|

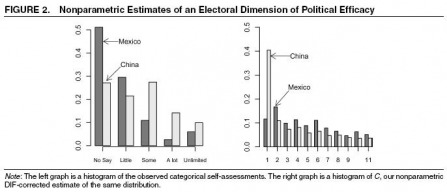

Today I attended a World Bank training on survey methods in developing economies. (I would just like to say, the World Bank has great food, and where do they get their papaya, because when I buy papaya here it always tastes funny.) One interesting bit of the training seminar had to do with calibrating surveys to adjust for differences in perceptions or attitudes among respondents. To get a more concrete idea of the problem, imagine asking two people to rank their health from 1 to 10. The first person is a young, Olympic athlete with a cold and sprained ankle, who rates her health as 5. The second is an old, barely mobile man who had a good day and was able to do a lap around his building with his walker. He ranks his health as 8. Is he really more healthy than the athlete? No, but the respondent's relative baseline matters. An example from actual research: Gary King, Christopher Murray, Joshua Salomon, and Ajay Tandon asked survey respondents in China and Mexico to rate their ability to participate in governance. Chinese respondents, on average, ranked their political efficacy higher than Mexican respondents. Few people would really believe that citizens have more political efficacy in China than Mexico. More likely, what Chinese citizens considered to be a "high" level of efficacy was different from what Mexican citizens considered to be a "high" level of efficacy. The researchers devised a way to account for differences in the respondents' relative baselines. They used vignettes, or stories illustrating a particular level of political participation, and asked respondents to compare themselves to the hypothetical. Using this method, Chinese respondents ranked their political efficacy lower than Mexican respondents, on average. Similar use of hypothetical vignettes can be used in surveys on other topics, including health, access to resources, education, etc., to ensure that respondents interpret questions similarly, and that their responses have the same meaning.

0 Comments

The Federal Reserve posted profits of $52 billion in 2009. The abnormally high profits were due to extra interest on assets held by the Federal Reserve; the Fed increased its balance sheet substantially as a result of its efforts to combat the financial crisis. Some of the extra interest came from increased holdings of Treasuries; some came from loans the Fed gave to bail out financial firms. After paying for its operating expenses, the Fed returned $46 billion of its profits to the U.S. Treasury.

PS. Hope I spelled "seigniorage" right. Microsoft Word, in its great wisdom, keeps suggesting "senior age". According to this post on the Freakonomics blog, when men and women ride in the car together, the man is much more likely to drive, even in households that consider themselves to be feminist. It's not clear why this is. Do men prefer to drive? Do women prefer to ride? Are men more likely to own the car?

Perhaps it is because women are worse drivers than men? Surprise! Stereotypes to the contrary, women are actually safer drivers than men. This is especially true among young adults. Don't believe it? Why do you think insurance premiums are higher for men? In fact, one study found that more testosterone leads to more bad driving in men: men with longer ring fingers (an indicator of more exposure to testosterone in the womb) had more traffic violations. So guys, do your part for feminism and lower health care costs: let her drive half the time! Plus, then you can play with the on-board computer. Because everybody knows women are worse with technology than men... |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed