The Ghanaian communications regulator fined five Ghanaian telecom companies a total of 1.2 million GHC today for providing poor quality services, a move sure to be popular with pretty much everyone, since people in Ghana love their phones and hate all the phone companies. To give you an example of what poor services means, I haven't been able to call or text anyone on MTN, or receive calls, since I arrived in Sunyani yesterday-- and it was like that all over Brong Ahafo when I left last week. This isn't some village in the mountains-- Sunyani is a district capital. The fines were based on failure to provide coverage, geographically and temporally. The highest fine went to Airtel, which has actually provided pretty reliable services for my internet modem, including the hookup to write this article. In my opinion, the highest fine should have gone to Vodafone, for their atrocious service. Vodafone is the only provider of cable internet in Tamale, and has the only nice, reliable internet cafe. When home and business internet lines go down, they never come fix them, despite repeated calls requesting they do so. Why should they? They can keep charging the monthly rate, plus get additional income when people are forced to go to the internet cafe. This is why natural monopolies must be regulated.

4 Comments

Recently, in a small village print shop with an old copy machine discarded from Canada or Belgium or some such place, I received a printing bill for twice the amount I expected-- because I printed my document from a pen drive.

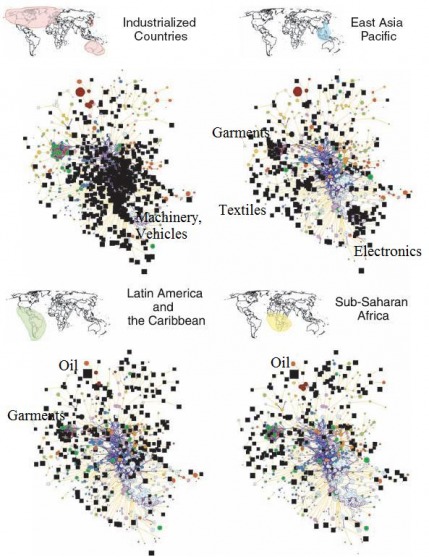

Newcomers to Ghana are often warned of the dangers of "promiscuous" pen drives. which can spread viruses. (The term seems increasingly appropriate the more I consider the mechanics of using a pen drive.) It is interesting to see that shops recognize the risk and tax it by charging higher rates on printing from pen drives. I was a bit put out, however, because the additional rate is charged per page, even though the virus risk is no different for printing a one-page document than a 100-page document. I'm looking forward to finding the shop that charges a flat rate fee for using a pen drive. I'll admit the deterrent is effective though: next time, I will email my document to myself. This paper isn't new, but I recently saw Ricardo Hausman give a presentation on it, and it is quite interesting. The basic premise is that the products that countries produce can be grouped according to the inputs required to produce those products. Knowing how products related to each other could help developing economies figure out what industries to focus on. It is easier to develop industries that share production inputs with products you are already making than it is to develop industries that require a completely new set of production inputs: it is easier for monkeys to swing to a nearby tree than it is for them to swing to a farther tree. The researchers used product categories and job categories to figure out how closely different products were related to each other in terms of inputs. They then looked at several sets of countries, and mapped which products they were producing. The diagrams above show the result of this exercise: the colored dots are products, the lines connect those products that share inputs, and the black squares show what each group of countries is producing. Developed economies produce goods near the center of the cluster. The goods on that part of the map are things like electronics, that require a lot of inputs, but share inputs with a lot of other products. Developing economies are at the periphery of the map, making goods with fewer inputs, and that don't share inputs with many other goods. The point: developing economies are less diversified (no surprise) and less flexible if their main product goes bust.

I've added labels describing important product clusters for each group of countries. Developed economies are clustered around high-value, complex product manufacturing. Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa both have oil as an important product. Asia has clusters in the areas garments, textiles, and electronics. This point about garments and textiles is interesting. Although it might seem obvious these should go together, they actually don't share many inputs. It's possible that the inputs, though not shared, have similar attributes. Perhaps they require workers with similar levels of education, even if the jobs those workers do are quite different. Or perhaps proximity matters: maybe it is cheaper to make fabric closer to where you sew it. Either way, it suggests targeting industries for development is even more complicated that the charts above suggest. This interesting story in the New York Times describes how cell phones are being used in rural Uganda to track banana diseases.

Africa has more mobile phones than it does land lines. This is very believable to me, as I saw for myself the proliferation of cell phones in Dakar, Senegal, in 2005. In urban Dakar, the primary draw of the cell phone seemed to be the cool factor, and the ability to talk to friends any time or place. (Senegalese youth really aren't that different from American teenagers, afterall.) At times it seemed bizarre however, to see people talking on cell phones who couldn't afford cars, school, medical care, or even -- in extreme cases -- sufficient food for their children. It is easy to jump to the conclusion that when people without electricity or clean water carry cell phones, this is a serious lack of spending priorities. An article about cell phone use among Washington DC's homeless prompted some similar sentiments among reader comments. However, both of these articles illustrate how cell phones can be a key tool for bringing real improvements to people's lives. The same wealthy Americans who view cell phones as luxuries have access to fast transportation, land lines, television, prolific bank branches, disposable cameras, iPods, and computers with internet. For the poor, both in the United States and in Africa, cell phones have the potential to give people access to news and other information, connect them to friends and relatives who live several days' walk away, allow them use modern banking, and let them enjoy music and entertainment that wealthy Americans take for granted. The newest generation of cell phones have most of the same basic functions as laptops, but cost much less, which could make them valuable in education. Cell phones can be tools at work too. In Dakar, I occasionally saw workers using cell phones to coordinate with their employers and fellow employees, to make the business more productive. Cell phones present a great opportunity to help a large number of low-income people in both developed and developing economies. Programs like the one mentioned in the NYT article, that teach people how to make the best use of cell phones' powerful capabilities, are right on target. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed