spend lots of time walking around villages and pushing your moto out of mud and sand. 6. Stress out constantly. Work long hours so that you are too tired to eat. So that's the secret to the IPA Reduction. Of course, if someone comments that you have "reduced" here in Ghana, it's usually not a complement, and tips above are not actually advisable. (Except #5. Pushing your moto out of the mud is always advisable.) The good news is, the IPA Reduction can be avoided by taking the time and effort to plan to have healthy and satisfying food around even when doing field work. I have been staying at the hilariously-named Prison Guesthouse in Salaga, which triples as a restaurant and community center. Yesterday, the management warned me that there would be a "candidate jam" at the facility that evening.

Cool, I thought, some of the local candidates will be here to give speeches and then hang out and socialize while people listen to music and dance. Being a political nerd, I thought this sounded fascinating. What are small-town politics like in Salaga? My delusions were shattered when I asked one of my team members whether the candidates would be from NDC or NPP, and he informed me that they would be candidates for their junior secondary school level certifications. So yes, last night I had a middle school dance take place right outside my guesthouse window. After my purse was stolen in Burkina Faso, I called Wells Fargo to get my cards cancelled and order new ones. The hotel staff told me I could use the hotel front desk phone, since my phone was stolen and my money supply was limited.

I had to call two different lines to cancel and re-order my debit and credit cards. The debit card was fast to cancel, but they didn't offer the option of mailing the new card to me in Africa. The credit card was also quick to cancel, with one snag. When you first call the line for lost credit cards, the automated system asks for your credit card number. I didn't know it. The system gives no immediate option for this. I stayed on the line dumbly for several minutes before the automated voice informed me I could say "I don't know." Given that this is the line for lost cards, it seems like they should mention this sooner. I was able to cancel the card quickly, and the agent then mentioned i could have the card sent to an emergency address, for a cost of $50 for international mail. Considering the alternative of having no access to money, this seemed like a great deal. Then the trouble began. I was put on hold for extended periods, despite telling the agent I was calling from a country with no toll-free line. At some point, while on hold the hotel staff started yelling at me in French that I was taking too long on the phone. I struggled to explain in frazzled, broken french, that I was on hold. When I did get taken off hold, I was told that I would have to talk to a manager to get the card sent to a different address. On hold again, with the hotel concierge poking me with his pen. When I did talk to the manager, she told me that she was going to ask me some security questions, and if I didn't know the answers, that was okay, I could just say "I don't know" and she would ask another. She started with a couple I didn't know, and some I did. I didn't know my last card transaction amount-- it was a cash advance in cedis, and I didn't know the ATM fee or the exchange rate that would have applied. After I failed to give her the first eight base pairs of the DNA in my grandmother's 11th chromosome, she informed me that she couldn't change the mailing address because I failed to get enough of the questions right. I was livid. Why didn't she tell me this before? Why did she say it was "okay" to say "I don't know"? If I had known that I needed to get a certain percent correct, I could have looked up my last card transaction, or ordered a gene sequencing test. By now the hotel concierge was seriously skewering me with his pen, so I told the manager that I could not stay on the line but that I was very frustrated with how this call went. I hoped that the call was indeed being recorded to monitor quality. A week later, I called again. This time, when I mentioned that I was calling from abroad on a non-toll free line, I was directed to the collect line. I was able to get the card sent to the emergency address by answering one security question. I was put on hold, but I didn't mind, since Wells Fargo was paying for it. That is how a customer who is alone in a strange country and has just lost her access to funds should be treated. I don't know what went so terribly wrong the first time. I tried to write to Wells Fargo to tell them this story, and suggest that they change their automated call response; instruct agents to either not put international callers on hold, or give them the collect number; and inform people when failing a security question will result in not getting a needed service. It turns out, I also need to suggest that they allow more characters in their email contact form. So Wells Fargo, if you are reading this, that is why this is online for everyone to see instead of in your inbox. Also, dear concierge: I stole your pen and traded it to a small boy for a sticker of Qaddafi. For Easter weekend, I planned to drive my motorcycle to Ouagadougou from Tamale. It’s not a particularly long drive, perhaps 6 hours (my record is 10 hours on the road.) My plans were thwarted at the border, where I learned that to take the moto into Burkina, I needed the deed in order to prove that it wasn’t stolen. I had deliberately left the deed in Tamale to make sure I wouldn’t lose it.

The good news is that Burkina customs and border control officials never implied that I could get the moto in with a bribe. This was even more surprising, because I asked if I could bring it by paying for a license in Burkina, which, in retrospect, would have signaled that I was willing to pay a decent amount to get it in. I ended up leaving the motorcycle with the Ghana border control, who refused even a modest dash as a thank you. (I later heard a possible explanation for why the Ghana border police refused my dash—it was small peanuts to them. Allegedly, to get a post as a border patrol officer, you have to pay someone a dash on the order of GHC 1,500—but an official can make that much in a week from bribes from traders who want to avoid the even more onerous Ghana import taxes. Compared with that kind of money, a GHC 10 dash is worth forgoing in exchange for someone’s good opinion. ) I asked about leaving the moto with the Burkina border control. The officials there declined to keep it. However, the border head official tried to console me, saying, “Mais ca va—je veut dormir avec vous!” In English: “It’s okay—I want to sleep with you!” |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed