|

I was visiting microfinance groups again. Today's group was just about to receive their first loan.

While discussing the community, the group had an interesting complaint: a man in the neighborhood, noting soil erosion and worrying that his home would be affected, bought--as in paid for-- a truckload of trash and had it dumped on the eroding slope. I should note that buying garbage here is just absurd, because there is no garbage collection, so garbage sits around in piles until somebody burns it. The community was understandably upset at having a load of garbage dumped in the middle of the neighborhood, but when they confronted the man, he tried to start a fight. The microfinance organization plans to help the community complain to a local official, and hopefully they will convince the man there are more hygienic ways to prevent erosion.

1 Comment

Today I spoke with a woman who said she did not have health insurance because she had family members who would pay for her treatment if she got sick, but those same family members would not pay for her insurance premium. Unfortunately for the national insurance scheme, this sounds perfectly rational to me (at least from her perspective; not the family members').

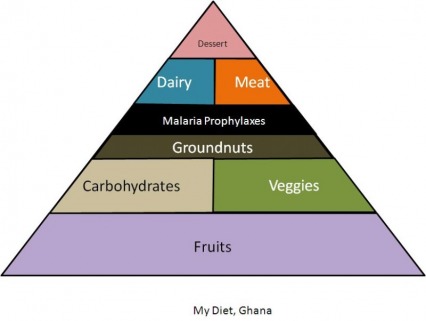

Another unfortunately rational decision: not re-enrolling each year. The way the scheme is implemented now, if you enroll once, but fail to re-enroll the next year, you get coverage immediately at any time by just paying the premiums you have missed. Many people only re-enroll when they are sick, and the treatment cost is more than the missed premiums. This makes perfect sense, so why would anyone do otherwise? As long as people can do this, this poses a problem for the sustainability of the scheme-- if the only people who are enrolling and paying premiums are the people who are getting sick, the scheme will never be able to finance itself. I am slowly adjusting to my Ghanaian diet. It is getting easier now that I have a working stove. I also finally found where to buy flour, and feel like a world of culinary opportunities have suddenly appeared! I am getting tired of bananas, though. One of the health care providers I visited today offered to sell me his hospital. I told him that we would not be able to run it as well as he could.

On the other hand, my organization has already acquired a monkey named George for 8 cedis (about $5), so why not add a hospital to our collection? I am spending this week visiting health care service providers in Tamale, in order to find out more about how Ghana's national health insurance works.

Ghana's national health care scheme is supposed to be open to anyone. The cost is low (although I am still trying to figure out the exact price; I suspect it varies by region), and some groups, including pregnant women and the very poor, get coverage for free. My first couple of stops were at pharmacies, and what I found out about how they deal with insurance was fascinating. Like Medicaid and Medicare in the United States, Ghana's national health insurance plan does not reimburse service providers at the same rate as private insurance, or the rate that would be charged to those with no insurance. The national health insurance may reimburse pharmacies at perhaps 75% of the market price for many drugs. To make up for this, pharmacies require patients to "top-off"-- to pay the difference between the market price and the insurance price. Although this difference may only be 25 cents or so, many people cannot afford it; those who are covered for free are usually so poor that they cannot buy food. Another alternative is for the patient to accept a smaller quantity of the drug, while the original quantity is reported in the insurance claim. (I'm not an expert, but I'm pretty sure that would constitute Medicare fraud in the United States.) Finally, in some cases the pharmacist will give the patient the medicine without requiring the top-off, and the pharmacy will take a loss on that transaction. The National Health Insurance Authority expects pharmacies to behave as health providers in the United States, and accept the prices they are given. However, Ghanaian pharmacies are required to accept insurance, and for many, a large share of their patients use the national health insurance. They could not survive on the prices set by the national insurance. I have heard that the prices are too low because the price list is not updated frequently. I do not know if this is true. Raising the prices will certainly make the already-struggling insurance scheme more expensive. It may be that a co-pay on drugs could even make sense. However, it will not work for the poorest of the poor, and pharmacies should not be alone in bearing the cost of providing medicines to these people at below market rates. Saturday night I attended a Ghanaian beauty pageant with some friends. The first thing I learned is that events here never start on time. The pageant was scheduled to start at 8; we got there at 9, and we waited an hour and a half before it got started.

The pageant was put on by the local technology school's marketing department; the contestants were students in the department. The pageant provided an interesting overview of local performance groups, as there were filler acts in between the pageant events. The pageant itself comprised a group dance, a talent portion, and a question and answer section. The talents were mostly dancing, except one contestant who acted out a dialog. Based on the quality of the various filler acts, dancing seems to be the highlight of the local performance arts. My favorite was the contestant who donned a fedora and did a Michael Jackson dance; another contestant performed a traditional dance that was quite good. The question and answer portion was the most interesting. The questions would have fried the brains and nerves of any U.S. pageant contestant. Here were a few of them: 1. What do you think about female genital mutilation? 2. If your 10-year-old sister were raped by your uncle, what would you do? 3. Imagine that the day before your wedding, your fiancé finds out he is HIV positive. What would you do? 4. Do you think Ghana's domestic violence law is effective? The contestants gave short but well-reasoned answers, and did not seem at all phased by them, while I and the other ex-pats were stunned at their intensity. I think this underscores how sheltered our lives are in the U.S.; these issues are realities for many young women in Ghana. In the end, the winner was contestant number 6. Apparently the judges' taste differed from mine, because I had not been especially impressed with her talent or answer. I was sad that the MJ girl did not place. However, my friend's host brother was delighted, because he had been smitten with her from the beginning of the pageant; the choice appeared to be popular with the crowd as well. All of the women were beautiful, talented and well-spoken, and should be proud of their academic achievement at the markas well. I am currently obsessed with change. Going to the market is an exercise in retaining as much small change as possible.

I was warned to jealously guard my one cedi notes and coins, but I did not realize how important this would be until I was trying to buy lunch the other day. I walked up and down the street, but no one could sell me fried cheese or avocados and give me change for my ten cedis. I was starved by the time I decided to go to the canteen and buy a full plate of jollof rice. Although my problem with small change is likely exacerbated by the disparity in income between me and most of the people living in Tamale (I take 100 cedis (about $70) out of the ATM at a time, where many people may earn only a few cedis a day), I believe the lack of small change is a problem for everyone. Many things are sold for less than 1 cedi, yet 10 cedi notes are prolific and coins are rare. I have heard there are businesses that will trade you 9 one cedi notes for your 10 cedi note. This problem may also be related to the recent re-denomination of the cedi; several years ago they chopped four zeros off the currency; what sold for 10000 cedis is now 1 cedi. Ghanaian food includes several dishes that are very accessible to newcomers. My favorite so far is red red, a dish comprising spicy tomatoes and beans served with fried plantains. Jollof rice, a simple fried rice dish, is also very easy to like. Beyond prepared dishes, a variety of very good tropical fruits and vegetables are cheap and easy to find on the streets, including mangoes, papaya, pineapples, bananas, and avocados.

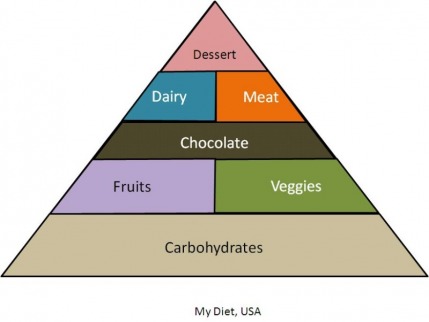

However, as is common when adjusting to a new diet, I am having cravings for a number of odd things, among them, tortilla chips, cherry pie, sweet and sour chicken, parmesan cheese, ice cream, and anything dairy—there is very little dairy here. I have heard that lactose intolerance is common here, but I do not know if this is true. I am used to drinking milk and eating cheese and yogurt regularly, so dairy cravings are not unexpected. I know from experience that eventually I will adjust, and start craving locally available foods, but till then, expect facebook updates professing my desperate desire for red bean buns. I’ve been in Tamale, Ghana for 15 days now. This is my first blog post since I’ve arrived, for several reasons. First, I haven’t had good internet access until now. Second, the website I use to blog, Weebly, blocks access from Ghana. Their explanation is that users in Ghana have set up a large number of fraudulent websites. Happily, however, since I was an existing user, Weebly was willing to make an exception for me so that my account could be accessed from Ghana.

Tamale is actually a lot like my hometown of Clarkston, WA. It is the center of a poor, rural agricultural area, and the town is about the same size as the Lewiston-Clarkston metro area. The air quality is bad, because most people burn their garbage. Religion is an important part of life. In Tamale, people speak of shopping in Accra with the same reverence Clarkstonians reserve for shopping in Spokane. Public transportation is much better in Tamale, though. My life since I have been here has been a mix of surprisingly modern conveniences and a surprising number of challenges in obtaining and maintaining those conveniences. I arrived just as IPA was moving into a new office and a new house for its employees, which means that I am lucky to have really nice places to live and work, but I am also experiencing the glitches that come with moving. We still do not have internet at the office, and we just got our furniture delivered there. At the house, I have electricity, a western-style shower and toilet (I even have hot water!), a propane stove, and fans in three rooms. However, since I have been here, the toilet tank has overflowed twice, we have had the stove fixed four times, and the other day half of the electricity went out. (Literally—some lights worked, others didn’t; my fan would only go half speed, and one of the overhead lights was even on on one end and off on the other. Our place must have some interesting wiring.) The takeaway from all this is that in places like Ghana and Senegal, you can have a life very similar to what you might in the United States—it’s just a lot more trouble to get it. I am only beginning to scratch the surface of Ghanaian culture, and I while the advent of internet is helping me to move forward with work, I still feel that I am just starting to get my feet wet. As my life here progresses, I hope to have a lot of interesting stories, observations, and insights for you. I miss you all, and I hope that you will keep in touch by email, Facebook, or replies to my blogs over the next two years! |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed