|

A major study was recently found to contain an error that led the study to overestimate the cost-effectiveness of deworming by a factor of 100. (Note that this was NOT the IPA RCT study of deworming in Kenya, which found deworming to be highly cost-effective in part due to large positive spillover effects.)

This is the type of thing that keeps project associates up at night-- when we aren't staying up trying to track the surveys that came in that day, writing .do files to analyze our data, or drafting reports containing our results. The fact that we work long hours, on tight schedules, sometimes while delirious with malaria doesn't help. My most recent report was 120 pages long, and based on what must be tens of thousands of lines of stata code. It's hard to believe there are zero errors in that code. So how I am going to sleep tonight? I know two sets of eyes have looked over the code used in the analysis. I've looked critically at the findings to see if they make sense, and if they are consistent with the rest of the data. We might not be able to catch everything (were there some observations I should have recoded for that question?) But hopefully we can catch the "factor of 100" errors. Also, I am really tired.

1 Comment

Gene Sperling, former Clinton economic adviser, deficit hawk, and current adviser to Treasury Secretary Tim Geitner, is tipped to be the next Chair of the National Economic Council, which coordinates economic policy for the White House.

If you Google images of Gene Sperling, you get...Gene Sperling and Shakira...Gene Sperling and Angelia Jolie...I'm not sure if this means the U.S. economy is saved or doomed. (Maybe it just means people are more interested in pictures of Shakira and Angelina than Gene Sperling.) I happen to like both women, finding them talented, beautiful and socially conscious. Hopefully good taste in celebrities translates into good taste in economic policy. A friend sent me this blog entry from Createquity, a blog about arts in society that occasionally dabbles in critiquing the field of economics. The entry makes the case that economics is flawed in how it values welfare, and that economists don’t care about poor people.

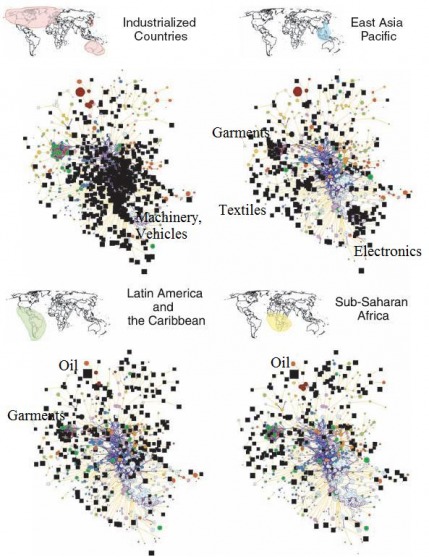

I generally agree that economics does not value welfare perfectly—as, I would guess, many economists would as well. A basic tenant of economics is that we can’t directly measure utility (I covered this in my intro to econ class, anyway). We know there are some rules that define the relationship between utility and the price we are willing to pay for things. For example, if a person is willing to pay more for an apple than an orange, we assume the apple had greater utility to that person than the orange. So we use the amount that people are willing to pay for things as an imperfect proxy for utility. As this relates to poverty, economists do know there are declining returns to income/consumption. Imagine you give a child $1, and she buys a doll. You give her another $1, and she buys candy. Since she chose to buy the doll first, she must value the doll more than the candy, so the first $1 was of greater value to her than the second $1. The difference in those values will be starker when comparing the first $1 of income that a person spends on food or shelter to the millionth $1 of income that the person spends on a designer purse. While we can recognize these things in individual situations, it is very hard to account for them more broadly. The author compares a poor consumer to a rich consumer who are both competing for an auction item. While the author’s example contains some problematic details (for example, the rich consumer thinks the item is something else, which is an example of a widely recognized market failure: imperfect information), the main problem with the example is that while the author can assert the poor consumer values the item more, in real life, this can be difficult to ascertain. In some cases it is clear—a starving poor person must value a sandwich more than a person who just ate a seven course meal. But how do you know who values a flat screen TV more? Just because that guy who lives in his parents’ basement says there is no way a millionaire could value a TV more than he does doesn’t mean it’s true. Attempting to assign more utility to the same dollar value creates problems. Measuring welfare differently for each consumer ignores the supplier. While selling a flat screen TV to the basement boy for $50 instead of to the millionaire for $5000 might result in more welfare for the consumer, what about the supplier who just lost $4950? To the supplier, $1 is $1, whether it comes from basement boy or the millionaire. Even if the welfare gain to the consumer is enough to outweigh what the supplier lost, there are also incentives to consider. Economics often has to make trade-offs between what is immediately welfare maximizing and incentives. Using dollars to measure welfare gives people incentive to produce things that are valuable to other members of society. Society doesn’t value basement boy’s couch-warming service. It does value whatever good or service the millionaire (or his grandfather) provided. When we use dollars to measure values, we are measuring in units of value to society as a whole, not to individuals. In some cases, trying to take some of these effects into account may make sense. Imagine trying to measure GDP, taking declining returns to income. One could argue that that would be a useful measurement, as it might capture welfare gains from using what we produce more equitably. Instead of just estimating the market price of every good and service produced in the economy (quite a task in itself), we’d have to track who consumed each good and service, then try to figure out where that spending ranked on that consumer’s priority list. Have fun doing this for exports!! None of these points are intended to refute the argument that welfare is imperfectly accounted for in economics. They are merely intended to explain why economics measures welfare in a way that can seem callous: it’s the best we’ve come up with so far. In addition to the fact that economics cannot perfectly capture welfare, there are things that economics cannot capture at all: morals. Economists can tell us the cost of providing food stamps, subsidized housing, or free education; we as a society must decide if we think that cost is enough to justify allowing some of our population to have inadequate food, shelter, or education. Economists can tell us the costs of measures to protect endangered species; we must decide if those costs outweigh the costs of losing one of earth’s creations forever. Economists can tell you the economic benefits of legal abortion; we must decide if aborting an embryo is wrong. Economists believe that we should make informed decisions, and try to provide as much information as possible about the economic costs and benefits of each alternative. It may or may not be true that economists value helping poor people less than the average citizen (however, I would note that economists who vote Democratic outnumber those who vote Republican by 2.5 to 1, suggesting that economists support social safety net programs as a rate higher than the general population). But if society decides that helping poor people is not worth the costs estimated by economists, then perhaps society needs to look critically not only at economics, but its own values. This paper isn't new, but I recently saw Ricardo Hausman give a presentation on it, and it is quite interesting. The basic premise is that the products that countries produce can be grouped according to the inputs required to produce those products. Knowing how products related to each other could help developing economies figure out what industries to focus on. It is easier to develop industries that share production inputs with products you are already making than it is to develop industries that require a completely new set of production inputs: it is easier for monkeys to swing to a nearby tree than it is for them to swing to a farther tree. The researchers used product categories and job categories to figure out how closely different products were related to each other in terms of inputs. They then looked at several sets of countries, and mapped which products they were producing. The diagrams above show the result of this exercise: the colored dots are products, the lines connect those products that share inputs, and the black squares show what each group of countries is producing. Developed economies produce goods near the center of the cluster. The goods on that part of the map are things like electronics, that require a lot of inputs, but share inputs with a lot of other products. Developing economies are at the periphery of the map, making goods with fewer inputs, and that don't share inputs with many other goods. The point: developing economies are less diversified (no surprise) and less flexible if their main product goes bust.

I've added labels describing important product clusters for each group of countries. Developed economies are clustered around high-value, complex product manufacturing. Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa both have oil as an important product. Asia has clusters in the areas garments, textiles, and electronics. This point about garments and textiles is interesting. Although it might seem obvious these should go together, they actually don't share many inputs. It's possible that the inputs, though not shared, have similar attributes. Perhaps they require workers with similar levels of education, even if the jobs those workers do are quite different. Or perhaps proximity matters: maybe it is cheaper to make fabric closer to where you sew it. Either way, it suggests targeting industries for development is even more complicated that the charts above suggest. According to NPR, this is the brainchild of Spike TV producer John Papola and libertarian economist Russel Roberts, together with rap duo Billy and Adam.

I’ve enjoyed seeing Tom Delay on Dancing with the Stars. While his

actual dancing has been awkward, he has made up for it with his humor. My favorite line from him? Tom’s dance instructor: “Now go left!” Tom: “It’s simply outrageous for me to go left!!” I think there should be more politicians on DWTS, and Newsweek agrees with me. They’ve published a list of 11 politicians they’d like to see on the show, including Janet Reno, Vladimir Putin, and Levi Johnston. In that spirit, DWTS should get some economists on. Here are some I’d like to see: · Jeffrey Sachs. Bono could perform for the results show. · Hank Paulson. Not technically an economist , I know, but maybe we could finally see him run like a bunny. · Stephen Levitt. I’m sure he’d come out of it with some research revealing fascinating insights into what it takes to win on the show. · Austan Goolsbee. I think he’d be a crowd-pleaser. Also, he might rub Len Goodman’s head. · Caroline Hoxby. She’s got an elegant look, and as a Rhodes Scholar, probably athletic aptitude. · Paul Krugman. Not going to happen, but one can dream. Other ideas? Share them in the comment section. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed