|

Clearly, the nations of the world are not going to line up to let me randomize their monetary policy. But what if I could convince one to do so?

Randomized control trials (RCTs), when ethical and possible, present the most reliable way to measure the impact of policy. Units of randomization, for instance people, are put into a treatment group, who gets a program or policy, and a control group, that doesn't get the program or policy. You compare outcomes for the two groups to see the impact of the program. The key to the validity of the RCT is that the sample size has to be big enough that when you randomly divide into treatment and control, there are no important systemic differences between the two groups. Randomization isn't used to evaluate macroeconomic policies for 2 reasons: 1) it is usually too important for people to allow it to be randomized, and 2) it has to be enacted at a high level-- national or maybe state or province-- so it is difficult to get a large enough sample. But what if we randomized, not by entities like people or countries, but across years? For example, what if the Federal Reserve allowed me to randomly change the policy interest rate by +25 basis points, 0 basis points, or -25 basis points? Over a long enough time frame, the periods that fall into each randomization group should be statistically the same on average. This would allow us to look at the effect of the interest rate change on the economy. Of course, there are some kinks to be worked out. Similar to spillover effects, policy changes have impacts across multiple periods; however, these could be measured and accounted for. Another problem is checking the balance of the randomization. There would be no equivalent to a baseline, and you couldn't stratify, since you don't know the attributes of future time periods in advance. These problems would imply that you need a very large sample size. There are certainly other methodological challenges I haven't thought of. I imagine I will have plenty of time to think through them before the first problem-- the fact that politicians, who insist they can control things they can't, would never randomize something they can-- is solved. But if anyone hears about a central bank looking for a monetary policy consultant, let me know.

13 Comments

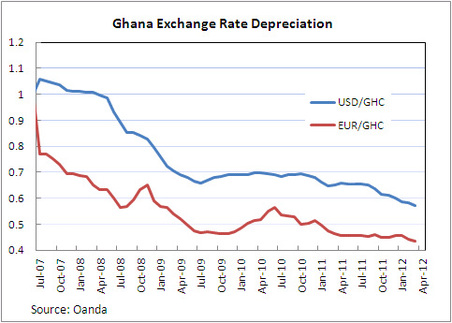

The Ghana Cedi has depreciated noticeably in recent months. Similar depreciations were seen in 2000 and 2008, which, like 2012 were election years. (In 2004, also an election year, the cedi did not depreciate much.)  By the way, the actual currency code for the Ghana cedi is GHS. GHC refers to the old cedi. International finance nerds love currency codes. Does the Ghana cedi experience election year blues? If so, why? To address this question, I examine a few alternative explanations for the depreciation of the cedi: 1. The cedi depreciates in election years due to uncertainty about Ghana’s political and economic future. Uncertainty could result in cedi depreciation if it leads investors to pull their money out of Ghana, or to hesitate to invest in the first place. With the lead-up to the election looking more tumultuous than previous elections, and recent unrest in other West African countries, it would seem investors have reason to be cautious. It’s hard to find data to test this theory right now, as foreign investment data usually come at a lag. Foreign investment was strong in 2011 compared with 2010, but that says little about developments in the last half year or so. Uncertainty could also lead to depreciation if the cedi falls under speculative attack. The Bank of Ghana has attributed some of the depreciation to speculation that drives down the value of the cedi. (http://www.bog.gov.gh/privatecontent/MPC_Press_Releases/50th_MPC_Press_release-_Final_Copy.pdf) 2. The cedi depreciates in election years due to politically-motivated expansionary monetary policy by the Bank of Ghana. The incumbent party would benefit from a strong economy come election time. Short-term economic growth can be encouraged through expansionary monetary and fiscal policies. Increasing the money supply, however, eventually leads to inflation, which hinders the economy. The Bank of Ghana has actually raised policy interest rates in recent months, but you can’t necessarily look at policy interest rates alone to see if monetary policy is expansionary. Here’s why: the government of Ghana has been spending a lot of money (typical of an election year.) Normally, this would push up the government’s borrowing costs, and raise interest rates generally. However, if the central bank keeps rates constant rather than letting them rise, this has an expansionary effect. A better measure to look at is inflation. One-year inflation rates appear to be pretty steady, but these do not reflect very recent trends. The trouble with looking at monthly inflation is that prices in Ghana are highly seasonal, rising in the spring and then falling after harvest, and seasonally adjusted series are not released. Inflation in January and February was only somewhat higher than inflation in those same months over the last few years. While the key statistics that would be indicative of expansionary monetary policy are inconclusive at this point, the Bank of Ghana does acknowledge some other indicators of looseness. The Bank mentions that credit has eased, meaning money is easier to get, and that starting in 2011, there have been signs of liquidity overhang—meaning that banks have more cash than they want, causing interest rates to fall. The Bank mentions that these lower interest rates on cedi assets could be driving investments to other currencies with a higher rate of return. 3. The cedi depreciation is only coincidental to the election year, and is driven by other factors, including global economic conditions. There are some other factors that could be driving cedi depreciation. The first, mentioned by the Bank of Ghana, is that the depreciation is driven by demand for foreign currency to buy imports. Despite strong exports of oil, gold and cocoa, Ghana’s imports are growing faster than exports. A second possibility is that economic trouble in Europe is having a negative impact on the funds that are available to go to Ghana. This could account for a decline in investment in Ghana, if indeed such a decline is occurring. Remittances, however, appear to have remained robust, according to the Bank of Ghana. So what do I think? I think it is possible the election is having an effect, either on foreign investment, or on speculation in the currency market. I also think that the Bank of Ghana’s policies, politically motivated or otherwise, are responsible for it. While political turmoil is hard to address, a central bank can easily punish speculators and attract investors by raising interest rates. It appears that the Bank of Ghana is now taking steps to do just that, but earlier action might have nipped the depreciation and any speculation in the bud. My guess is that growing imports and a stagnant global economy may play roles, but not central ones. The West African CFA Franc, for example, has actually risen against the dollar since the beginning of the year. This suggests that at least some of the cedi’s downward trend is specific to Ghana’s. Luckily, that means that Ghana has the power to change it. The Council of Economic Advisers has released the 2010 Economic Report of the President. You can find a link to the full report, as well as a summary of the highlights, here.

Quick summary: The economy was a mess when President Obama came into office, because of problems that were a long time in the making, including stagnating middle class incomes, rising health care costs, and flawed and under-regulated financial markets. The economy is still not great, with a slow recovery and lagging job formation expected, but it is in better shape than it would have been if the stimulus bills had not been implemented. We should still do more. Pass jobs support and health care reform now! According to NPR, this is the brainchild of Spike TV producer John Papola and libertarian economist Russel Roberts, together with rap duo Billy and Adam.

I just came across this rather wacky article about how buying holiday gifts is bad for the economy: http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Investing/top-stocks/blog.aspx?post=1498404&_blg=1,1498404. Is this true? I will recap the main arguments, and tell you whether they are true or false.

#1. Gift-giving is inefficient. True. The economic paper The Deadweight Loss of Christmas theorizes that when you buy someone a gift, it is likely that if they had had the money instead, they would have bought something different. This means that your gift is less efficient than just giving them the money. However, the paper also points out that gifts can actually be MORE efficient in some instances-- for example, because the item is a gift, it may have sentimental value beyond its purchase price. However, the main problem with this argument is that it confuses microeconomic efficiency with macroeconomic benefits. If consumers spend more as a result of gift-giving than they would if they only bought items for themselves, then this is good for the macro economy, and good for creating jobs. #2. Consumption is less of the economy than we think, because the middle steps of production aren't counted. Bizarre. I don't think the author understands the concept of GDP and how it relates to consumption at all. GDP is the total value of everything produced in the United States. You can't count the middle steps, because that would be double-counting. We count GDP by measuring the four things that we can do with what we produce: consume it, invest it, import it, or use it in the government. Those four things drive demand for our goods and services. Yes, there are middle steps-- but no one would pay people to cut lumber for couches if someone wasn't eventually going to buy the couch. So when economists say consumption is 70% of the economy, consumption really is 70% of the economy-- or at least it drives 70% of it. #3. Consumer confidence is misleading because the survey only asks 6 things. False. Complain about how many questions there are all you want, but the consumer confidence indices that come out of those questions have shown themselves to be accurate reflections of how the economy is behaving. Next time you want to complain about an indicator, show me evidence that it contains no information. #4. The seasonal upward trend in the stock market isn't due to gift shopping. Who cares? There is no reason to expect it would be. Market participants know that consumption goes up in December, so that would already be built into prices. Stock prices might rise if retail numbers were much stronger than market participants expected (or might fall if they were weaker.) But none of that is a reason that gift shopping is bad, if gift shopping raises overall consumption. There is a real reason gift-giving can be bad: we can't afford it. If purchasing gifts drives consumers into debts they would not otherwise have, it is probably not good for individuals. It may be bad for the United States as a whole as well, since low saving is a driver of the trade deficit. However, if you can afford it, and you feel so moved, don't be a Scrooge-- go buy that gift and encourage job growth! The G20 summit meeting recently concluded in Pittsburg. The summit resulted in approval of a"Framework for Strong, Sustainable, and Balanced Growth". The framework includes acknowledgement that stimulus spending is needed in the short run, but that countries need to develop exit strategies to withdraw fiscal and financial sector support. The G20 also agreed to give developing economies more ownership in the International Monetary Fund.

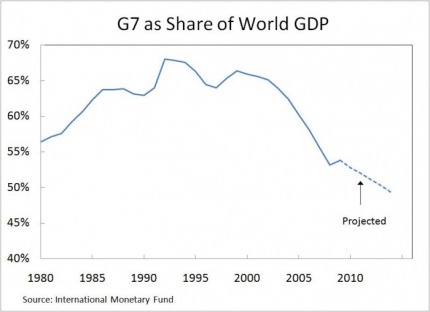

Some G20 participants, as well as commentators, suggested that the G20 should replace the G7 as the most important forum for coordinating international economic policy. What is with all these Gs, and what do they do? Here is my quick list of important G- summits, and their members: G7: This is a meeting of the finance ministers of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. G8: This is a meeting of the heads of state of the G7 countries, plus Russia. Fun fact: after shirtless pictures of Sarkozy and Putin emerged a couple years ago, snarky journalists suggested a "G8 calendar". G20: This is a meeting of finance ministers and central bank heads from 20 countries, including the G8 countries, Australia, whichever country is the current president of the EU (provided that country is not already included), and 10 large emerging market economies: Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey. G2: Not really an official designation, this is sometimes used to refer to China and the United States. The idea is that agreements between these two countries could become necessary and sufficient to drive international policies. Besides generating fun photo ops, the G7, G8 and G20 meetings allow countries to meet to coordinate policy on security, economics, and the environment. The efficacy of these meetings is limited by the fact that the members are sovereign nations, so any agreements that might be reached are only worth as much as each nation's commitment to hem (and domestic political realities!) While the G8 may retain importance on security, in part because of the difficulty in coordinating policy among 20 countries, it is very likely that G20 will indeed become the more important forum for economic policy-- it seems bizarre to discuss the global economy without China, and developing economies are becoming a larger share of the world economy. The IMF projects that the G7 share of world GDP will drop below 50% in 2014, down from near 70% in the early 1990s. Final fun fact: At summits such as the G7 or G20 summits, the person who in charge of the meeting for each country (who develops materials, schedules officials' participation, etc.) is called the "Sherpa". (They help you up the summit, haha, get it?) Borrowing from the culinary world, the Sherpa's deputy is known as the Sous-Sherpa. A poll by Gallup and Healthways found that of all types of workers, those who own their own business tend to be happiest. Professionals were the next happiest. At the bottom, unsurprisingly, were those who worked in services, transportation, or manufacturing.

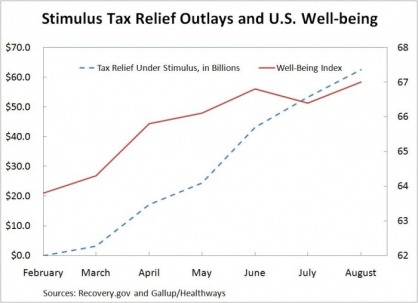

Interestingly, this same poll, which is collected on a monthly basis, shows that for the entire population, perceptions of well-being jumped considerably this spring particularly in April-- the same time that stimulus spending started. I'll admit this is likely a bit spurious, and improved optimism during this time probably reflected a generally improving economy. Still, I've heard shoddier arguments for and against the effectiveness of stimulus. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed