|

I recently visited Monrovia, which in the words of P-Square, chopped my money. Food, accommodation, and transportation are much more expensive in Liberia than in any other West African country I have visited. It’s true that Liberia is a post-conflict country full of UN staff, who, when not struggling to help Liberia maintain its stability and get on its feet, are probably struggling to find enough things in Liberia to spend their money on. But Liberia also differs from other countries in West Africa in that the U.S. dollar is used in parallel to the Liberian dollar. Is it possible that dollarization could also contribute to higher prices? First, a couple of observations about money and prices in Liberia. The U.S. dollar and Liberian dollar are used interchangeably. There is no place that accepts only one. Generally, the U.S. dollars are used as large denomination bills, and the Liberian dollars are used in place of U.S. coins. (I didn’t see a single coin in Liberia.) Prices of imported goods in Liberian supermarkets are roughly the same as the dollar equivalent of prices of imported goods in Ghanaian supermarkets. Gas prices also seem to be similar, though a bit more expensive. It seems that the main difference in prices stems from differences in prices of services.

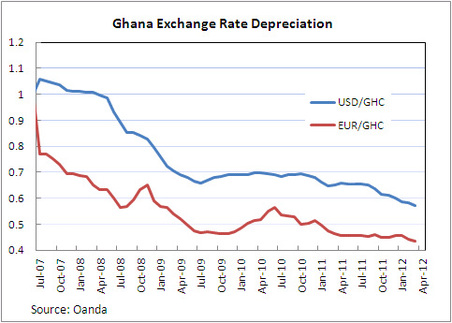

The fact that price differences are concentrated in services, or non-tradeables, makes me suspect that the high prices are in part due to dollarization, and here is why: in a non-dollarized economy, like Ghana, which uses the cedi, if the Ghanaian government pursues a loose monetary policy, the currency will depreciate relative to the U.S. dollar. This doesn’t affect the dollar price of imported goods—these are bought in dollars, so their price in Ghana cedis will just be inflated so that the equivalent price in dollars is unchanged. Other prices in the economy, however, are sticky. Employees have contracts with set wages, and people are used to paying a given price for hiring someone to sew a dress. As a result, the price of these non-tradeables stays constant in cedis, but becomes cheaper in dollar terms. (Note about monetary policy transmission in West Africa: In West Africa, business and consumer loans are much scarcer. So loosening monetary policy doesn’t lead to cheaper credit very quickly. It does, however, mean that cedi funds are more readily available to banks than U.S. dollar funds, which puts pressure on the exchange rate. So monetary policy transmission through exchange rates is more important in countries like Ghana, and happens more quickly, relative to transmission through interest rate mechanisms, compared to countries where large portions of the population have access to credit.) What this means is that Ghana, if has a trend of depreciating currency, can have low overall prices in dollar terms because, in dollar terms, prices for non-tradeables have fallen. Liberia, since it is dollarized, won’t see this effect. If Liberia prints more Liberian dollars, the exchange rate may change, with the value of the Liberian dollar declining, but prices in dollars will stay the same. This does, of course, attribute a level difference to an effect that applies to differences in rates of change, and my observations regarding prices of goods and services are anecdotal (Liberia doesn’t have good CPI data.) If you have comments on the plausibility of the theory, please comment!

5 Comments

The Ghana Cedi has depreciated noticeably in recent months. Similar depreciations were seen in 2000 and 2008, which, like 2012 were election years. (In 2004, also an election year, the cedi did not depreciate much.)  By the way, the actual currency code for the Ghana cedi is GHS. GHC refers to the old cedi. International finance nerds love currency codes. Does the Ghana cedi experience election year blues? If so, why? To address this question, I examine a few alternative explanations for the depreciation of the cedi: 1. The cedi depreciates in election years due to uncertainty about Ghana’s political and economic future. Uncertainty could result in cedi depreciation if it leads investors to pull their money out of Ghana, or to hesitate to invest in the first place. With the lead-up to the election looking more tumultuous than previous elections, and recent unrest in other West African countries, it would seem investors have reason to be cautious. It’s hard to find data to test this theory right now, as foreign investment data usually come at a lag. Foreign investment was strong in 2011 compared with 2010, but that says little about developments in the last half year or so. Uncertainty could also lead to depreciation if the cedi falls under speculative attack. The Bank of Ghana has attributed some of the depreciation to speculation that drives down the value of the cedi. (http://www.bog.gov.gh/privatecontent/MPC_Press_Releases/50th_MPC_Press_release-_Final_Copy.pdf) 2. The cedi depreciates in election years due to politically-motivated expansionary monetary policy by the Bank of Ghana. The incumbent party would benefit from a strong economy come election time. Short-term economic growth can be encouraged through expansionary monetary and fiscal policies. Increasing the money supply, however, eventually leads to inflation, which hinders the economy. The Bank of Ghana has actually raised policy interest rates in recent months, but you can’t necessarily look at policy interest rates alone to see if monetary policy is expansionary. Here’s why: the government of Ghana has been spending a lot of money (typical of an election year.) Normally, this would push up the government’s borrowing costs, and raise interest rates generally. However, if the central bank keeps rates constant rather than letting them rise, this has an expansionary effect. A better measure to look at is inflation. One-year inflation rates appear to be pretty steady, but these do not reflect very recent trends. The trouble with looking at monthly inflation is that prices in Ghana are highly seasonal, rising in the spring and then falling after harvest, and seasonally adjusted series are not released. Inflation in January and February was only somewhat higher than inflation in those same months over the last few years. While the key statistics that would be indicative of expansionary monetary policy are inconclusive at this point, the Bank of Ghana does acknowledge some other indicators of looseness. The Bank mentions that credit has eased, meaning money is easier to get, and that starting in 2011, there have been signs of liquidity overhang—meaning that banks have more cash than they want, causing interest rates to fall. The Bank mentions that these lower interest rates on cedi assets could be driving investments to other currencies with a higher rate of return. 3. The cedi depreciation is only coincidental to the election year, and is driven by other factors, including global economic conditions. There are some other factors that could be driving cedi depreciation. The first, mentioned by the Bank of Ghana, is that the depreciation is driven by demand for foreign currency to buy imports. Despite strong exports of oil, gold and cocoa, Ghana’s imports are growing faster than exports. A second possibility is that economic trouble in Europe is having a negative impact on the funds that are available to go to Ghana. This could account for a decline in investment in Ghana, if indeed such a decline is occurring. Remittances, however, appear to have remained robust, according to the Bank of Ghana. So what do I think? I think it is possible the election is having an effect, either on foreign investment, or on speculation in the currency market. I also think that the Bank of Ghana’s policies, politically motivated or otherwise, are responsible for it. While political turmoil is hard to address, a central bank can easily punish speculators and attract investors by raising interest rates. It appears that the Bank of Ghana is now taking steps to do just that, but earlier action might have nipped the depreciation and any speculation in the bud. My guess is that growing imports and a stagnant global economy may play roles, but not central ones. The West African CFA Franc, for example, has actually risen against the dollar since the beginning of the year. This suggests that at least some of the cedi’s downward trend is specific to Ghana’s. Luckily, that means that Ghana has the power to change it. After years of remaining a theoretical plaything for money nerds like me, nominal GDP targeting has suddenly become a thing. NGDP targeting has been getting love from economists across the political spectrum, which naturally means laypeople across the spectrum are responding with skepticism. Drudged up from what I remember from Prof. Burdekin's Money and Banking, I present the basics of NGDP targeting:

What is NGDP targeting? NGDP targeting means that the central bank sets monetary policy to target nominal gross domestic product, that is, GDP that is not adjusted for price level. The beauty of NGDP targeting is that since both prices and output are part of NGDP, both of these things influence monetary policy even though only one metric is considered. Either NGDP level, or growth, can be targeted. Why liberal economists like it: liberal economists tend to be more supportive of considering economic growth, not just inflation, when setting monetary policy. NGDP targeting naturally includes growth as an input. Why conservative economists like it: conservative economists tend to prefer simple, transparent rules for monetary policy, as opposed to opaque systems that give broad discretion to policy makers. NGDP targeting is easy to understand and easy to see if policy makers have met their goal. So how is it different? The Federal Reserve has what’s called a dual mandate—they are charged with considering both prices and economic output when setting policy. (Some central banks, like the European Central Bank, are charged with only considering prices.) The Federal Reserve does not commit to following any particular formula for setting monetary policy, but it is largely believed to behave as if it follows the Taylor Rule, meaning it considers deviations from target inflation rates and target employment rates. Targeting NGDP would provide the Federal Reserve with a mandate to specifically target deviations from output targets. There are other things a central bank can consider besides prices, employment, and output when setting policy, such as money growth and asset prices. A central bank with broad discretion can consider all of these things, but this comes at the cost of making monetary policy decisions less transparent. But what about QE2?? So where do things like quantitative easing fit into all this? It is important to distinguish between the tools used to set monetary policy and the tools used to implement monetary policy. Tools used to set monetary policy, such as Taylor Rules, money growth target, or NGDP targeting, tell the central bank whether they need to tighten or loosen policy. The tools used to implement monetary policy generally remain the same regardless of what policy prescription tool you use. If interest rates are at zero, and inflation is low and unemployment high, you need quantitative easing to get to your targets. If interest rates are at zero and NGDP is below target—guess what, you still need quantitative easing to get to your target. Targeting Growth vs. Level If you are going to target NGDP, you have to decide whether to target NGDP growth rate or NGDP level. Most of the cool kids in economics prefer level targeting. Level targeting has the benefit of allowing for catch up periods: after the economy has had a downturn, it natural that it have a period of both higher growth and inflation to catch up to where it would have been pre-downturn. So let’s do it? To me, whether NGDP targeting should be implemented actually involves three different questions: 1. Should GDP be considered when setting monetary policy? The downside to considering GDP or other factors is that the central bank places less weight on price stability, which is bad if you are an inflation hawk. The benefit is that drops in GDP often lead drops in inflation or unemployment, so considering GDP can help the central bank adjust to new economic trends more quickly. 2. Should the central bank target levels rather than growth rates? When it comes to prices, levels are arbitrary—it’s change in prices that matter. That’s the primary logic behind targeting inflation rather than price level. However, as discussed above, it is natural for an economy that has been sluggish for a while to have a period of higher growth and higher inflation to “catch up” after a downturn, so monetary policy that accommodates this can make sense. This accommodation can actually help end a downturn more quickly—if during a downturn, people know they can expect extra high inflation in the future, they have an incentive to spend more now, stimulating the economy. The flip side to all this, which I haven’t seen discussed much, is that monetary policy lags the trends a bit. This sounds great when you are coming out of a recession, but what about when you are coming out of an expansion? Would the people keen to see accommodating monetary policy continue as growth picks up be equally keen to see tight monetary policy stay in place when growth comes to an end? 3. Should the central bank have a clearly defined rule? The benefit of a rule is that it provides transparency and sets expectations, and expectations are essential for effective monetary policy. The downside of a rule is less flexibility, and loss of credibility if the central bank fails to meet its targets. If you answered yes to all of the above, then NGDP level targeting is for you. Personally, I agree that a central bank with a dual mandate should consider GDP. However, I think that the central bank should have some flexibility in targeting levels versus growth, and that growth is sometimes the more appropriate metric. Moreover, I think that a central bank like the Federal Reserve, that has a high level of trust and credibility, has more to lose from committing to a rule like NGDP level targeting than it has to gain, since failure to achieve the target would hurt its credibility. As it is, the Federal Reserve can consider the policy prescriptions of an NGDP target, while also considering Taylor Rules, asset prices, and other economic data when setting monetary policy. NPR recently featured a segment on tipping, positing that while many people believe they tip to reward good service, they actually tip out of guilt for being served by another. The segment points out that people tend to tip at fairly constant rates, regardless of how good the service is, and more interestingly, the services that conventionally require tips in the United States are those where the person receiving the service is having a lot more fun than the server. People at restaurants and hotels tip; people at the dentist do not.

Guilt seems to make up a large share of my (admittedly under-average) emotional spectrum, so I find this very compelling. The segment points out a downside to this: tipping out of guilt may not be efficient. Tippers may give an amount larger than the value of the service to them, and tips that don’t vary with service quality don’t provide incentives for better service. Tipping norms in Ghana are quite different from those in the United States: tips are not necessarily expected for restaurant service, but for help with directions, with making a large purchase, or with loading bags onto a bus, a tip, or “dash” is expected. (“Dash” functions as both a noun and a verb.) Often, the services you are expected to dash for are services you don’t even want, and the tipper may even give money just to get someone to go away. The role of guilt in tipping is compounded in these situations by the uncertainty foreigners may have regarding tipping norms and by the income disparity between the average foreigner and the people who do these types of jobs in Ghana. The trouble with this is that the efficiency of the tip is further diminished. While guilt may make me a generally good tipper, as an economist, I also feel guilty when I tip for poor service or services I don’t want, thus providing poor incentives. Here is my advice on tipping in Ghana to maximize good incentives: Restaurants: Tipping is not mandatory for food service, though it becomes more expected the more upscale the venue. I highly recommend giving small tips/dashes that are very sensitive to the quality of service. At a local eating spot, 1 GHS is a good tip for basic service, and will likely get you a little extra attention next time you visit. At a nice restaurant in Accra, a 10% tip for good service seems to be well-received. The rarity of tipping in Ghanaian restaurants presents an opportunity to tie tipping to good service, so I would urge varying tips accordingly, giving nothing for poor service, and large tips for good service. Bags: If someone helps you carry your bag, it is very much expected you will give a dash. If you don’t want to, then be firm about carrying your own bags. Bus baggage: Small dashes are often expected for loading your bags under a bus. It is hard to avoid using this service. This is the context where I have found demands for dashes to be most outrageous. A dash should not be mandatory for this—I have seen supervisors yell at men who demanded a dash before loading bags. I would recommend resisting anyone who demands one before helping you. The dash should also not be large. I once encountered a man who refused my 1 GHS dash and demanded 2 GHS. I gave him nothing. I would not give more than 1 GHS unless your bags are many, or you receive some special assistance with them. Note that a dash for loading should not be confused with an actual fee for baggage. Directions: You should not have to pay a dash for directions. If someone walks a long way with you to show you where something is, a dash may or may not be demanded. If you don’t want to give one, don’t accept the escort. Assistance with purchases: If someone helps you locate, select, bargain for, and complete a substantial purchase, a dash may be in order. Things to consider: how much help you received, how much time and money you saved as a result of the help, and whether the person got any financial gain from your purchase. Generally, anyone who approaches YOU about buying something doesn’t need a dash. Household errands: If you have a guard or groundskeeper, the person will often run errands for you. You should dash to compensate for their travel costs and efforts. Professional services: Professional services outside a person’s normal job may require a dash, depending on the job and the organization a person works with. As an example, I had a document notarized by a judge in Tamale, and I paid a 5 GHS dash for his time and trouble. Stealth window washing: One of the strangest things about Accra are stealth window washers, who swoop in on a car waiting at an intersection, squeegee the front windshield despite the driver’s protests, and then demand a dash after. No matter how guilty you feel, please, please do not dash for this or other unwanted services that are forced on you; you will only encourage the practice. Further advice on tipping in Ghana (or anywhere else)? Please contribute in the comments! Chris Blattman’s blog recently critiqued an article by Dan Pallotta arguing that earmarking funds for programs with proven impact is actually less impactful than using the money for further fund-raising efforts. Pallotta makes an argument that spending on fund-raising allows you to, in essence, leverage your funds and get a much higher return on investment than you would if you’d spent that money directly on programs.

Blattman makes two counter points: 1. The effectiveness of the programs you are funding feeds back into your ability to use your money to raise more funds. 2. It’s not clear that lack of funds is the binding constraint in aid. I’m a bit skeptical of Blattman’s second point—I thought I was out here getting malaria to make sure that scarce development resources were spent on programs with the highest impact. I think it is more correct to think of funds and good practice as being similar to labor and capital—in most circumstances you can add more of one or the other and improve outcomes, but are most effective when increased together. I think Blattman’s first point is completely correct. Pallotta is right that fund-raising can increase impact, but program impact is fundamental to fund-raising effectiveness and meaning. Donors should be attracted by good programs. In a rational world with perfect information, donors would know exactly how much money they wanted to spend, and they would choose the program with the highest impact-per-dollar. This is how these institutional funders Pallotta is complaining about behave. However, in the real world, human behavior is less rational and more suggestible. If fund-raising can actually increase the number of dollars out there to be used on development, it can indeed be highly impactful. Note that fund-raising that just diverts funding from one project to another from a fixed pool of resources doesn’t get to claim this—unless the program it diverts money to is more impactful that the program it diverts money from. Which brings us to the next point-- if your programs don’t have impact, it doesn’t matter how much you leverage your dollars- you are just using more money badly. Palotta’s proposal to use seed money to fundraise is similar to the concept of hedge funds. Hedge funds can’t make huge returns without leveraging their initial funds with loans, but if they don’t put the leveraged funds in investments with good returns, they are just wasting everyone’s money. Palotta also argues that you often can’t know what is going to be impactful ex ante. That may be true, but that doesn’t mean you should throw in the towel and give up on trying to target impactful programs. Market investors often can’t know which stocks will take off, but no investor would throw money at one without trying to make an educated assessment of its future value. If funding truly is a scarce resource, you have to have some standard for choosing which programs to fund and which not to. Polatta may be right to encourage donors to allow their funds to be used for further fundraising, but this only makes sense in concert with an emphasis on evaluation. After all, what is the point of all that fundraising if you aren’t going to do anything good with it? And for fundraising to matter, Blattman must be wrong about money not being a binding constraint. If money is a binding constraint, then you can’t fund everything, and it becomes all the more crucial to have some way of assessing the best programs. I've spent 36 hours on Ghanaian bus trips in the past month, much of it watching Nigerian ("Nollywood") movies. The Cinderella story is a common theme in many of these movies: a poor village girl, or sweet middle-class modern city girl, meets a young African prince, who buys her lots of stuff, defends her from his disapproving parents, and takes her away to live in a palace.

I had an interesting conversation about women, love and money with several male Ghanaian colleagues the other day. All three of them agreed that women, in general, loved men for their money. One of them said that he was glad he married his wife My male American colleague gallantly came to the defense of my gender, and contended that while this might be true for some, it was untrue for most, and it was impossible to "love" anyone for their money anyway. One coworker suggested that American women were less likely to love a man for his money than Ghanaian women. With Nigerian Cinderella fresh in my mind, wasn't so quick to dismiss the attraction of money, but instead asked what was wrong with that? What we find attractive is influenced by our needs, and what society admires. Marriage has long been an economic union, and ability to provide economically has been necessary to that union, and socially admirable. And it is no more shallow than many of our other criteria for love-- which is a more accurate reflection of character, the looks a person was born with, or the money they earned? (We will put aside the money a person was born with for the moment.) The major difference between West African women and American women is that for West African women, economic survival is much less assured-- and hence a greater need. If the Cinderella fantasy still limps through American culture, it should be unsurprising to find it prevalent in West Africa, where many women do not have the luxury of discounting their mate's ability to provide economically. If men want women to marry them for attributes other than money, they should do all they can to empower women to provide for themselves, so they will have that freedom. Also, they should consider their decisions to have multiple wives and mistresses. When being able to provide for multiple women becomes a mark of status, it only reinforces the link between money and relationships. Treat women like people, not objects, and they will treat you as people, not meal tickets.  India has a new, attractively-designed symbol for the rupee. It’s a combination of the Latin letter “R” and the Devanagari “ra”. (It looks like this: र) I’m not sure yet what strokes I would use to write it: R-bar-bar, or bar-R-bar, but I approve. Now I think either China or Japan should come up with an alternative to ¥… For those interested, Slate’s The Explainer has a quick article about the origin of common currency symbols here. The Ghana cedi is noted with the symbol GH¢, or the ISO code GHS. (The ISO code for the rupee is INR; the U.S. dollar is USD, etc.) The name “cedi” comes from a word for cowry shell, which were once used in Ghana as currency. I am currently obsessed with change. Going to the market is an exercise in retaining as much small change as possible.

I was warned to jealously guard my one cedi notes and coins, but I did not realize how important this would be until I was trying to buy lunch the other day. I walked up and down the street, but no one could sell me fried cheese or avocados and give me change for my ten cedis. I was starved by the time I decided to go to the canteen and buy a full plate of jollof rice. Although my problem with small change is likely exacerbated by the disparity in income between me and most of the people living in Tamale (I take 100 cedis (about $70) out of the ATM at a time, where many people may earn only a few cedis a day), I believe the lack of small change is a problem for everyone. Many things are sold for less than 1 cedi, yet 10 cedi notes are prolific and coins are rare. I have heard there are businesses that will trade you 9 one cedi notes for your 10 cedi note. This problem may also be related to the recent re-denomination of the cedi; several years ago they chopped four zeros off the currency; what sold for 10000 cedis is now 1 cedi. The New York Times reports that playing sports as a child has a positive impact on women's income when they are adults. More boys than girls play sports in high school; about one in three high school girls plays sports compared with half of high school boys. In an era when the majority of the population is overweight, this is one more reason why both girls and boys should be given opportunities and encouraged to participate in sports.

According to NPR, this is the brainchild of Spike TV producer John Papola and libertarian economist Russel Roberts, together with rap duo Billy and Adam.

|

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed