|

The New York Times reports that playing sports as a child has a positive impact on women's income when they are adults. More boys than girls play sports in high school; about one in three high school girls plays sports compared with half of high school boys. In an era when the majority of the population is overweight, this is one more reason why both girls and boys should be given opportunities and encouraged to participate in sports.

1 Comment

The Council of Economic Advisers has released the 2010 Economic Report of the President. You can find a link to the full report, as well as a summary of the highlights, here.

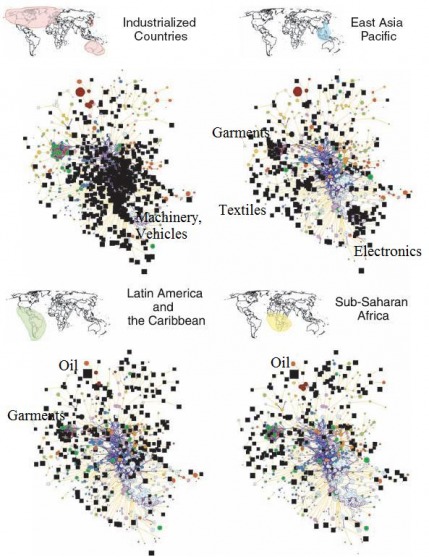

Quick summary: The economy was a mess when President Obama came into office, because of problems that were a long time in the making, including stagnating middle class incomes, rising health care costs, and flawed and under-regulated financial markets. The economy is still not great, with a slow recovery and lagging job formation expected, but it is in better shape than it would have been if the stimulus bills had not been implemented. We should still do more. Pass jobs support and health care reform now! This paper isn't new, but I recently saw Ricardo Hausman give a presentation on it, and it is quite interesting. The basic premise is that the products that countries produce can be grouped according to the inputs required to produce those products. Knowing how products related to each other could help developing economies figure out what industries to focus on. It is easier to develop industries that share production inputs with products you are already making than it is to develop industries that require a completely new set of production inputs: it is easier for monkeys to swing to a nearby tree than it is for them to swing to a farther tree. The researchers used product categories and job categories to figure out how closely different products were related to each other in terms of inputs. They then looked at several sets of countries, and mapped which products they were producing. The diagrams above show the result of this exercise: the colored dots are products, the lines connect those products that share inputs, and the black squares show what each group of countries is producing. Developed economies produce goods near the center of the cluster. The goods on that part of the map are things like electronics, that require a lot of inputs, but share inputs with a lot of other products. Developing economies are at the periphery of the map, making goods with fewer inputs, and that don't share inputs with many other goods. The point: developing economies are less diversified (no surprise) and less flexible if their main product goes bust.

I've added labels describing important product clusters for each group of countries. Developed economies are clustered around high-value, complex product manufacturing. Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa both have oil as an important product. Asia has clusters in the areas garments, textiles, and electronics. This point about garments and textiles is interesting. Although it might seem obvious these should go together, they actually don't share many inputs. It's possible that the inputs, though not shared, have similar attributes. Perhaps they require workers with similar levels of education, even if the jobs those workers do are quite different. Or perhaps proximity matters: maybe it is cheaper to make fabric closer to where you sew it. Either way, it suggests targeting industries for development is even more complicated that the charts above suggest. According to NPR, this is the brainchild of Spike TV producer John Papola and libertarian economist Russel Roberts, together with rap duo Billy and Adam.

The earthquake in Haiti has put a spotlight on international and interracial adoption, especially in light of the bizarre attempt by a church group to illegally transport children out of Haiti. In this article in Newsweek, the author airs a number of concerns she has about white families adopting children of other ethnicities from abroad.

Adopting a child, no matter where that child is from, presents unique challenges. The same is true for having a mixed-race family, whether that family is the result of adoption or of interracial marriage. The author is right in suggesting that people considering adoption should not take these issues lightly—and most don’t. However, I do take issue with the author’s concerns that white families who adopt children of other ethnicities are less able to celebrate that child’s culture, or that families looking to adopt would do better to adopt American children first. With regards to interracial adoption, it is again certainly true that interracial families face challenges that other families don’t. However, skin color is not necessarily the same as culture. A white child from Berlin does not have the same culture as a white ranch family in Montana; a Black Christian family in Virginia does not have the same culture as a Black Muslim child from West Africa. Both of these families would face the same challenge (or opportunity!) as a white family adopting a Haitian child in terms of learning about and celebrating their child’s culture. As to whether it is better to adopt at home or internationally, I can only say that all children need and deserve to have loving families and sufficient resources. It is a tragedy that not all children do have these things, regardless of where they are. When the author suggests that it would be better to adopt at home than from abroad, she falls into the exact mindset that she is critiquing—that adopting children are status symbols, signs of a parent’s virtue, and adopting children from the U.S. is of higher virtue than adopting from abroad. The fact is, for most parents, adoption is not about doing the most good. It is about growing a loving family, in a way that works for them. International adoption and interracial adoption are complicated issues, and opinions on them range widely—as do the backgrounds of those who express opinions. However, among the responses to these articles, I have seen few comments from people who have been in the position of being adopted by a family of another nationality and ethnicity. Because I believe that this perspective is important to informing how we think about this issue, I have asked Nicole Schultz to contribute a guest post on this issue. Nicole was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, placed in an orphanage by her biological father, and adopted by a white American family. Her post is below. If you have any questions about her experience, please post them in the comments and I will relay them to her. Who Am I?

I was born Marie-Nicole Clermont. However, after I was adopted from Haiti by white Americans, I was renamed. Nicole Schultz. Apparently their oldest daughter's middle name was Marie, therefore they took that away. Am I bitter about that? Hmm, yes a little bit. I never understood how her middle name had anything to do with my first name. Yeah, pretty much that whole fiasco never made a whole lot of sense to me. When I was in second grade, I got everyone including my teachers to call me Marie. Eventually, I just accepted that I was Nicole. Am I bitter that I probably will never get to see my biological family, or anyone biologically related to me? Yes, it is an ache that I constantly battle, something that will never go away. Did I grow up thinking it was strange that they were white and I wasn't? No. There never were racial barriers between my family and me. The only barriers were inflicted by the outside world: people thinking that white parents could never adopt someone from another race. Well, they're wrong, because I and thousands others are proof. The only thing that causes barriers with white people adopting children from other races are the people judging them, the ones who have no experience of the matter and insist on making damaging opinions regardless. In simple terms, they pass judgment on things they know not of. But if you were to ask me if I ever would take it back, the life I now live, for the life I once I lived in Haiti, the answer would be no. I wouldn't trade the world, the parents, and the family I have now. Sure, there are some struggles I face, that I wouldn't have had if I were an American adopted by another American. However, that is neither here nor there. I was put up for adoption by my biological father, because he wanted a better life for me. Who is it to deny him the opportunity to give his child a better life, when the opportunity is available?! My American parents adopted me out of love. They weren't crazed celebrities trying to add me as a good looking accessory to show off to their aristocratic society. Nor were they some religious fanatics trying to save my soul for judgment day. No, they were simple people, who wanted to have another child. Well, and that child was me. Nicole Kristine Schultz, born in Haiti, raised in America. And I am still ever bit 100% Haitian, and no one will ever be able to take that from me. -Nicole Schultz |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed