|

A 20-year-old recently became internet famous for punching a man who joked about raping a drunk girl on the street one night. When is it ethical--and more importantly, efficient-- for individuals to take justice into their own hands? This question is particularly salient in Ghana, where vigilante justice is a common response to crime, and that justics goes up to and includes death for perpetrators of rape or severe property crime.  Actually, I did see what you did there. And I have a machete. Justice generally serves two economic purposes: to make an injured party whole, and to provide a disincentive against bad behavior. Vigilante justice tends to be focused on the latter. If you doubt this, just wait for the next Batman movie-- I guarantee my dear Bruce Wayne will wreak more economic havoc as the caped crusader than he will provide in redress. Vigilante justice comes at a high price, to the executioner, society, and to innocent parties who fall mistakenly fall victim to it, and is limited in the benefits it can provide.

In order to be justified then, vigilante justice must have a very high deterrent benefit. This will generally only be the case when legal justice systems completely fail to act as deterrents to morally reprehensible acts. It seems to me that the woman's decision to punch the rape joker fits this criteria. No court in the United States would ever provide any kind of consequence for comments like this man made. To me, the welfare gain from the chilling effect (amplified by publicity) this will have on such jokes, which quickly turn a fun night out into a stomah-clenching affair that can haunt a woman for months (if not years), clearly outweigh one guy having a sore nose for a couple weeks. Similarly, in Ghana, legal remedies are a poor deterrent to crime. (Especially legal remedies that are actually legal, NOT including police beating suspsects.) Even in clear cases where suspects are caught red-handed with eyewitnesses present, criminals often walk free. Two friends of mine were beaten with bricks a couple years ago, and one of the assailants was captured at the scene of the crime, but was released after several months of courtroom circus. Death by beating, however horrific, not only provides a clear disincentive to crime but permanently removes a criminal from society. So can vigilante justice be morally and efficiently right? Yes. Does that mean it should go unpunished? No. The fact that vigilante justice can have a high cost for falsely accused victims means that executioners must have a disincentive to engage in vigilante justice unless they are sure of its benefitcs. Punishing, or potentially punishing, perpetrators of vigilante justice provides that disincentive. So the woman who punched the joker should be potentially liable for damages, and those who engage in mob justice beyond that necessary for defense should be liable under assault laws, to prevent vigilantes from risking targeting those not truly guilty. This may seem like a rather extreme position; it is certainly influenced by living in situations where law enforcement seems ineffectual. However, the truth is, society engages in vigilante justice all the time. In the U.S., however, it is usually psychological, not physical: when someone cuts in line, they are often shamed, but not punched. Vigilante justice is an appropriate response to those inevitable situations where the law has no reach, but how it is exercised must be limited by disincentives against its most extreme forms.

7 Comments

The Ghanaian communications regulator fined five Ghanaian telecom companies a total of 1.2 million GHC today for providing poor quality services, a move sure to be popular with pretty much everyone, since people in Ghana love their phones and hate all the phone companies. To give you an example of what poor services means, I haven't been able to call or text anyone on MTN, or receive calls, since I arrived in Sunyani yesterday-- and it was like that all over Brong Ahafo when I left last week. This isn't some village in the mountains-- Sunyani is a district capital. The fines were based on failure to provide coverage, geographically and temporally. The highest fine went to Airtel, which has actually provided pretty reliable services for my internet modem, including the hookup to write this article. In my opinion, the highest fine should have gone to Vodafone, for their atrocious service. Vodafone is the only provider of cable internet in Tamale, and has the only nice, reliable internet cafe. When home and business internet lines go down, they never come fix them, despite repeated calls requesting they do so. Why should they? They can keep charging the monthly rate, plus get additional income when people are forced to go to the internet cafe. This is why natural monopolies must be regulated. The G20 summit meeting recently concluded in Pittsburg. The summit resulted in approval of a"Framework for Strong, Sustainable, and Balanced Growth". The framework includes acknowledgement that stimulus spending is needed in the short run, but that countries need to develop exit strategies to withdraw fiscal and financial sector support. The G20 also agreed to give developing economies more ownership in the International Monetary Fund.

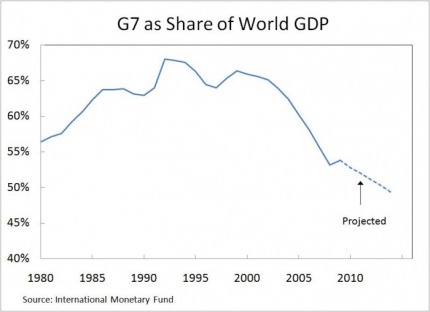

Some G20 participants, as well as commentators, suggested that the G20 should replace the G7 as the most important forum for coordinating international economic policy. What is with all these Gs, and what do they do? Here is my quick list of important G- summits, and their members: G7: This is a meeting of the finance ministers of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. G8: This is a meeting of the heads of state of the G7 countries, plus Russia. Fun fact: after shirtless pictures of Sarkozy and Putin emerged a couple years ago, snarky journalists suggested a "G8 calendar". G20: This is a meeting of finance ministers and central bank heads from 20 countries, including the G8 countries, Australia, whichever country is the current president of the EU (provided that country is not already included), and 10 large emerging market economies: Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey. G2: Not really an official designation, this is sometimes used to refer to China and the United States. The idea is that agreements between these two countries could become necessary and sufficient to drive international policies. Besides generating fun photo ops, the G7, G8 and G20 meetings allow countries to meet to coordinate policy on security, economics, and the environment. The efficacy of these meetings is limited by the fact that the members are sovereign nations, so any agreements that might be reached are only worth as much as each nation's commitment to hem (and domestic political realities!) While the G8 may retain importance on security, in part because of the difficulty in coordinating policy among 20 countries, it is very likely that G20 will indeed become the more important forum for economic policy-- it seems bizarre to discuss the global economy without China, and developing economies are becoming a larger share of the world economy. The IMF projects that the G7 share of world GDP will drop below 50% in 2014, down from near 70% in the early 1990s. Final fun fact: At summits such as the G7 or G20 summits, the person who in charge of the meeting for each country (who develops materials, schedules officials' participation, etc.) is called the "Sherpa". (They help you up the summit, haha, get it?) Borrowing from the culinary world, the Sherpa's deputy is known as the Sous-Sherpa. Treasury Secretary Geithner testified at the House Financial Services Committee again today, underscoring the need for financial regulation reform. Nothing new was proposed, but Secretary Geithner reiterated the Administration's proposals and urged quick action on reform.

Chief among the proposals are: 1. The formation of a consumer protection agency that would regulate all financial services; including credit cards and mortgage brokers 2. Merging the Office of Thrift Supervision and the Comptroller of the Currency into one national bank supervisor; 3. Increasing the Federal Reserve's powers to regulate bank holding companies like Goldman Sachs 4. Creating a board with representatives from all the regulators to look for systemic risks and coordinate financial oversight policies 5. Increasing capital requirments and other regulations on large, "too big to fail" financial institutions, and using ex posts taxes on large financial firms to recoup the costs of any future bailouts The strategy for finacial regulation reform is to try to pass individual pieces of legislation addressing each issue. Some of these items will be easier to achieve than others. House Financial Services Republicans agree on the need for increased consumer protections and an over-arching body to look at systemic risks and coordinate regulatory policy among agencies. They differ on the future role of the Federal Reserve and on dealing with insolvent firms. Republicans propose stripping the Federal Reserve of all of its regulatory powers, and giving them to the national bank supervisor. The also propose a policy of no bailouts, even for systemically important firms. Both of these proposals seem rather radical (and very unlikely to be implemented with a Democratic House, Senate and Administration), and it is likely they are designed to pander to anti-Fed and anti-bailout sentiment in voters. Most of the Democratic proposals seem like reasonable responses to some of the problems that contributed to the financial crisis. However, I wonder about the plausibility of the plan to recoup bailout costs ex post. In a wide-spread financial crisis, where many or most large financial firms take large losses, an ex post tax could be a significant burden on the remaining (and as evidenced by their continued existence, the most prudent) financial firms as they attempt to recover. A thought that occurs to me-- which I am sure will be unpopular-- : in a situation where the risk was as widespread and systemic as it was in this crisis, not all of the blame rides on large financial firms. Many individuals benefitted from cheaper credit prior to the crisis; credit that was, in retrospect, too cheap. No regulations can foresee all future crises, and it is in part the responsibility of the government to adapt to evolving financial markets and address new systemic risks that arise. Perhaps when the government fails at this, it should bear part of the cost of fixing it. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed