|

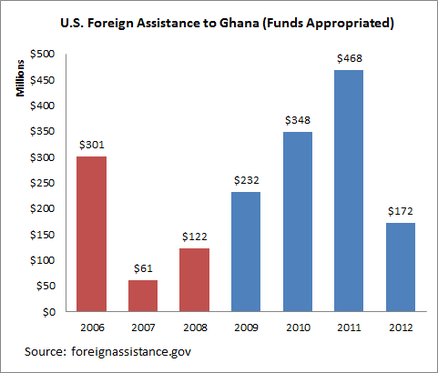

Not Ghanaians. Despite the fact that Obama is pretty much universally liked, Ghanaians don't really see themselves as having any real stake in the election. I asked five of my colleagues, all highly educated Ghanaians who could name both presidential contenders, if they cared who won. All five answered, a little hesitantly, "umm...not really." They didn't see any difference in the attention or assistance Africa received with Obama at the helm compared with Bush. What do the numbers say? Here is U.S. foreign assistance appropriations for Ghana from 2006 to 2012: (foreignassistance.gov only gives data back to 2006, and I couldn't get the numbers to match up with Census Bureau data, which go back farther but are less current. If anyone knows how to reconcile the series, I'd love to show data for the whole Bush administration.)

Aid appears to be higher during the Obama administration. (The Census data suggest annual foreign aid of under $100 million a year for the earlier years of the Bush administration.) But wait-- how much of the Obama spending is actually the result of the MCC compact signed under Bush? Although MCC spending isn't trivial-- $457 million for the period-- USAID spending is still much higher, and over half of the MCC appropriations were in 2006. By my reading, Ghana was better off, in terms of simple U.S. dollar aid receipts, under Obama.

3 Comments

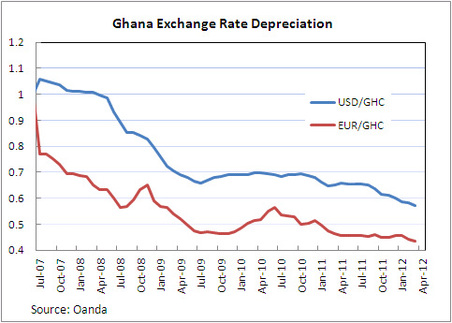

The Ghana Cedi has depreciated noticeably in recent months. Similar depreciations were seen in 2000 and 2008, which, like 2012 were election years. (In 2004, also an election year, the cedi did not depreciate much.)  By the way, the actual currency code for the Ghana cedi is GHS. GHC refers to the old cedi. International finance nerds love currency codes. Does the Ghana cedi experience election year blues? If so, why? To address this question, I examine a few alternative explanations for the depreciation of the cedi: 1. The cedi depreciates in election years due to uncertainty about Ghana’s political and economic future. Uncertainty could result in cedi depreciation if it leads investors to pull their money out of Ghana, or to hesitate to invest in the first place. With the lead-up to the election looking more tumultuous than previous elections, and recent unrest in other West African countries, it would seem investors have reason to be cautious. It’s hard to find data to test this theory right now, as foreign investment data usually come at a lag. Foreign investment was strong in 2011 compared with 2010, but that says little about developments in the last half year or so. Uncertainty could also lead to depreciation if the cedi falls under speculative attack. The Bank of Ghana has attributed some of the depreciation to speculation that drives down the value of the cedi. (http://www.bog.gov.gh/privatecontent/MPC_Press_Releases/50th_MPC_Press_release-_Final_Copy.pdf) 2. The cedi depreciates in election years due to politically-motivated expansionary monetary policy by the Bank of Ghana. The incumbent party would benefit from a strong economy come election time. Short-term economic growth can be encouraged through expansionary monetary and fiscal policies. Increasing the money supply, however, eventually leads to inflation, which hinders the economy. The Bank of Ghana has actually raised policy interest rates in recent months, but you can’t necessarily look at policy interest rates alone to see if monetary policy is expansionary. Here’s why: the government of Ghana has been spending a lot of money (typical of an election year.) Normally, this would push up the government’s borrowing costs, and raise interest rates generally. However, if the central bank keeps rates constant rather than letting them rise, this has an expansionary effect. A better measure to look at is inflation. One-year inflation rates appear to be pretty steady, but these do not reflect very recent trends. The trouble with looking at monthly inflation is that prices in Ghana are highly seasonal, rising in the spring and then falling after harvest, and seasonally adjusted series are not released. Inflation in January and February was only somewhat higher than inflation in those same months over the last few years. While the key statistics that would be indicative of expansionary monetary policy are inconclusive at this point, the Bank of Ghana does acknowledge some other indicators of looseness. The Bank mentions that credit has eased, meaning money is easier to get, and that starting in 2011, there have been signs of liquidity overhang—meaning that banks have more cash than they want, causing interest rates to fall. The Bank mentions that these lower interest rates on cedi assets could be driving investments to other currencies with a higher rate of return. 3. The cedi depreciation is only coincidental to the election year, and is driven by other factors, including global economic conditions. There are some other factors that could be driving cedi depreciation. The first, mentioned by the Bank of Ghana, is that the depreciation is driven by demand for foreign currency to buy imports. Despite strong exports of oil, gold and cocoa, Ghana’s imports are growing faster than exports. A second possibility is that economic trouble in Europe is having a negative impact on the funds that are available to go to Ghana. This could account for a decline in investment in Ghana, if indeed such a decline is occurring. Remittances, however, appear to have remained robust, according to the Bank of Ghana. So what do I think? I think it is possible the election is having an effect, either on foreign investment, or on speculation in the currency market. I also think that the Bank of Ghana’s policies, politically motivated or otherwise, are responsible for it. While political turmoil is hard to address, a central bank can easily punish speculators and attract investors by raising interest rates. It appears that the Bank of Ghana is now taking steps to do just that, but earlier action might have nipped the depreciation and any speculation in the bud. My guess is that growing imports and a stagnant global economy may play roles, but not central ones. The West African CFA Franc, for example, has actually risen against the dollar since the beginning of the year. This suggests that at least some of the cedi’s downward trend is specific to Ghana’s. Luckily, that means that Ghana has the power to change it. I have been staying at the hilariously-named Prison Guesthouse in Salaga, which triples as a restaurant and community center. Yesterday, the management warned me that there would be a "candidate jam" at the facility that evening.

Cool, I thought, some of the local candidates will be here to give speeches and then hang out and socialize while people listen to music and dance. Being a political nerd, I thought this sounded fascinating. What are small-town politics like in Salaga? My delusions were shattered when I asked one of my team members whether the candidates would be from NDC or NPP, and he informed me that they would be candidates for their junior secondary school level certifications. So yes, last night I had a middle school dance take place right outside my guesthouse window. I’m a bit late responding to the whole DNC something Hilary Rosen’s statement that stay-at-home-mom Ann Romney “never worked a day in her life.” While I understand that Rosen intended the statement to be a reference to Ann Romney’s socio-economic status, the statement was insulting to moms who work hard raising their children and managing their household.

Let’s be clear: denigrating the works it takes to raise a family and manage a household is not feminist—nor does it do anything to help mothers who work outside of the home. Feminism is about making sure that men and women have the same opportunities. Those opportunities should include taking care of a family. Discounting the value—and difficulty—of work in the home doesn’t do anything to encourage policies that let working parents balance their work and home responsibilities. Discounting the value of work in the home doesn’t do anything to encourage men to take on more of the work raising families. The debate about stay-at-home-moms versus working moms is meaningless. Raising a family is difficult, whether you are working for a paycheck to support the family, working in the home, or both, and the main factor that determines how difficult it is is economic opportunity. What matters, assuming we think the family is an important aspect of our society, is getting people to place greater value on the work it takes to manage a family, and pursue policies that lessen that burden. I think Michelle Obama said it best with this tweet: “Every mother works hard, and every woman deserves to be respected.” My last night in Ouagadougou, I enjoyed a lovely Vietnamese dinner, then went to the street to find a taxi to my hotel. It wasn’t late, but it was just starting to rain, and taxis were scarce, so I started walking in the direction of the hotel, knowing I would be more likely to find a taxi that way.

I was crossing an intersection when a man started yelling “La blanche! La blanche” (White! White!) I decided to ignore him, as this rude by any measure. The man then ran up behind me, and grabbed me around the neck with both arms. I had no idea what he was doing, so to be on the safe side, I screamed. I was able to duck out of his arms and push him away. He didn’t put up much resistance, so I decided this was just his idea of sport. I hit him across the face, then walked away, and he let me go. Hitting an assailant wasn’t the smartest thing—I probably should have taken off running—but I’m glad I did. What was he thinking? He didn’t strike me as being mentally ill in any way. The only conclusion that I can come to is that since I was clearly a foreigner, and because he thought I was physically weak, he felt like he could get away behavior that would be unacceptable in his own community. The more disturbing thing is that, even though there were half a dozen people in the immediate vicinity, no one did anything. No one tried to help, or even asked if I was okay. This was shocking to me, especially because in Ghana, people would have come running from all around. I’m not sure why no one helped—if it was because it was beginning to rain and they wanted to go home, or if it was because I was a foreigner, or if that’s just the culture in Ouagadougou. If you are reading this and thinking, “Poor Liz—what a god-awful country!”, then I have news for you: men do stuff like this to women all the time in the United States, and they get away with it. Ask any young woman living in a city like New York or DC when the last time was that she was catcalled on the street, or grabbed in a bar or club. Ask her if anyone said anything to the person who did it. The fact is, wherever conditions exist that allow people to harass others without consequence, there will be people who take advantage of that. I think there are two cultural tendencies that contribute to those conditions: 1. A general tendency not to get involved. This is something that you see a lot more in the west than in places like Ghana, where society values individualism less and communities are tightly-knit, creating more incentive to enforce good behavior. But everywhere, to some extent, people are often hesitant to get involved, either because of fear, or because of inconvenience. The result is that bad behavior goes unpunished. This is especially consequential in places where formal law and order is lacking. 2. In-group bias. I think that everywhere, people who are “different” are more likely to be targeted and less likely to be helped. (They are probably more likely to be targeted BECAUSE they are less likely to be helped.) These people might be vulnerable because they don’t speak the local language, and don’t have local social connections or social standing, but I think there is also a tendency for people who are different to be more objectified—they are seen first as “a white” or “a black”, rather than as another person. People have less problem with them being objects for others’ amusement, and they are less concerned with their welfare than they would be someone who appears to be from their same community. There are people who would argue that in-group bias is okay or even good, and that it encourages social cohesion. I argue that the cost of in-group bias is that the most vulnerable people are ignored when they need help. So if you don’t like what happened to me, I urge you to do two things. First, make yourself more of a “social enforcer.” Being a social enforcer can be intimidating. Natural social enforcers often have a high tolerance for stress. But generally, a person who enforces good social behavior, for example by chiding someone who cuts in line, are viewed favorably by everyone who observes the interaction. Second, try to fight your own in-group bias, and make an effort to reach out to those people who seem especially out of place. If they look out of place, they probably feel that way even more so. Treat them the way you would want your mother, or your sister, or your daughter treated if she were alone someplace strange. Interestingly, the two things I am encouraging—social enforcement and reducing in-group bias—are typically associated with opposite sides of the political and social spectrum. Social enforcement tends to be associated with conventional, authoritarian, and duty-oriented attitudes. Reduced in-group bias tends to be associated with liberal, individualistic, and intellectually-oriented attitudes. I don’t think this is an accident: all of these values are good; that’s why there are people that value them. If we all ascribe to each other’s values a little more—if social enforcers can apply their protections to a wider group of people, and if those who care about people who are different can make themselves into social enforcers—I think we would do better at protecting the most vulnerable from those people who have no values at all. In Ghana, large plastic bags, printed with plaid or otherdesigns, are prolific. The bags arecalled “Ghana Must Go” bags. I haveasked numerous Ghanaians why they are called this. They reply that Nigerians call them that, forunknown reasons. I finally learned thatthe name originates from Nigeria’s political turmoil in 1983, when manyGhanaians fled Nigeria. They hastilypacked their things in these bags.

Upon discovering these bags, I decided that they would be agood inexpensive option to carry our surveys, and dispatched the field managersto buy a couple for each of their offices. The tough field managers, who are a sophisticated combination of book-smartand street-smart, came back with bags printed with cartoon bears and cartoonpigs. Secretly amused, I asked themwhether they thought the print on the bags reflected the seriousness and professionalismof IPA. The next day a third bagappeared bearing cartoon Mickey Mouse. The bags held up during the course of the surveying,ferrying blank surveys to the field and completed surveys back to Tamale. StuffNigerianPeopleLike.com claims a GhanaMust Go can carry a child and his dog for miles. When I took our complete batch of surveys toAccra, the bags weighed in at 35 kilo per bag, which unfortunately, seems to bemore than a child-dog combo. My bags weredestroyed in one bus trip to Accra. To add injury to insult, plastic handles onthe bags chafed my palms, which have been peeling unattractively for weeksdespite copious amounts of shea butter. The surveys ultimately made it to the data team, whopolitely did not comment on the layers of dust the surveys had acquired duringtheir sojourn through the Northern Region. The lesson is that while I highly recommendGhana Must Gos for children, dogs, and objects with high volume-to-mass ratios,I do not recommend them for objects with density greater than or equal to adusty IPA survey.  Bush said, "I know the human being and fish can coexist peacefully." Obama said, "The Interior Department is in charge of salmon while they're in fresh water, but the Commerce Department handles them in when they're in saltwater. I hear it gets even more complicated once they're smoked." As a proud representative of the Pacific Northwest, I demand that my elected officials start taking my fish seriously!

Gene Sperling, former Clinton economic adviser, deficit hawk, and current adviser to Treasury Secretary Tim Geitner, is tipped to be the next Chair of the National Economic Council, which coordinates economic policy for the White House.

If you Google images of Gene Sperling, you get...Gene Sperling and Shakira...Gene Sperling and Angelia Jolie...I'm not sure if this means the U.S. economy is saved or doomed. (Maybe it just means people are more interested in pictures of Shakira and Angelina than Gene Sperling.) I happen to like both women, finding them talented, beautiful and socially conscious. Hopefully good taste in celebrities translates into good taste in economic policy. A friend sent me this blog entry from Createquity, a blog about arts in society that occasionally dabbles in critiquing the field of economics. The entry makes the case that economics is flawed in how it values welfare, and that economists don’t care about poor people.

I generally agree that economics does not value welfare perfectly—as, I would guess, many economists would as well. A basic tenant of economics is that we can’t directly measure utility (I covered this in my intro to econ class, anyway). We know there are some rules that define the relationship between utility and the price we are willing to pay for things. For example, if a person is willing to pay more for an apple than an orange, we assume the apple had greater utility to that person than the orange. So we use the amount that people are willing to pay for things as an imperfect proxy for utility. As this relates to poverty, economists do know there are declining returns to income/consumption. Imagine you give a child $1, and she buys a doll. You give her another $1, and she buys candy. Since she chose to buy the doll first, she must value the doll more than the candy, so the first $1 was of greater value to her than the second $1. The difference in those values will be starker when comparing the first $1 of income that a person spends on food or shelter to the millionth $1 of income that the person spends on a designer purse. While we can recognize these things in individual situations, it is very hard to account for them more broadly. The author compares a poor consumer to a rich consumer who are both competing for an auction item. While the author’s example contains some problematic details (for example, the rich consumer thinks the item is something else, which is an example of a widely recognized market failure: imperfect information), the main problem with the example is that while the author can assert the poor consumer values the item more, in real life, this can be difficult to ascertain. In some cases it is clear—a starving poor person must value a sandwich more than a person who just ate a seven course meal. But how do you know who values a flat screen TV more? Just because that guy who lives in his parents’ basement says there is no way a millionaire could value a TV more than he does doesn’t mean it’s true. Attempting to assign more utility to the same dollar value creates problems. Measuring welfare differently for each consumer ignores the supplier. While selling a flat screen TV to the basement boy for $50 instead of to the millionaire for $5000 might result in more welfare for the consumer, what about the supplier who just lost $4950? To the supplier, $1 is $1, whether it comes from basement boy or the millionaire. Even if the welfare gain to the consumer is enough to outweigh what the supplier lost, there are also incentives to consider. Economics often has to make trade-offs between what is immediately welfare maximizing and incentives. Using dollars to measure welfare gives people incentive to produce things that are valuable to other members of society. Society doesn’t value basement boy’s couch-warming service. It does value whatever good or service the millionaire (or his grandfather) provided. When we use dollars to measure values, we are measuring in units of value to society as a whole, not to individuals. In some cases, trying to take some of these effects into account may make sense. Imagine trying to measure GDP, taking declining returns to income. One could argue that that would be a useful measurement, as it might capture welfare gains from using what we produce more equitably. Instead of just estimating the market price of every good and service produced in the economy (quite a task in itself), we’d have to track who consumed each good and service, then try to figure out where that spending ranked on that consumer’s priority list. Have fun doing this for exports!! None of these points are intended to refute the argument that welfare is imperfectly accounted for in economics. They are merely intended to explain why economics measures welfare in a way that can seem callous: it’s the best we’ve come up with so far. In addition to the fact that economics cannot perfectly capture welfare, there are things that economics cannot capture at all: morals. Economists can tell us the cost of providing food stamps, subsidized housing, or free education; we as a society must decide if we think that cost is enough to justify allowing some of our population to have inadequate food, shelter, or education. Economists can tell us the costs of measures to protect endangered species; we must decide if those costs outweigh the costs of losing one of earth’s creations forever. Economists can tell you the economic benefits of legal abortion; we must decide if aborting an embryo is wrong. Economists believe that we should make informed decisions, and try to provide as much information as possible about the economic costs and benefits of each alternative. It may or may not be true that economists value helping poor people less than the average citizen (however, I would note that economists who vote Democratic outnumber those who vote Republican by 2.5 to 1, suggesting that economists support social safety net programs as a rate higher than the general population). But if society decides that helping poor people is not worth the costs estimated by economists, then perhaps society needs to look critically not only at economics, but its own values. In this clip, Oscar the Grouch's GNN (Grouchy News Network) just isn't grouchy enough, prompting viewers to switch to a "trashier" news show: Pox News.

Obviously the Obama administration is leaning on PBS. You can do your part to show PBS that this is unacceptable: don't buy any products from companies that advertise on their channel. Clearly I need to watch more Sesame Street. Happy 40th! |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed