|

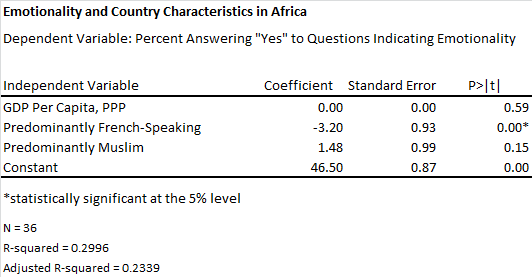

Gallup recently published results of a global poll on people's propensity to express or report feeling emotions. The Washington Post has a nice color-coded map of the results here. While some regions exhibit trends-- the Americas are bubbly with emotion, while the former Soviet Union is more somber-- Sub-Saharan Africa has a lot of variation. What country characteristics might be associated with increased emotional expression in Africa? I decided to test the relationship between emotionality and wealth as measured by PPP-adjusted GDP per capita, predominant language (a proxy for colonial influence by France or England), and whether at least half the population was Muslim. I used a linear OLS regression; results are below: There was no significant relationship between wealth and emotionality for the African countries. Countries with a Muslim population of at least 50 percent had a slightly higher average emotionality score, but the difference was not statistically significant.

People in Francophone Africa were, on average, 3 percentage points less likely to report expressing or feeling emotion, a result that was statistically significant. This may not sound like much, but it's a whole standard deviation below the mean emotionality score. (The model also explains more than a quarter of variation in African countries' emotionality scores!) So why are the Francophones less effusive? A couple hypotheses: 1. Maybe when translated into French, the survey was less likely to result in positive answers for some reason. 2. The Francophone variable might actually be capturing regional variation, such as lower emotionality in West Africa. 3. The French colonial cultural influence may have included elements of less emotional expression. The first issue is hard to address (language and cultural translation is always an issue when trying to compare social tendencies across cultures.) Putting in regional variables could address the second issue. Another interesting thing to look at would be the impact of political instability. My data, in .dta format for stata, are here: /uploads/1/7/1/1/1711915/africa_emotionality.dta

14 Comments

Surveyors in our organization have coined the phrase "IPA reduction" to refer to the weight loss that commonly occurs among staff at all levels during and IPA survey.

I recently received a spam comment on one of my old blog posts: "I want to reduce my fats and gain my physique back. so i like the tips you have shared here." The post was about how to survey people about their perceived risk of getting sick, but anyway.... In honor of all spammers who want to reduce their fats, here are the secrets of the IPA reduction: 1. Always be sure to be deep in the bush during lunch time, so you can't eat. 2. Stay in places where the only thing you can buy to eat after 7pm is plain rice. 3. When you get tired of plain rice and crave vitamins, eat nothing but a head of cauliflower or 5 carrots raw for dinner. 4. Get malaria, food poisoning, or a parasite. Failing to wash your cauliflower and carrots will be conducive to this. 5. Spend lots of time walking around villages and pushing your moto out of mud and sand. 6. Stress out constantly. Work long hours so that you are too tired to eat. So that's the secret to the IPA Reduction. Of course, if someone comments that you have "reduced" here in Ghana, it's usually not a complement, and tips above are not actually advisable. (Except #5. Pushing your moto out of the mud is always advisable.) The good news is, the IPA Reduction can be avoided by taking the time and effort to plan to have healthy and satisfying food around even when doing field work.  The heavily-fortified Ivory Coast border Some of my respondents are in Ivory Coast. They end up in our sample because they have visited health facilities in Ghana. Why do Ivoirians come to Ghana for health care? Ghana has a very affordable national health insurance program. It’s not easy in rural areas to verify who lives where, so Ivorians in border areas occasionally sign up for health insurance, reporting that they live in a village on the Ghanaian side. Sometime they even give a typically-Ghanaian name, in place of their French-ier real one. This is bad for Ghana’s government budget, but it’s bad for us too, because it means that we are trying to find respondents with fake names, and we don’t even know what village they come from. Our typical strategy is to go to the handful of villages near the border, ask for anyone who might have visited the Ghanaian health facility, and see if they are the person we are looking for. You can imagine, when we walk in and essentially ask “So anyone around here defrauding Ghana Health Services?”, how many people yell “Me, me!” Surprisingly, though, we actually find people. I spent one day serving as moto driver for one of my surveyors, Nana, in the border area. The road was rough—in many places impassable by car—and the surveyor had never been on a moto in his life. When we first arrived at the health facility, still in Ghana, I asked the surveyor how far it was to the border, expecting it to be maybe a mile or two. He pointed to a spot two meters to my left. We crossed into Ivory Coast about three times that day. Most of the borders weren’t even marked. There was one border crossing where a couple of Ivoirian border police were playing cards. They were happy to give us directions to the Ivorian village we wanted to visit. Once across the border, not much changed, except that people in rural villages spoke French the same way they speak English in Ghana—that is to say, not much. I was able to communicate more with my tiny bit of Twi than with my more extensive (if badly pronounced) French vocabulary. Nana, fluent in Twi, was fine. The day ended with several unfruitful hours looking for “Sabrina”. I felt pretty good though. On the drive home, I smugly told Nana that there were not too many PAs in IPA who would have driven these roads and asked for directions in French and Twi. He winced and rubbed his seat as we hit a bump, and I am pretty sure he wished he had been with one of those other PAs. Chris Blattman recently blogged about the moral absurdity of running regressions where the dependent variable is “war deaths”. While looking at death, illness, hunger, and poverty through the lens of statistics may seem rather reptilian, I think many researchers have emotional reactions to the data they work with. For me, these connections hit hard and unexpectedly, often when I am tired and working late, and they come despite efforts to be dispassionate about the data I am looking at.

Survey editing is prime territory for emotional connections to data. When editing surveys, you see the story of an individual respondent in a way that you don’t when you are looking at columns of aggregated data . Once, I was reading a survey where a respondent reported that a household member had experienced a headache. I turned the page to the question on outcomes of health events. The headache had resulted in death for that household member—despite the family spending an amount equal to roughly one-fourth of Ghana’s annual GDP per capita on health care for that individual. The shock of the outcome hit me almost physically. Another respondent reported testing positive for HIV. Sitting alone in the Tamale office at night, I struggled to pull myself together, shoo the bugs out of my computer keyboard, and make my way home. The “death” outcome became a dependent variable in regressions I later ran looking at determinants of health outcomes. Luckily, there were very few events of death in my sample. We also looked at a number of food insecurity events: individuals going to bed hungry, or not eating for an entire day, for example. These were, unfortunately, common among our respondents. I don’t deal well with feeling hungry myself, and for me, food insecurity statistics evoke desperately sad, human images: a man’s disappointment at foregoing his favorite fish; a young student trying to sleep before an exam while feeling the distracting ache of hunger; an elderly woman going without food for a day so her grandchildren can eat; a mother having to tell her thin children there is no food today. These emotional connections often seem like a distraction, something that prevents us from approaching our analysis logically and dispassionately. In all honesty, part of my attraction to quantitative research tools might be to protect myself from these types of emotional connections to problems. But it our ability to have these connections, even through layers of statistics, is tied to a very deep belief in the importance of what we are doing, and that counts for something. Hey, at least I’m not working in finance. A major study was recently found to contain an error that led the study to overestimate the cost-effectiveness of deworming by a factor of 100. (Note that this was NOT the IPA RCT study of deworming in Kenya, which found deworming to be highly cost-effective in part due to large positive spillover effects.)

This is the type of thing that keeps project associates up at night-- when we aren't staying up trying to track the surveys that came in that day, writing .do files to analyze our data, or drafting reports containing our results. The fact that we work long hours, on tight schedules, sometimes while delirious with malaria doesn't help. My most recent report was 120 pages long, and based on what must be tens of thousands of lines of stata code. It's hard to believe there are zero errors in that code. So how I am going to sleep tonight? I know two sets of eyes have looked over the code used in the analysis. I've looked critically at the findings to see if they make sense, and if they are consistent with the rest of the data. We might not be able to catch everything (were there some observations I should have recoded for that question?) But hopefully we can catch the "factor of 100" errors. Also, I am really tired. Ramadan is coming up, and in Northern Ghana, that means a large portion of staff, partners, and survey respondents will be going without food and water during daylight hours. If you aren’t Muslim, sometimes you forget that other people are fasting, or to be unaware of how this may affect their work and schedules. Some rookie mistakes I have seen:

· One of our interns wanted to do something nice for the office, so he brought in donuts at 2pm- prime hunger time for many fasters. · A friend of mine was working with a Ghanaian staffer, and noticed she wasn’t eating anything. Feeling bad, she proceeded to offer the Ghanaian shares of everything she ate that day. It wasn’t until later that she realized the Ghanaian must have been fasting. · A staff member scheduled a lunch meeting with partners. The partners came without complaint, and the staff member was chagrinned when none of them ate anything and she remembered it was Ramadan. To avoid being a jerk to hungry people during Ramadan: 1. Find out when Ramadan is. In many cases, the beginning and end of Ramadan are set locally, based on sighting the moon in that location. 2. Set schedules that allow people to break fast in their accustomed manner. This usually means being at home for sundown. 3. Don’t push food on people. It’s fine to offer, but if someone declines, try to remember that they may be fasting, so don’t keep offering all day. 4. Be aware of the effect that fasting may have on energy levels and mood. Most fasters will do the work they need to without complaint, but think twice about asking people to work late. 5. Remember the people who aren’t fasting. Don’t assume people can skip lunch breaks. 6. Don’t pity the fasters. Ramadan is a month for celebration, and most people fast gladly. They won’t mind you eating in front of them, especially if you aren’t wafting the fumes from your super-smelly food at them. 7. Consider trying to fast, if only for a day. It will show solidarity and make you more sensitive to those who are fasting. I fasted during Ramadan in Tamale last year. This year, I will be fasting in Accra for as long as my Tamale team is in the field. If you decide to try fasting, here are some tips: · Don’t give up early. The first three days are the most difficult. Get through those, and it gets easier. · Eat before sunrise. Even if you aren’t hungry, make yourself do it. It will help you get through the day. · Don’t fight the hunger. The more you try to ignore it, the more you will focus on it. Accept that it is there, and learn to function with it. · Recognize your moods. Be aware of how fasting is affecting your mood. Work on changing your reaction to hunger, or be on guard against letting the mood affect your behavior towards others. · Be aware of your health. Consider whether you want to include water in your fast, especially if you work in hot environments or exercise during the day. Muslims fast if they can; young children, pregnant women, and others for whom fasting could pose a health risk are not expected to fast. · Don’t stay up drinking all night. A hangover is no fun when you can’t have pizza. This is especially important if you aren’t drinking water, as you can easily get dehydrated. · …Unless you also stay up eating all night. I spent one night last Ramadan at a friend’s house mixing drinks and cooking a new meal every few hours, till the sun came up. The next day was the easiest day of Ramadan. Most surveys have a field at the end for comments where surveyors can record anything important about the survey not addressed elsewhere. My survey did—and I found that most of the time, surveyors record nothing important in the comments field. Typical entries include:

1. The obvious: “The survey was completed successfully” 2. The nice but not particularly important: “Respondent was very friendly” 3. Somewhat useful information about attitudes toward your survey: “The respondent complained it was too long” “The respondent hated the food security section” 4. The confusing: “No” 5. The amusingly mis-written: “Good Intercourse” (An actual comment from one of my friend Linda’s surveys) Occasionally, a surveyor will use the comments section to record very important information about seemingly contradictory information in the survey. For example, if no household head is recorded, the surveyor might note that the household head is working in another region and thus didn’t meet the residence requirement to be recorded as part of the household, even though that person has decision-making power for the household. Another example: if a respondent opts out of a question or section, this can be recorded so that the information is not thought missing. This is how the comments section should be used. Reducing comments to only include important information has the benefit of reducing time-consuming string field data entry, and reducing the number of comments that must be sorted through during analysis. How do you improve use of the comments section? Next time I do a training, I will include a section on using the comments field—giving examples of useful comments and unnecessary comments, and emphasizing that it’s okay to leave the section blank if there is no important information to record. This is also an area where electronic surveying has an advantage. Many electronic survey platforms allow surveyors to add comments on each question. This focuses the surveyor on recording information that is relevant to understanding survey responses. It also allows the surveyor to address an inconsistency as soon as it comes up, rather than waiting till the end of the survey, when the surveyor may have forgotten about the issue. In Ghana, large plastic bags, printed with plaid or otherdesigns, are prolific. The bags arecalled “Ghana Must Go” bags. I haveasked numerous Ghanaians why they are called this. They reply that Nigerians call them that, forunknown reasons. I finally learned thatthe name originates from Nigeria’s political turmoil in 1983, when manyGhanaians fled Nigeria. They hastilypacked their things in these bags.

Upon discovering these bags, I decided that they would be agood inexpensive option to carry our surveys, and dispatched the field managersto buy a couple for each of their offices. The tough field managers, who are a sophisticated combination of book-smartand street-smart, came back with bags printed with cartoon bears and cartoonpigs. Secretly amused, I asked themwhether they thought the print on the bags reflected the seriousness and professionalismof IPA. The next day a third bagappeared bearing cartoon Mickey Mouse. The bags held up during the course of the surveying,ferrying blank surveys to the field and completed surveys back to Tamale. StuffNigerianPeopleLike.com claims a GhanaMust Go can carry a child and his dog for miles. When I took our complete batch of surveys toAccra, the bags weighed in at 35 kilo per bag, which unfortunately, seems to bemore than a child-dog combo. My bags weredestroyed in one bus trip to Accra. To add injury to insult, plastic handles onthe bags chafed my palms, which have been peeling unattractively for weeksdespite copious amounts of shea butter. The surveys ultimately made it to the data team, whopolitely did not comment on the layers of dust the surveys had acquired duringtheir sojourn through the Northern Region. The lesson is that while I highly recommendGhana Must Gos for children, dogs, and objects with high volume-to-mass ratios,I do not recommend them for objects with density greater than or equal to adusty IPA survey. I'm starting to get data-- even if it's from training and not real-- which is exciting and daunting at the same time.

I haven't had time to do much with the numbers yet, but every survey has a place for the surveyor to write in comments about how the survey went, and I scanned through some of those. My favorite comment so far? "NO." Can't wait to look that one up! |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed