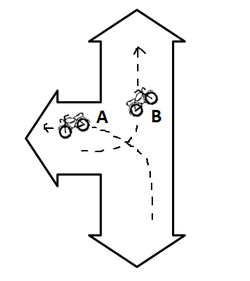

Tamale has a number of traffic norms that would make a driver's ed teacher turn to drink on the road. A classic example is the "Tamale turn", pictured at left. In Tamale, if you are making a left turn off of an arterial, and there is vehicle waiting to turn left ON to the arterial, rather than pass in front of the other vehicle, you pass behind them, while they simultaneously turn onto the arterial. One can see why drivers might think this makes sense. Both vehicles can turn at once, and if the arterial is busy, the vehicle waiting to turn on to it can take advantage of the other vehicle slowing down. But as traffic gets denser, the Tamale turn becomes more hazardous. If there are several vehicles waiting to turn on to the arterial, the vehicle turning off the arterial has to negotiate a route behind the turning vehicle, and in front of the waiting vehicles, who may not be on the lookout for a turning vehicle. And more vehicles in the intersection at once raises the risk of a collision as well. As Tamale's traffic worsens, many similar traffic norms, such as running red lights and passing on the right, technically illegal but general practice in Tamale, will become less efficient and more hazardous. But they will already be ingrained as the standard. What to do? Some ideas: 1. Give driver's licenses based on merit rather than bribes, to give drivers an incentive to learn the rules on the books. 2. Ticket drivers for practices that threaten public safety rather than focusing on trivial offenses easy to convert to payouts. Your additional ideas are welcome in the comments!

3 Comments

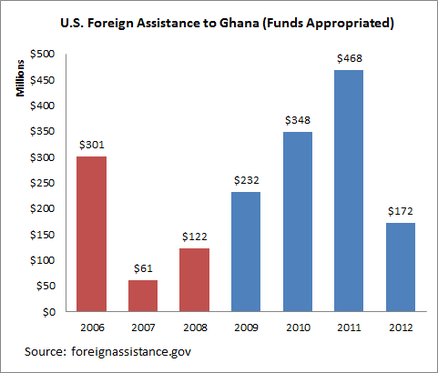

Not Ghanaians. Despite the fact that Obama is pretty much universally liked, Ghanaians don't really see themselves as having any real stake in the election. I asked five of my colleagues, all highly educated Ghanaians who could name both presidential contenders, if they cared who won. All five answered, a little hesitantly, "umm...not really." They didn't see any difference in the attention or assistance Africa received with Obama at the helm compared with Bush. What do the numbers say? Here is U.S. foreign assistance appropriations for Ghana from 2006 to 2012: (foreignassistance.gov only gives data back to 2006, and I couldn't get the numbers to match up with Census Bureau data, which go back farther but are less current. If anyone knows how to reconcile the series, I'd love to show data for the whole Bush administration.)

Aid appears to be higher during the Obama administration. (The Census data suggest annual foreign aid of under $100 million a year for the earlier years of the Bush administration.) But wait-- how much of the Obama spending is actually the result of the MCC compact signed under Bush? Although MCC spending isn't trivial-- $457 million for the period-- USAID spending is still much higher, and over half of the MCC appropriations were in 2006. By my reading, Ghana was better off, in terms of simple U.S. dollar aid receipts, under Obama.  "A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It's where the rich use public transportation." If the truth of this statement is not immediately apparent, you probably have never commuted in a West African city. Accra needs a lot of infrastructure improvements, but one thing it does not need are more cars. After work, I can run the two miles to my gym faster than I could take a taxi there. Traffic is similarly bad in Kumasi and Dakar, and is rapidly worsening in Tamale. Driving is no picnic in American cities, either. The difference? In American cities, rich people often choose to live in places accessible to public transportation, and their taxes and patronage support transit systems that benefit the rich and poor alike (even LA is getting on the bandwagon). In developing country cities, the poor take low quality public transit, such as trotros and shared taxis, while the rich clog the roads with their private cars and taxis. While roads in developing country cities could certainly be improved (I would love to see someone apply traffic light efficiency models to Accra traffic), the reality is there is limited capacity to expand current roads or build new ones in the middle of the city. Poor people are already taking public transport. That leaves one viable solution to traffic in developing country cities: getting rich people to convert to public transport. For practical and cultural reasons, this is an uphill battle. First, the main reason rich people use public transport in developed cities is not because they are altruistic, it is because it is faster and easier than driving. Accra currently has no public transit system that can rival the speed and efficiency of a private car. Considerable investment would have to be made in a rail or bus system with widespread coverage and efficiency in order to convince people to convert. Second, there is a cultural attachment to driving. Owning a car is a definitive status symbol in West Africa; taxi drivers are often confused when I, a person who apparently has the money to take a taxi, choose to walk. Improving traffic in Accra will require a commitment from the wealthy and elite-- both foreigners and Ghanaians-- to get out of their air conditioned Toyota Landcruisers and both fund and use public tran Last Saturday night around midnight, I was standing in the middle of a street in Tamale, trying in vain to beg or bribe a taxi driver to stop and take a dying man to the hospital. I hadn’t seen the motorcycle collision that injured this man and one other, but the small crowd, the battered bikes, and the bloody, limp bodies told the story clearly. My makeup, blond hair (combed for once), and red dress, which correctly marked me as a foreigner on my way to a dance club—normally very desirable fare for a taxi—suddenly carried little cachet. As multiple taxis turned me down, two of the man’s friends began a futile and possibly fatal attempt to load him onto the back of the motorcycle. His neck and limbs flopped sickeningly as the motorcycle sparked to life and died repeatedly.

In the end, the only way we could convince a driver to take the man to the hospital was to have a white person accompany him. A friend of mine drove ahead of the taxi on his own motorcycle, carrying one of the man’s friends. We paid the driver four times the going rate. As they drove away, a woman watching the scene remarked to me, “Of course the taxi driver can’t take the man. When he gets to the hospital, they will hold him responsible and make him pay if the man can’t.” Welcome to a world where individuals have the liberty not to have health coverage, and face the consequences for how they exercise that liberty. In Ghana, you don’t get treatment—sometimes even life-saving treatment—until you prove you can pay for it. Doctors will sit and watch you bleed while your friends and family cobble together money for payment, or rush to renew your health insurance policy. I once saw a four-year-old boy delivered to a rural health clinic after he ran onto the highway and was hit by a motorcycle. There was nothing the clinic could have done to save him. His mother spent his last moments not by his side, but running desperately through the village to get his insurance card. The issue of allowing indigent or liquidity-constrained individuals (those who could pay back their medical bills over time) to die aside, the serious economic issue here is that when the default assumption is that people cannot pay for health care, there are negative externalities that mean even those who can pay for care may not get it promptly, and as a result, may have worse outcomes. A man with thousands of cedis in his account should be able to get a taxi to the hospital; he should not be left on the road because the drivers fear he will be turned away on the hospital steps. A child with insurance should be treated promptly; he should not be left bleeding on a clinic table while his mother runs for proof of insurance. Those who support universal health care, or an insurance mandate, should not fail to recognize the costs, in terms of our government budget deficit, burden on the poor, and loss of economic freedom. However, those who are opposed to it should recognize the full costs of that liberty as well. I often fantasize about plots to confound muggers and highway robbers. (I know, this probably suggests I need to go on more dates.) One of my favorite—and less disturbing—plots involves buying a knock off designer purse, filling it with rocks, and prancing around with it at Gumani intersection after dark. I take particular pleasure in picturing how the inevitable purse snatcher will stagger under the bag’s surprising weight, and the look of dismay on his face when he opens his hard-won prize.

This paper by Cormac Hurley of Microsoft suggests this might not be such a bad idea. The paper models the economic decision made by an attacker, taking into account the cost of initiating an attack, the payout if successful, the total number of viable targets, and the density of viable targets among the general population. The model shows that to make attacks economical, ability to identify a subpopulation with a high density of viable targets is key. The paper’s findings have important implications for how we might approach crime reduction strategies in Tamale. Generally, one can try to deter crime by increasing the cost of engaging in it, or by reducing the benefits. Increasing cost: You can do this in a few ways. First, you can increase the penalty if the attacker is caught. You can also increase the likelihood that the attacker is caught. Either way, you increase the “expected”, or average, penalty for engaging in crime. (The rarity of catching criminals in Tamale is the main reason I am sympathetic the high penalties imposed in vigilante justice here.) You could also do this by increasing the cost of attempting an attack regardless of penalty, say by forcing attackers to sustain injury in order to get a payout. Reducing benefits: You can reduce the benefits of attacks by reducing the frequency with which criminals get a payout (reducing the number of viable victims), or by reducing the amount of the payout if the attack is successful. While this may all seem obvious, the Hurley paper’s model sheds some light on the efficiency of different approaches. The model suggests that reducing the frequency with which attackers get a payout can have a much larger effect than increasing the cost of crime or reducing the amount of the payout. For instance, in one example in the paper, if an attacker can successfully identify viable victims 99% of the time, and the ratio of the payout to cost is 100, the attacker will end up attacking 32% of viable victims. If you reduce the payout to cost ratio to 20 (you could do this by reducing the payout by 80% or by increasing costs by 400%), then the attacker will attack about 15% of viable victims. However, if you reduce the attacker’s ability to accurately identify victims from 99% to 95%, the attacker will only attack 4% of viable victims. The challenge with crime in Tamale is that the cost of committing it is pretty low, due to lackadaisical policing, and the ease with which attackers can identify viable victims: white people out late are almost always a viable target. Increasing police vigilance will be difficult to effect, especially without risk of repercussions such as curfews and travel warnings that might lead organizations to avoid Tamale. The good news is that a strategy we can more easily implement—decreasing the percent of Tamale expats who are out late and are actually viable victims—is likely to be a much for effective strategy anyway. So what can you do? Make sure you are not a viable victim. Don’t carry anything that could be a payout for an attacker. Don’t do things that make you an easy target, like get drunk or carry bags that are easy to take away. Travel in groups, and in areas where help will come quickly. You have probably realized that a corollary to this is that increasing the total number of people who are out late, and are not viable victims, could be a very effective strategy to deterring crime. However, in the case of Tamale muggings, being a non-viable victim still carries risks, and I am not advocating that anyone go out at night with the goal of being a “false positive” in an attempt to reduce general crime. But if you see me at Gumani junction with a fancy bag that looks awfully full, you’ll know what’s up. Why fix it when you can make money off it?

The traffic light at the main intersection in Tamale is currently broken, at least for some directions. The police were there yesterday. Rather than directing traffic, they were arresting and extorting money from motorists who entered the intersection at the wrong time. The broken light appears to be a boon to the police. My guess is it will be a while before it gets fixed. One day at the Tamale office meeting:

Boss: “Okay, so who wants to join the monkey feeding committee?” Abu, whispering to me and Salifu: “I want to join the hongin committee.” Me: “The what?” Salifu: “You know, hongin. Hongin out.” He writes: “hanging” Me: “Oh! Americans say hAAAAAAngeen.” Salifu and Abu vainly try to suppress their snickers, and the boss glares at us. Ghana’s official language is English, and most people here speak it well. As in other English-speaking countries, however, the English spoken in Ghana doesn’t sound the same as what you hear in America. Newly-arrived Americans often struggle to understand, and be understood by, Ghanaians. To aid understanding, ex-pats often adjust the way they speak, trying to adopt Ghanaian vocabulary and accent. Are ex-pat attempts to speak “Ghanaian English” offensive? It can be nearly impossible to get around without it. As one of my ex-pat friends said, “You do what you have to do to be understood.” On the other hand, trying to emulate another accent almost always has awkward results. I cringe at the thought of trying to copy a British, Australian, or Southern accent, and would be truly annoyed if someone insisted in speaking to me Sarah Palin-style. Trying to change your accent can imply that the person you are speaking to is not sophisticated enough to understand other English accents. Several of my friends have been criticized for using Ghanaian accents in the workplace, on the grounds that it is condescending. I’ve had experiences in both directions. I’ve discovered that I will never be able to access money unless I direct taxis to the “bonk”, rather than the “baaaank”. But I’ve also been mortified when making a call to a Ghanaian, introducing myself with a slight Ghanaian accent, only to have the person respond in perfect BBC British English. I conducted an informal survey of the Ghanaians I work with, to see what they thought about ex-pats adopting Ghanaian accents and words. Here’s a sample of the responses: “You should try to make your words more clear for us.“ “It’s exciting and not offensive.” “Sometimes, when you try to pronounce it like we do, it sounds mocking.” “People expect you to try to change your accent. It’s helpful. “ “For those who are well-educated, they may feel like you are talking down to them.” “When expats try to speak pidgin, it’s funny.” “You should start normal, then if they don’t understand, then you can say it with the accent.” “When you go out in the community, it marks you as someone who has been here a while.” “When she speaks [without the accent], the guy is always turning to me and asking, ‘what did she say?’” “You don’t use ‘aba!’ right.” The Ghanaians I spoke to, all in our Northern office, had a range of education levels and experience abroad. They generally agreed that it’s not offensive when ex-pats try to speak in a Ghanaian accent. However, a couple of them noted that when a person does it in a mocking way, or uses a very severe accent with a highly educated person, it can be offensive. All of them thought that it was fine for ex-pats to adopt Ghanaian vocabulary, such as “small small”, “somehow”, or “this thing”. In fact, most said they don’t notice it as being different from our normal vocabulary. Learning local languages or even pidgin was universally lauded, although I was advised not to use pidgin in partner meetings. My conclusion, based on these responses and my own experiences, is that the idea that trying to copy a Ghanaian accent is offensive is overblown, at least here in the North. An honest effort to adapt your speech to make yourself better understood is often helpful, and at worst, will make you sound a little strange. One caveat might be using a particularly dramatic accent in a work setting, as some may see the implication that they can’t understand an American accent as an implication that they are not educated. Some tips for Americans speaking to Ghanaians in work settings: 1. Start by telling the people you are talking to that they should let you know if you are speaking too quickly, or if there is anything they don’t understand. 2. Speak slowly. 3. Enunciate your words. 4. Don’t try to copy exactly how Ghanaians say every word, just those necessary in order for them to understand. For example, you don’t need to say “wah-tah” to ask for water. Go ahead and say “waa-terrr “, in all it's nasal glory. 5. Pay attention to how you talk to people. It’s easy to get in the habit of talking one way to taxi drivers, and carry that into other conversations, where it is less appropriate. Talking in a Ghanaian accent won’t actually help that Australian guy understand you any better. Just so you all know, we expats were being ironic about racism before “hipster racism” was even a thing. If you sit down for beers with a group of expats living in Ghana, race and culture will come up sooner or later. We ironically call ourselves Salimingas. We ironically call each other out for chewing our fufu. And we ironically sing and dance to the “African Man” song, professing our need for “ a strong, black man to handle my love…” Most white people in America have the luxury of not thinking about race if they don’t want to. And let’s be honest—most don’t want to. (If you are white, test yourself: when was the last time you thought of yourself as white? Do you feel uncomfortable calling yourself white?) White people in Ghana don’t have that luxury. The way people see you and treat you reminds you that you are the “other”. In Ghana, this isn’t at all subtle. I’m pretty comfortable saying I’m white in part because small children tell me I am every day. Race is a much more present topic for white Americans in Ghana not only because we suddenly find ourselves the minority, but also because skin color and race are often talked about in frank and open ways that would be startling in the states. The other day I was at the bank with a surveyor, and he told our place in the queue of Ghanaians was “just behind that colored guy.” My first impression was to think he meant the one guy wearing bright orange robes, but the ostentatiously dressed man was nowhere near where he pointed. My next thoughts were a) wow, “colored” is an antiquated term, and b) …um aren’t all those guys colored?, which I immediately felt racist for thinking. My surveyor clarified that, like the term “fair”, “colored” referred to people with slightly lighter skin. (Side note—as in the states, skin tone among Ghanaians is not completely neutral. Use of skin lightening crèmes is extremely widespread among Ghanaian women.) Being able to talk and joke about being white in Ghana is an important mechanism for coping with it. When small children climb out of the sewer and reach out and touch you, you can get annoyed that your skin color makes you a petting zoo object for kids that just climbed out of a sewer, or you can laugh and ask them if white skin feels any different than black skin. When people yell “white man” at you, you can quietly seethe, or yell “black man!” back. When a taxi driver quotes you a price three times the market rate, you can get angry, or you can pull out your most dramatic Dagbani accent and yell “oh, aba!!” (why, or wtf!?) When that driver later tells you he wants to marry “a white”, you can get annoyed or tell him your other husbands wouldn’t like you to marry again.

Is this bad? In the states, “hipster racism”—making stereotypical statements about race with the implication that it’s okay because you aren’t actually racist—has been roundly condemned in the blogosphere. The logical fallacy here is one that might be ascribed to hispterism in general: you may be drinking PBR ironically, but you are still drinking PBR. You may be saying racist things ironically, but you are still saying racist things. Either way, you are contributing to the proliferation of the object of your irony. PBR won’t go off the market just because you were being ironic when you drank it, and stereotypes won’t go away just because you are being ironic when you voice them. Hipster racism naively—and wrongly—assumes that racial stereotypes no longer have the power to harm. This doesn’t mean that all racially- or culturally-based humor need be taboo. Such humor can be effective at addressing problems that otherwise might be difficult to talk about. And let’s be honest—when the Ghanaian dancers at AllianceFrancais dress up in white face and chase women with comically inflated butts, it’s actually kind of funny. In determining what humor is harmful, here are some things I think should be considered: 1. Whether the humor perpetuates the stereotype or challenges it. Humor can be a powerful tool for bringing up stereotypes and revealing their absurdity. Teasing a child about touching you, or calling someone “black man”, can humanize you and make the person think about what he or she just said or did. 2. The connotations of the stereotype. Somehow I doubt white people in Ghana will suffer much if they have a reputation for chewing their fufu. Stereotypes about groups being lazy, or uneducated, or mean, etc., have a lot more potential to harm. 3. Whether the group targeted disadvantaged. The truth that a lot of white Americans may not realize, or may be uncomfortable with, is that power matters. Racial stereotypes have a lot more power to damage when they come from a privileged majority than an underprivileged minority. That is not to say that minorities get a free pass—I have been personally hurt by racism directed at me by members of a minority race in America—but the stereotypes held by these groups have never prevented me from getting a good education or good job, or having access to goods and services. The power of negative stereotypes rings hollow for groups that have the advantage of power and privilege. Members of privileged majorities have a greater responsibility not to be nonchalant about the impact of the stereotypes they throw around. 4. Whether the group targeted is you. Laughing at yourself is generally braver, more therapeutic, and less likely to cause harm than laughing at others. Targeting your own demographic isn’t a blanket pass, though. You should be aware that your comments reflect on others of your group. I was once horribly disgusted by some comments a black American made to me about his race. I later wish I had asked him if he would be comfortable with someone referring to his mother, or sister that way. That’s a good rule: if you wouldn’t find the joke harmless and funny if directed at someone you care about, it’s not funny if directed at yourself. Next, you should be aware of what a statement about your own group might imply about other groups. For example, if I say that if Americans who had to wait two hours in line at GCB would riot, I am also making a statement about Ghanaian’s willingness to do the same. In general, I think that race and racism should be talked about a lot more everywhere. But an important corollary is that when it comes to those issues, people need to listen and think a lot more too. I’ve heard Ghanaians insist with absolute certainty that white people aren’t charged higher prices in Ghana. Similarly, I bet there are a lot of people who aren’t aware of the extent to which racism affects minorities in America on a daily basis. For instance, there are still plenty of businesses where black patrons aren’t welcome. I once posited that it is harder to be black in America than white in Ghana. A friend of mine (also white) thought the opposite. The point is, racism is hard on everyone. Humor related to racism should be a tool to ease that burden, not increase it. Surveyors in our organization have coined the phrase "IPA reduction" to refer to the weight loss that commonly occurs among staff at all levels during and IPA survey.

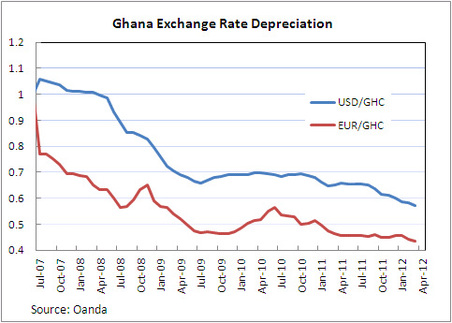

I recently received a spam comment on one of my old blog posts: "I want to reduce my fats and gain my physique back. so i like the tips you have shared here." The post was about how to survey people about their perceived risk of getting sick, but anyway.... In honor of all spammers who want to reduce their fats, here are the secrets of the IPA reduction: 1. Always be sure to be deep in the bush during lunch time, so you can't eat. 2. Stay in places where the only thing you can buy to eat after 7pm is plain rice. 3. When you get tired of plain rice and crave vitamins, eat nothing but a head of cauliflower or 5 carrots raw for dinner. 4. Get malaria, food poisoning, or a parasite. Failing to wash your cauliflower and carrots will be conducive to this. 5. Spend lots of time walking around villages and pushing your moto out of mud and sand. 6. Stress out constantly. Work long hours so that you are too tired to eat. So that's the secret to the IPA Reduction. Of course, if someone comments that you have "reduced" here in Ghana, it's usually not a complement, and tips above are not actually advisable. (Except #5. Pushing your moto out of the mud is always advisable.) The good news is, the IPA Reduction can be avoided by taking the time and effort to plan to have healthy and satisfying food around even when doing field work. The Ghana Cedi has depreciated noticeably in recent months. Similar depreciations were seen in 2000 and 2008, which, like 2012 were election years. (In 2004, also an election year, the cedi did not depreciate much.)  By the way, the actual currency code for the Ghana cedi is GHS. GHC refers to the old cedi. International finance nerds love currency codes. Does the Ghana cedi experience election year blues? If so, why? To address this question, I examine a few alternative explanations for the depreciation of the cedi: 1. The cedi depreciates in election years due to uncertainty about Ghana’s political and economic future. Uncertainty could result in cedi depreciation if it leads investors to pull their money out of Ghana, or to hesitate to invest in the first place. With the lead-up to the election looking more tumultuous than previous elections, and recent unrest in other West African countries, it would seem investors have reason to be cautious. It’s hard to find data to test this theory right now, as foreign investment data usually come at a lag. Foreign investment was strong in 2011 compared with 2010, but that says little about developments in the last half year or so. Uncertainty could also lead to depreciation if the cedi falls under speculative attack. The Bank of Ghana has attributed some of the depreciation to speculation that drives down the value of the cedi. (http://www.bog.gov.gh/privatecontent/MPC_Press_Releases/50th_MPC_Press_release-_Final_Copy.pdf) 2. The cedi depreciates in election years due to politically-motivated expansionary monetary policy by the Bank of Ghana. The incumbent party would benefit from a strong economy come election time. Short-term economic growth can be encouraged through expansionary monetary and fiscal policies. Increasing the money supply, however, eventually leads to inflation, which hinders the economy. The Bank of Ghana has actually raised policy interest rates in recent months, but you can’t necessarily look at policy interest rates alone to see if monetary policy is expansionary. Here’s why: the government of Ghana has been spending a lot of money (typical of an election year.) Normally, this would push up the government’s borrowing costs, and raise interest rates generally. However, if the central bank keeps rates constant rather than letting them rise, this has an expansionary effect. A better measure to look at is inflation. One-year inflation rates appear to be pretty steady, but these do not reflect very recent trends. The trouble with looking at monthly inflation is that prices in Ghana are highly seasonal, rising in the spring and then falling after harvest, and seasonally adjusted series are not released. Inflation in January and February was only somewhat higher than inflation in those same months over the last few years. While the key statistics that would be indicative of expansionary monetary policy are inconclusive at this point, the Bank of Ghana does acknowledge some other indicators of looseness. The Bank mentions that credit has eased, meaning money is easier to get, and that starting in 2011, there have been signs of liquidity overhang—meaning that banks have more cash than they want, causing interest rates to fall. The Bank mentions that these lower interest rates on cedi assets could be driving investments to other currencies with a higher rate of return. 3. The cedi depreciation is only coincidental to the election year, and is driven by other factors, including global economic conditions. There are some other factors that could be driving cedi depreciation. The first, mentioned by the Bank of Ghana, is that the depreciation is driven by demand for foreign currency to buy imports. Despite strong exports of oil, gold and cocoa, Ghana’s imports are growing faster than exports. A second possibility is that economic trouble in Europe is having a negative impact on the funds that are available to go to Ghana. This could account for a decline in investment in Ghana, if indeed such a decline is occurring. Remittances, however, appear to have remained robust, according to the Bank of Ghana. So what do I think? I think it is possible the election is having an effect, either on foreign investment, or on speculation in the currency market. I also think that the Bank of Ghana’s policies, politically motivated or otherwise, are responsible for it. While political turmoil is hard to address, a central bank can easily punish speculators and attract investors by raising interest rates. It appears that the Bank of Ghana is now taking steps to do just that, but earlier action might have nipped the depreciation and any speculation in the bud. My guess is that growing imports and a stagnant global economy may play roles, but not central ones. The West African CFA Franc, for example, has actually risen against the dollar since the beginning of the year. This suggests that at least some of the cedi’s downward trend is specific to Ghana’s. Luckily, that means that Ghana has the power to change it. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed