|

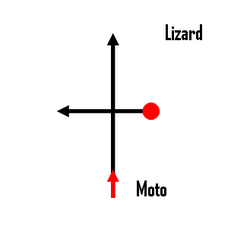

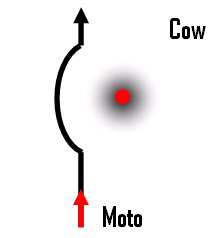

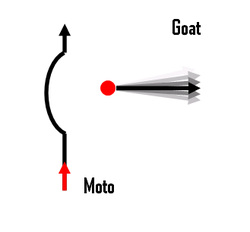

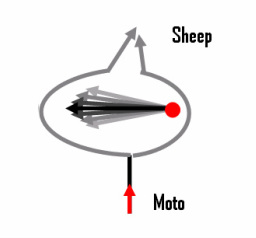

One of the most common hazards for moto drivers in Tamale, Ghana, is animals on the road. Learning how different animals will behave when a vehicle approaches is one of the key ways to keep safe driving moto in Northern Region. Here is what you can expect: In the diagrams below, the red represents the location and velocity of objects on the road at time 0. (Yes I know these can't technically be simultaneously measured but give me a break I am a social scientist.) Red points indicate zero velocity. The black represents the probable location of these objects during the time it takes the moto to move through that space on the road, with darker lines represent higher probability of the object being in that space.  Lizards are all over the place in Northern Ghana. Mostly they sit around and do push-ups or clamor over your walls making a racket. Occasionally they decide to cross the road. Their quick, flick-y movements may make you jump, but don't worry-- they will go straight across, and they are quick enough that the probability of lizard guts on your tires is low.  Even the white Toyota Landcruisers favored by overly-pampered, well-funded development workers won't go up against a cow in the road, and the cows know it. They won't move except under duress of a slipper wielded by a small boy. You will have to go around them. If they are many, be prepared to honk your horn in vain while they decide which side of the road they really want to be on.  Goats are the ideal animal to encounter on the road in Northern Ghana. Street smart and properly aware of their place in the road hierarchy, they will run away and off the road at the approach of a vehicle. The exception: goats often like to sleep on highways at night. Beware of groggy goats when driving early in the morning.  While goats are the ideal animal to encounter on the road, sheep are bane of Ghanaian drivers. Dismally stupid, they will invariably run directly into traffic. An experienced motorist will, counter-intuitively, plot a trajectory behind the sheep. The difference in behavior between sheep and goats makes distinguishing the two a key survival skill in Tamale. Remember: tail up, goat; tail down, sheep.  After a chicken perceives an oncoming vehicle while crossing the road, its velocity can be modeled with a random walk, plus a constant increase in speed of averaging 1 ft/second. Use this formula to calculate the most probable route of the chicken, and avoid it. Alternatively, just keep going. A chicken ain't no cow. In all seriousness, take care to watch for animals when driving in Ghana. If an animal is on the road, your first priority should be the safety of you and the people around you-- don't try to stop for a chicken or lizard if it would endanger you or others. If you hit and kill an animal of economic value (goat, sheep or chicken), and the owner is around, you may have to compensate the owner. Typical prices for strong, adult animals are 5 GHC for a chicken, 35 GHC for a goat and 50 GHC for a sheep (another reason sheep are the bane of drivers.) However, a sincere apology may be suffice. I heard about a man who hit and killed a goat, and after arguing with the entire village for an hour, was allowed to go on his way-- after he promised he would never ever hit another goat.

75 Comments

NPR recently featured a segment on tipping, positing that while many people believe they tip to reward good service, they actually tip out of guilt for being served by another. The segment points out that people tend to tip at fairly constant rates, regardless of how good the service is, and more interestingly, the services that conventionally require tips in the United States are those where the person receiving the service is having a lot more fun than the server. People at restaurants and hotels tip; people at the dentist do not.

Guilt seems to make up a large share of my (admittedly under-average) emotional spectrum, so I find this very compelling. The segment points out a downside to this: tipping out of guilt may not be efficient. Tippers may give an amount larger than the value of the service to them, and tips that don’t vary with service quality don’t provide incentives for better service. Tipping norms in Ghana are quite different from those in the United States: tips are not necessarily expected for restaurant service, but for help with directions, with making a large purchase, or with loading bags onto a bus, a tip, or “dash” is expected. (“Dash” functions as both a noun and a verb.) Often, the services you are expected to dash for are services you don’t even want, and the tipper may even give money just to get someone to go away. The role of guilt in tipping is compounded in these situations by the uncertainty foreigners may have regarding tipping norms and by the income disparity between the average foreigner and the people who do these types of jobs in Ghana. The trouble with this is that the efficiency of the tip is further diminished. While guilt may make me a generally good tipper, as an economist, I also feel guilty when I tip for poor service or services I don’t want, thus providing poor incentives. Here is my advice on tipping in Ghana to maximize good incentives: Restaurants: Tipping is not mandatory for food service, though it becomes more expected the more upscale the venue. I highly recommend giving small tips/dashes that are very sensitive to the quality of service. At a local eating spot, 1 GHS is a good tip for basic service, and will likely get you a little extra attention next time you visit. At a nice restaurant in Accra, a 10% tip for good service seems to be well-received. The rarity of tipping in Ghanaian restaurants presents an opportunity to tie tipping to good service, so I would urge varying tips accordingly, giving nothing for poor service, and large tips for good service. Bags: If someone helps you carry your bag, it is very much expected you will give a dash. If you don’t want to, then be firm about carrying your own bags. Bus baggage: Small dashes are often expected for loading your bags under a bus. It is hard to avoid using this service. This is the context where I have found demands for dashes to be most outrageous. A dash should not be mandatory for this—I have seen supervisors yell at men who demanded a dash before loading bags. I would recommend resisting anyone who demands one before helping you. The dash should also not be large. I once encountered a man who refused my 1 GHS dash and demanded 2 GHS. I gave him nothing. I would not give more than 1 GHS unless your bags are many, or you receive some special assistance with them. Note that a dash for loading should not be confused with an actual fee for baggage. Directions: You should not have to pay a dash for directions. If someone walks a long way with you to show you where something is, a dash may or may not be demanded. If you don’t want to give one, don’t accept the escort. Assistance with purchases: If someone helps you locate, select, bargain for, and complete a substantial purchase, a dash may be in order. Things to consider: how much help you received, how much time and money you saved as a result of the help, and whether the person got any financial gain from your purchase. Generally, anyone who approaches YOU about buying something doesn’t need a dash. Household errands: If you have a guard or groundskeeper, the person will often run errands for you. You should dash to compensate for their travel costs and efforts. Professional services: Professional services outside a person’s normal job may require a dash, depending on the job and the organization a person works with. As an example, I had a document notarized by a judge in Tamale, and I paid a 5 GHS dash for his time and trouble. Stealth window washing: One of the strangest things about Accra are stealth window washers, who swoop in on a car waiting at an intersection, squeegee the front windshield despite the driver’s protests, and then demand a dash after. No matter how guilty you feel, please, please do not dash for this or other unwanted services that are forced on you; you will only encourage the practice. Further advice on tipping in Ghana (or anywhere else)? Please contribute in the comments! In the United States, one says, she is pregnant BY him...

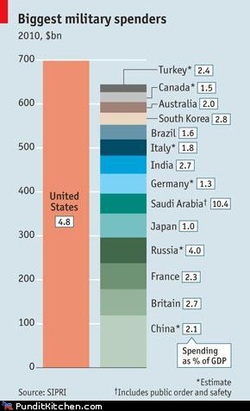

In Ghana, one says, she is pregnant FOR him... This may be simply a random twist in syntax, but to me the different prepositions carry different connotations. To be pregnant BY someone seems more to imply that the man is the subject and the woman the object, while to be pregnant FOR someone seems to imply more agency on the woman's part; she is the subject and he the object. In addition, to be pregnant FOR someone suggests that a woman is doing a man a favor by carrying his child. I'm warming up to the use of "FOR" in this case. Military spending by the top military spenders, from the Economist.

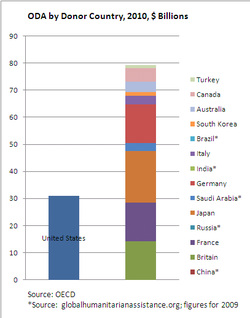

What if we replace military spending with official development assistance for these same countries? This weekend, after a delicious dinner, some friends and I visited a rooftop drinking spot in Osu. As I slowly drove my motocycle into the crowded parking lot, a man reached out, put his hand on my leg, and slid his hand up my skirt as I went by on the moto. It took me a moment to register what had happened, and by that time, I had passed the group of men, and wasn’t even sure who had done it. After fuming for several minutes, I joined my friends, had a double whiskey, and did my best to forget about the incident and enjoy the rest of the night.

As I write this, several days later, I am still furious—furious with the man, but more furious with myself for failing to give the man any disincentive to repeat his actions. The options were many: yell at the man; report him to the police; hit him; run over his foot with my moto; or in my most vengeful fantasy, castrate him with my moto keys. Why didn’t I do any of these things? It wasn’t that I am incapable of standing up for myself. For the most part, it was simply because I wasn’t quick enough to react, but riding away had its advantages: I wasn’t physically hurt, I got out of a potentially harmful situation quickly, none of my friends had to be involved in a mess, and I was able to move on and continue my night. It’s hard to imagine a better outcome had I chosen to confront the man—but at what cost did this efficient short-term result come? What does it take to prevent this type of behavior? Minor physical assault and sexual harassment is not uncommon in Accra. My recent experiences include: · A man grabbing me around the waste and pull me away from my friends to try to get him to dance with me at an outdoor dance spot. I peeled him off of me and started yelling at him; another Ghanaian intervened and convinced him to leave us alone. · A man repeatedly came up to my friends and me in a dance club and rubbed against us, even though we were not dancing. After asking him three times to stop, I told him to “F-k off” and shoved him. He drunkenly fell on the ground and then went away. · A man on the street grabbed my hand as I was walking by him one evening and would not let go. I dug my keys into his wrist as I twisted my hand free. He let me go on my way. Let’s be frank—women face these types of encounters everywhere. I have a close friend in New York for whom catcalls are a humiliating but regular part of her daily commute. She has experimented with every type of reaction I can think of: anger, humor, honest conversation, and simply ignoring it. Nothing seems to make a difference. Is a man with a key gouge on his wrist less likely to try to grab a woman’s arm than one who got away unscathed? The truth is, I don’t think any reaction from a victim of harassment is enough disincentive to put a stop to this behavior. To be an effective deterrent, punishment must come from broad society. Men who sit on steps and catcall in New York City should face the disapproval of the grandmother next door and the scorn of the respectful men who pass by and see them as the boys they are. Men who assault women in Accra bars and clubs should be unwelcome in those spots, and those who grab women on the streets should be ostracized by other vendors there, who face lost business when women avoid those spots. In some cases, this happens. Too often, it doesn't. As long society fails to punish men for this behavior, a they will continue to bet that victims won't punish them either. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed