|

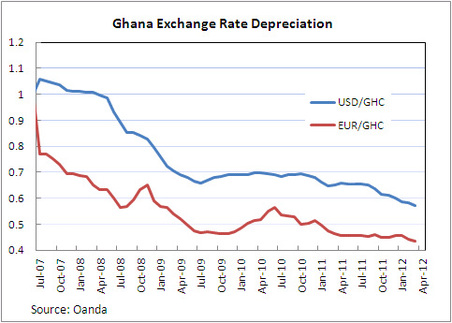

The Ghana Cedi has depreciated noticeably in recent months. Similar depreciations were seen in 2000 and 2008, which, like 2012 were election years. (In 2004, also an election year, the cedi did not depreciate much.)  By the way, the actual currency code for the Ghana cedi is GHS. GHC refers to the old cedi. International finance nerds love currency codes. Does the Ghana cedi experience election year blues? If so, why? To address this question, I examine a few alternative explanations for the depreciation of the cedi: 1. The cedi depreciates in election years due to uncertainty about Ghana’s political and economic future. Uncertainty could result in cedi depreciation if it leads investors to pull their money out of Ghana, or to hesitate to invest in the first place. With the lead-up to the election looking more tumultuous than previous elections, and recent unrest in other West African countries, it would seem investors have reason to be cautious. It’s hard to find data to test this theory right now, as foreign investment data usually come at a lag. Foreign investment was strong in 2011 compared with 2010, but that says little about developments in the last half year or so. Uncertainty could also lead to depreciation if the cedi falls under speculative attack. The Bank of Ghana has attributed some of the depreciation to speculation that drives down the value of the cedi. (http://www.bog.gov.gh/privatecontent/MPC_Press_Releases/50th_MPC_Press_release-_Final_Copy.pdf) 2. The cedi depreciates in election years due to politically-motivated expansionary monetary policy by the Bank of Ghana. The incumbent party would benefit from a strong economy come election time. Short-term economic growth can be encouraged through expansionary monetary and fiscal policies. Increasing the money supply, however, eventually leads to inflation, which hinders the economy. The Bank of Ghana has actually raised policy interest rates in recent months, but you can’t necessarily look at policy interest rates alone to see if monetary policy is expansionary. Here’s why: the government of Ghana has been spending a lot of money (typical of an election year.) Normally, this would push up the government’s borrowing costs, and raise interest rates generally. However, if the central bank keeps rates constant rather than letting them rise, this has an expansionary effect. A better measure to look at is inflation. One-year inflation rates appear to be pretty steady, but these do not reflect very recent trends. The trouble with looking at monthly inflation is that prices in Ghana are highly seasonal, rising in the spring and then falling after harvest, and seasonally adjusted series are not released. Inflation in January and February was only somewhat higher than inflation in those same months over the last few years. While the key statistics that would be indicative of expansionary monetary policy are inconclusive at this point, the Bank of Ghana does acknowledge some other indicators of looseness. The Bank mentions that credit has eased, meaning money is easier to get, and that starting in 2011, there have been signs of liquidity overhang—meaning that banks have more cash than they want, causing interest rates to fall. The Bank mentions that these lower interest rates on cedi assets could be driving investments to other currencies with a higher rate of return. 3. The cedi depreciation is only coincidental to the election year, and is driven by other factors, including global economic conditions. There are some other factors that could be driving cedi depreciation. The first, mentioned by the Bank of Ghana, is that the depreciation is driven by demand for foreign currency to buy imports. Despite strong exports of oil, gold and cocoa, Ghana’s imports are growing faster than exports. A second possibility is that economic trouble in Europe is having a negative impact on the funds that are available to go to Ghana. This could account for a decline in investment in Ghana, if indeed such a decline is occurring. Remittances, however, appear to have remained robust, according to the Bank of Ghana. So what do I think? I think it is possible the election is having an effect, either on foreign investment, or on speculation in the currency market. I also think that the Bank of Ghana’s policies, politically motivated or otherwise, are responsible for it. While political turmoil is hard to address, a central bank can easily punish speculators and attract investors by raising interest rates. It appears that the Bank of Ghana is now taking steps to do just that, but earlier action might have nipped the depreciation and any speculation in the bud. My guess is that growing imports and a stagnant global economy may play roles, but not central ones. The West African CFA Franc, for example, has actually risen against the dollar since the beginning of the year. This suggests that at least some of the cedi’s downward trend is specific to Ghana’s. Luckily, that means that Ghana has the power to change it.

2 Comments

I have been staying at the hilariously-named Prison Guesthouse in Salaga, which triples as a restaurant and community center. Yesterday, the management warned me that there would be a "candidate jam" at the facility that evening.

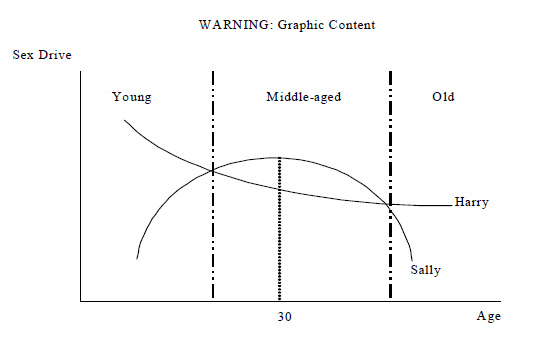

Cool, I thought, some of the local candidates will be here to give speeches and then hang out and socialize while people listen to music and dance. Being a political nerd, I thought this sounded fascinating. What are small-town politics like in Salaga? My delusions were shattered when I asked one of my team members whether the candidates would be from NDC or NPP, and he informed me that they would be candidates for their junior secondary school level certifications. So yes, last night I had a middle school dance take place right outside my guesthouse window. This is possibly the most awesome economics paper I have read in a while, containing the most awesome graph I have seen in a long time:

After my purse was stolen in Burkina Faso, I called Wells Fargo to get my cards cancelled and order new ones. The hotel staff told me I could use the hotel front desk phone, since my phone was stolen and my money supply was limited.

I had to call two different lines to cancel and re-order my debit and credit cards. The debit card was fast to cancel, but they didn't offer the option of mailing the new card to me in Africa. The credit card was also quick to cancel, with one snag. When you first call the line for lost credit cards, the automated system asks for your credit card number. I didn't know it. The system gives no immediate option for this. I stayed on the line dumbly for several minutes before the automated voice informed me I could say "I don't know." Given that this is the line for lost cards, it seems like they should mention this sooner. I was able to cancel the card quickly, and the agent then mentioned i could have the card sent to an emergency address, for a cost of $50 for international mail. Considering the alternative of having no access to money, this seemed like a great deal. Then the trouble began. I was put on hold for extended periods, despite telling the agent I was calling from a country with no toll-free line. At some point, while on hold the hotel staff started yelling at me in French that I was taking too long on the phone. I struggled to explain in frazzled, broken french, that I was on hold. When I did get taken off hold, I was told that I would have to talk to a manager to get the card sent to a different address. On hold again, with the hotel concierge poking me with his pen. When I did talk to the manager, she told me that she was going to ask me some security questions, and if I didn't know the answers, that was okay, I could just say "I don't know" and she would ask another. She started with a couple I didn't know, and some I did. I didn't know my last card transaction amount-- it was a cash advance in cedis, and I didn't know the ATM fee or the exchange rate that would have applied. After I failed to give her the first eight base pairs of the DNA in my grandmother's 11th chromosome, she informed me that she couldn't change the mailing address because I failed to get enough of the questions right. I was livid. Why didn't she tell me this before? Why did she say it was "okay" to say "I don't know"? If I had known that I needed to get a certain percent correct, I could have looked up my last card transaction, or ordered a gene sequencing test. By now the hotel concierge was seriously skewering me with his pen, so I told the manager that I could not stay on the line but that I was very frustrated with how this call went. I hoped that the call was indeed being recorded to monitor quality. A week later, I called again. This time, when I mentioned that I was calling from abroad on a non-toll free line, I was directed to the collect line. I was able to get the card sent to the emergency address by answering one security question. I was put on hold, but I didn't mind, since Wells Fargo was paying for it. That is how a customer who is alone in a strange country and has just lost her access to funds should be treated. I don't know what went so terribly wrong the first time. I tried to write to Wells Fargo to tell them this story, and suggest that they change their automated call response; instruct agents to either not put international callers on hold, or give them the collect number; and inform people when failing a security question will result in not getting a needed service. It turns out, I also need to suggest that they allow more characters in their email contact form. So Wells Fargo, if you are reading this, that is why this is online for everyone to see instead of in your inbox. Also, dear concierge: I stole your pen and traded it to a small boy for a sticker of Qaddafi. I’m a bit late responding to the whole DNC something Hilary Rosen’s statement that stay-at-home-mom Ann Romney “never worked a day in her life.” While I understand that Rosen intended the statement to be a reference to Ann Romney’s socio-economic status, the statement was insulting to moms who work hard raising their children and managing their household.

Let’s be clear: denigrating the works it takes to raise a family and manage a household is not feminist—nor does it do anything to help mothers who work outside of the home. Feminism is about making sure that men and women have the same opportunities. Those opportunities should include taking care of a family. Discounting the value—and difficulty—of work in the home doesn’t do anything to encourage policies that let working parents balance their work and home responsibilities. Discounting the value of work in the home doesn’t do anything to encourage men to take on more of the work raising families. The debate about stay-at-home-moms versus working moms is meaningless. Raising a family is difficult, whether you are working for a paycheck to support the family, working in the home, or both, and the main factor that determines how difficult it is is economic opportunity. What matters, assuming we think the family is an important aspect of our society, is getting people to place greater value on the work it takes to manage a family, and pursue policies that lessen that burden. I think Michelle Obama said it best with this tweet: “Every mother works hard, and every woman deserves to be respected.” For Easter weekend, I planned to drive my motorcycle to Ouagadougou from Tamale. It’s not a particularly long drive, perhaps 6 hours (my record is 10 hours on the road.) My plans were thwarted at the border, where I learned that to take the moto into Burkina, I needed the deed in order to prove that it wasn’t stolen. I had deliberately left the deed in Tamale to make sure I wouldn’t lose it.

The good news is that Burkina customs and border control officials never implied that I could get the moto in with a bribe. This was even more surprising, because I asked if I could bring it by paying for a license in Burkina, which, in retrospect, would have signaled that I was willing to pay a decent amount to get it in. I ended up leaving the motorcycle with the Ghana border control, who refused even a modest dash as a thank you. (I later heard a possible explanation for why the Ghana border police refused my dash—it was small peanuts to them. Allegedly, to get a post as a border patrol officer, you have to pay someone a dash on the order of GHC 1,500—but an official can make that much in a week from bribes from traders who want to avoid the even more onerous Ghana import taxes. Compared with that kind of money, a GHC 10 dash is worth forgoing in exchange for someone’s good opinion. ) I asked about leaving the moto with the Burkina border control. The officials there declined to keep it. However, the border head official tried to console me, saying, “Mais ca va—je veut dormir avec vous!” In English: “It’s okay—I want to sleep with you!”  This picture shows a sign in Burkina Faso warning against the harm to roads and vehicles from overloading, along side an example of a not-overloaded truck. Burkina seems to be more efficient about actually building their roads than Ghana. A year ago when I visited Ouagadougou, the road there was completely under construction. This time, from the border to Ouaga was all beautiful, new road. It's been two years and counting, and Ghana has no progress to show for the work they have been doing between Accra and Kumasi, the two largest cities in the country. To be honest, though, I think the real reason that Burkina's roads are better than Ghana's is that no matter how much you overload a donkey cart, it won't do much to the road. My last night in Ouagadougou, I enjoyed a lovely Vietnamese dinner, then went to the street to find a taxi to my hotel. It wasn’t late, but it was just starting to rain, and taxis were scarce, so I started walking in the direction of the hotel, knowing I would be more likely to find a taxi that way.

I was crossing an intersection when a man started yelling “La blanche! La blanche” (White! White!) I decided to ignore him, as this rude by any measure. The man then ran up behind me, and grabbed me around the neck with both arms. I had no idea what he was doing, so to be on the safe side, I screamed. I was able to duck out of his arms and push him away. He didn’t put up much resistance, so I decided this was just his idea of sport. I hit him across the face, then walked away, and he let me go. Hitting an assailant wasn’t the smartest thing—I probably should have taken off running—but I’m glad I did. What was he thinking? He didn’t strike me as being mentally ill in any way. The only conclusion that I can come to is that since I was clearly a foreigner, and because he thought I was physically weak, he felt like he could get away behavior that would be unacceptable in his own community. The more disturbing thing is that, even though there were half a dozen people in the immediate vicinity, no one did anything. No one tried to help, or even asked if I was okay. This was shocking to me, especially because in Ghana, people would have come running from all around. I’m not sure why no one helped—if it was because it was beginning to rain and they wanted to go home, or if it was because I was a foreigner, or if that’s just the culture in Ouagadougou. If you are reading this and thinking, “Poor Liz—what a god-awful country!”, then I have news for you: men do stuff like this to women all the time in the United States, and they get away with it. Ask any young woman living in a city like New York or DC when the last time was that she was catcalled on the street, or grabbed in a bar or club. Ask her if anyone said anything to the person who did it. The fact is, wherever conditions exist that allow people to harass others without consequence, there will be people who take advantage of that. I think there are two cultural tendencies that contribute to those conditions: 1. A general tendency not to get involved. This is something that you see a lot more in the west than in places like Ghana, where society values individualism less and communities are tightly-knit, creating more incentive to enforce good behavior. But everywhere, to some extent, people are often hesitant to get involved, either because of fear, or because of inconvenience. The result is that bad behavior goes unpunished. This is especially consequential in places where formal law and order is lacking. 2. In-group bias. I think that everywhere, people who are “different” are more likely to be targeted and less likely to be helped. (They are probably more likely to be targeted BECAUSE they are less likely to be helped.) These people might be vulnerable because they don’t speak the local language, and don’t have local social connections or social standing, but I think there is also a tendency for people who are different to be more objectified—they are seen first as “a white” or “a black”, rather than as another person. People have less problem with them being objects for others’ amusement, and they are less concerned with their welfare than they would be someone who appears to be from their same community. There are people who would argue that in-group bias is okay or even good, and that it encourages social cohesion. I argue that the cost of in-group bias is that the most vulnerable people are ignored when they need help. So if you don’t like what happened to me, I urge you to do two things. First, make yourself more of a “social enforcer.” Being a social enforcer can be intimidating. Natural social enforcers often have a high tolerance for stress. But generally, a person who enforces good social behavior, for example by chiding someone who cuts in line, are viewed favorably by everyone who observes the interaction. Second, try to fight your own in-group bias, and make an effort to reach out to those people who seem especially out of place. If they look out of place, they probably feel that way even more so. Treat them the way you would want your mother, or your sister, or your daughter treated if she were alone someplace strange. Interestingly, the two things I am encouraging—social enforcement and reducing in-group bias—are typically associated with opposite sides of the political and social spectrum. Social enforcement tends to be associated with conventional, authoritarian, and duty-oriented attitudes. Reduced in-group bias tends to be associated with liberal, individualistic, and intellectually-oriented attitudes. I don’t think this is an accident: all of these values are good; that’s why there are people that value them. If we all ascribe to each other’s values a little more—if social enforcers can apply their protections to a wider group of people, and if those who care about people who are different can make themselves into social enforcers—I think we would do better at protecting the most vulnerable from those people who have no values at all. You should not ever experience the Kintampo Police Escort Caravan. It only happens in deep night, and long-distance travel at night is generally unadvisable. I shouldn’t have had to experience it either, but because of a series of inconveniences, beginning with a driver and ticket seller lying to me about the destination of the car I bought a ticket for, my travel took about 10 hours longer than expected. The experience of the Kintampo Police Escort Caravan begins with waking up to find that your bus (or in my case, trotro) has stopped at the side of the road in the middle of the bush, in Kintampo—the district in Ghana most notorious for armed robberies on the road. The first-timers wonder why we are making sitting ducks of ourselves, before noticing the other vehicles also pulled over. The veterans hop out to buy jollof rice and jugs of palm oil from the vendors capitalizing on the situation.  The Kintampo Road, 2am After waiting 30 minutes to an hour, the police arrive with the caravan coming from the other direction. Everyone scrabbles to load back into their cars. Everyone starts off, and the ensuing scene looks less like an orderly security convoy than it does Mario Kart: with traffic going one direction, the cars drive all over the road, the faster ones overtaking the slower. The impression is only strengthened by the peppy hiplife music emanating from the trotros. As an overloaded trotro hit bumps in the road, it would not be that farfetched to imagine plantains flying off its roof and landing in the path of an NGO truck driven by Yoshi, causing it to go into a cartoonish tailspin. The police leave the cars to travel through Kintampo township on their own. Once on the other side of Kintampo, the bus, trucks, trotros and cars gather to wait for a second escort. I have never heard of a car being robbed while in the convoy. The convoy also likely increases safety be reducing the risk of head-on collisions at night, since traffic only moves one way at a time. It adds about 2 hours to the 5 hour drive, though. By the end of the night, I was very familiar with the Dagbani phrase “Ti chema!”—“Let’s go!”

The heavily-fortified Ivory Coast border Some of my respondents are in Ivory Coast. They end up in our sample because they have visited health facilities in Ghana. Why do Ivoirians come to Ghana for health care? Ghana has a very affordable national health insurance program. It’s not easy in rural areas to verify who lives where, so Ivorians in border areas occasionally sign up for health insurance, reporting that they live in a village on the Ghanaian side. Sometime they even give a typically-Ghanaian name, in place of their French-ier real one. This is bad for Ghana’s government budget, but it’s bad for us too, because it means that we are trying to find respondents with fake names, and we don’t even know what village they come from. Our typical strategy is to go to the handful of villages near the border, ask for anyone who might have visited the Ghanaian health facility, and see if they are the person we are looking for. You can imagine, when we walk in and essentially ask “So anyone around here defrauding Ghana Health Services?”, how many people yell “Me, me!” Surprisingly, though, we actually find people. I spent one day serving as moto driver for one of my surveyors, Nana, in the border area. The road was rough—in many places impassable by car—and the surveyor had never been on a moto in his life. When we first arrived at the health facility, still in Ghana, I asked the surveyor how far it was to the border, expecting it to be maybe a mile or two. He pointed to a spot two meters to my left. We crossed into Ivory Coast about three times that day. Most of the borders weren’t even marked. There was one border crossing where a couple of Ivoirian border police were playing cards. They were happy to give us directions to the Ivorian village we wanted to visit. Once across the border, not much changed, except that people in rural villages spoke French the same way they speak English in Ghana—that is to say, not much. I was able to communicate more with my tiny bit of Twi than with my more extensive (if badly pronounced) French vocabulary. Nana, fluent in Twi, was fine. The day ended with several unfruitful hours looking for “Sabrina”. I felt pretty good though. On the drive home, I smugly told Nana that there were not too many PAs in IPA who would have driven these roads and asked for directions in French and Twi. He winced and rubbed his seat as we hit a bump, and I am pretty sure he wished he had been with one of those other PAs. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed