|

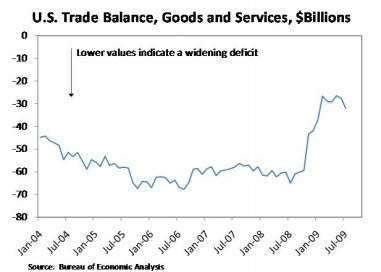

The U.S. trade deficit has been trending up over the past year, and the goods deficit is now at the highest level since November 2008. While a large and persistent trade deficit is not a good thing for the American economy, the recent trend should not itself be particularly alarming: at this point, we are merely retracing declines in the deficit that came as a result of the economic downturn. The recent increases in the deficit can be seen as symptoms of an improving U.S. economy that is consuming more goods and services, and importing more to meet that demand. That said, we should consider how we are funding this increase in imports. The last two expansions in the trade deficit corresponded with asset bubbles: the tech bubble and the housing bubble. U.S. investment outpaced U.S. saving, and foreign investment made up the gap-- and the influx of money enabled the United States to buy more from abroad. Where are we getting the funds to increase our imports now? Part of the answer may be that households are consuming more and saving less (savings rose during the recession), but another source may be government debt. U.S. Treasuries fared well during the crisis, as investors turned to them in a flight to safety. If investment in U.S. government debt really is a driving force of the increase in the trade balance, this could be concerning, because, while we certainly don't want investment bubbles in any asset type, we should generally prefer to go into debt in order to increase future growth. Taking investment from abroad is great if it increases future growth in the tech sector; if it is fueling consumption that won't translate into future growth, it is concerning.

One could argue that the government stimulus policies are indeed an investment in future growth, because they have prevented a potentially devastating depression. However, as the economy starts to turn around, I think the United States will need to tackle the discrepancy between domestic saving and domestic investment and consumption. To note, Ghana is doing its part to help the U.S. trade balance: the U.S. is currently running a surplus with Ghana. Main exports include petroleum products, mining equipment, and cars. If you all will send some more Parmesan cheese this way, we can do even better!

0 Comments

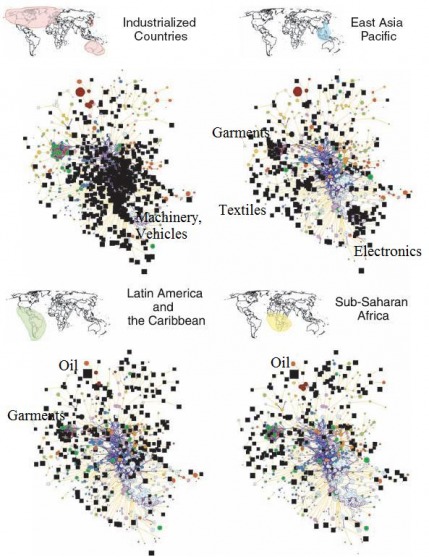

This paper isn't new, but I recently saw Ricardo Hausman give a presentation on it, and it is quite interesting. The basic premise is that the products that countries produce can be grouped according to the inputs required to produce those products. Knowing how products related to each other could help developing economies figure out what industries to focus on. It is easier to develop industries that share production inputs with products you are already making than it is to develop industries that require a completely new set of production inputs: it is easier for monkeys to swing to a nearby tree than it is for them to swing to a farther tree. The researchers used product categories and job categories to figure out how closely different products were related to each other in terms of inputs. They then looked at several sets of countries, and mapped which products they were producing. The diagrams above show the result of this exercise: the colored dots are products, the lines connect those products that share inputs, and the black squares show what each group of countries is producing. Developed economies produce goods near the center of the cluster. The goods on that part of the map are things like electronics, that require a lot of inputs, but share inputs with a lot of other products. Developing economies are at the periphery of the map, making goods with fewer inputs, and that don't share inputs with many other goods. The point: developing economies are less diversified (no surprise) and less flexible if their main product goes bust.

I've added labels describing important product clusters for each group of countries. Developed economies are clustered around high-value, complex product manufacturing. Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa both have oil as an important product. Asia has clusters in the areas garments, textiles, and electronics. This point about garments and textiles is interesting. Although it might seem obvious these should go together, they actually don't share many inputs. It's possible that the inputs, though not shared, have similar attributes. Perhaps they require workers with similar levels of education, even if the jobs those workers do are quite different. Or perhaps proximity matters: maybe it is cheaper to make fabric closer to where you sew it. Either way, it suggests targeting industries for development is even more complicated that the charts above suggest. I just came across this rather wacky article about how buying holiday gifts is bad for the economy: http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Investing/top-stocks/blog.aspx?post=1498404&_blg=1,1498404. Is this true? I will recap the main arguments, and tell you whether they are true or false.

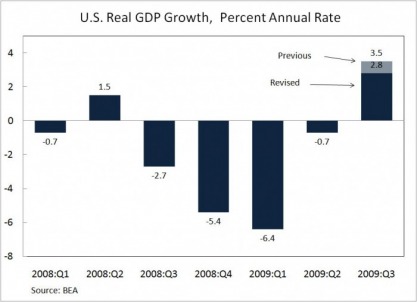

#1. Gift-giving is inefficient. True. The economic paper The Deadweight Loss of Christmas theorizes that when you buy someone a gift, it is likely that if they had had the money instead, they would have bought something different. This means that your gift is less efficient than just giving them the money. However, the paper also points out that gifts can actually be MORE efficient in some instances-- for example, because the item is a gift, it may have sentimental value beyond its purchase price. However, the main problem with this argument is that it confuses microeconomic efficiency with macroeconomic benefits. If consumers spend more as a result of gift-giving than they would if they only bought items for themselves, then this is good for the macro economy, and good for creating jobs. #2. Consumption is less of the economy than we think, because the middle steps of production aren't counted. Bizarre. I don't think the author understands the concept of GDP and how it relates to consumption at all. GDP is the total value of everything produced in the United States. You can't count the middle steps, because that would be double-counting. We count GDP by measuring the four things that we can do with what we produce: consume it, invest it, import it, or use it in the government. Those four things drive demand for our goods and services. Yes, there are middle steps-- but no one would pay people to cut lumber for couches if someone wasn't eventually going to buy the couch. So when economists say consumption is 70% of the economy, consumption really is 70% of the economy-- or at least it drives 70% of it. #3. Consumer confidence is misleading because the survey only asks 6 things. False. Complain about how many questions there are all you want, but the consumer confidence indices that come out of those questions have shown themselves to be accurate reflections of how the economy is behaving. Next time you want to complain about an indicator, show me evidence that it contains no information. #4. The seasonal upward trend in the stock market isn't due to gift shopping. Who cares? There is no reason to expect it would be. Market participants know that consumption goes up in December, so that would already be built into prices. Stock prices might rise if retail numbers were much stronger than market participants expected (or might fall if they were weaker.) But none of that is a reason that gift shopping is bad, if gift shopping raises overall consumption. There is a real reason gift-giving can be bad: we can't afford it. If purchasing gifts drives consumers into debts they would not otherwise have, it is probably not good for individuals. It may be bad for the United States as a whole as well, since low saving is a driver of the trade deficit. However, if you can afford it, and you feel so moved, don't be a Scrooge-- go buy that gift and encourage job growth! The preliminary estimate of GDP growth was revised down this week from 3.5% at an annual rate to 2.8%. While we'd clearly rather have the higher number, 2.8% is still pretty good compared with recent quarters.

What's behind the revision? New, better data indicate that personal consumption rose less than initially estimated. Also, imports, which don't count towards U.S. GDP, were a larger share of the increase in consumption. On the plus side though, exports rose more than the preliminary GDP report estimated. While the increased imports mean a lower estimate of U.S. GDP, they can still be seen as good news for our trading partners. I'm a little late on this one, but the World Economic Forum released its 2009 Financial Development Report in October. The United States, which was #1 in the rankings last year, has slipped to #3 this year, behind the UK and -- surprise!-- Australia.

Australia was #9 last year, but its relatively strong banking sector and economy have boosted it way up the list this year. How much does it matter that Australia is doing well? Australia isn't an extremely large economy. With a GDP of just over $1 trillion (exchange rate basis), it is the 14th largest economy, just after Mexico. That means that stronger demand in Australia has limited ability to help out the world economy. However, it is likely that Australia's economic strength is fueled by China's demand for the resources that Australia exports. And China, a much larger economy, has more scope to boost global demand. My roommate is currently driving a Dodge Charger rental while her beloved Hyundai is in the shop. She hates it.

Go figure. Consumer Reports put out their most recent reliability ratings, and Asian brands continued to dominate the best ratings; 36 of the 48 cars that received the highest reliability ratings were Asian makes (18 of those were Toyota.) On the bright side for American brands, Ford had several highly rated models, and some of GM's models did well too. Consumer Reports was able to recommend one Chrysler model, the Dodge Ram 1500 pickup, after recommending no Chrysler vehicles last year. In worse news for the American auto industry, GMAC (GM's finance arm) is reportedly in talks for a 3rd government bailout. The improvements in Ford and GM's ratings in Consumer Reports have been widely reported, but they are baby steps relative to the leaps and bounds the American brands will have to make to be on par with Asian automakers. One thing important to remember about the auto industry: much of the production of "foreign" cars is done on American soil, while a lot of the production of "domestic" cars is done in Mexico or Canada. The dire situation of domestic auto companies is bad news for Detroit, where domestic auto production was concentrated, but Toyota factories in California are cranking out Priuses (or is it Pri-i, like cacti?) and providing Americans with jobs. The Reserve Bank of Australia became the first G20 central bank to raise interest rates today, increasing its policy interest rates by 25 basis points to 3.25%. Of course, Australia has done very well through the financial crisis, relatively speaking. It's banks have remained pretty strong, China has continued to demand Australia's commodity exports, and Australia has only had one quarter of negative GDP growth. (Australia's real GDP fell 2.8% at an annual rate in 2008Q4. while in the United States, recessions are declared by the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee, many countries simply consider a recession to be in effect after two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth.)

The RBA's decision to raise interest rates resulted in a drop in the dollar. With Australia raising interest rates, investors know that there are assets out there where they can get higher returns, so low-yielding Treasuries don't look like such a good deal, despite their safety. The decision is also a vote of confidence in the world economy, which could increase investor's expected returns on assets other than Treasuries. As Australia and other countries (possibly Korea?) start raising interest rates ahead of countries like the United States and Japan, keep your eye out for a revitalization of the carry trade, where investors borrow in countries with low interest rates, and invest in countries with higher interest rates. On Friday, President Obama, acting on a recommendation from the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC), raised import duties on tires from China by a large margin. The increase will take effect September 26; duties will go from 4% to 35%. The additional duty will be phased out over the next three years.

The action came under Section 421 of the Trade Act of 1974, a section that was added in 2000 as part of the agreement that allowed China to join the World Trade Organization. Section 421, which applies only to China, says that the United States can impose import duties on Chinese products if they cause material market disruption in the United States. It is important to note that we don't need to show that China is engaging in unfair trade practices to use Section 421. (A number of commentators supporting the decision have misleadingly used the term "sanctions" to describe the action.) The United States has discretion in applying Section 421; President George W. Bush never applied the statute, despite the fact that the USITC issued several recommendations finding material disruption to U.S. industry from Chinese imports. (The first Section 421 case involved pedestal actuators, which lower and raise the seat of motorized wheelchairs. The USITC found disruption, but President Bush declined to impose tariffs, citing the added cost to disabled buyers of such wheelchairs.) President Obama is now the first President to impose tariffs under Section 421. So what will this do? Will it help American tire manufacturers? The markets seem to think so, as stock prices for Goodyear and Cooper bumped up today. Interestingly, however, neither of these tire companies supported the petition asking for tariffs under Section 421, which was filed by United Steel Workers. Here's why: these companies have outsourced much of their low-end tire production to China, so while the tariffs may cut down some of their competition, they affect them too. Consumers will almost certainly see prices of low-end tires go up. (High-end tire prices will be less directly affected, as production for them has remained in the United States.) Customers may have less choice in tires, until tire companies find alternative suppliers, either in the United States, or, more likely, in other countries with low production costs. China is understandably unhappy with the action, and is reportedly looking into ways to block U.S. exports of poultry and auto parts in retaliation. A full-out trade war seems unlikely, however, as both the United States and China understand the folly of such a war in this crucial period of economic recovery. Some analysts have attributed today's drop in the stock market to Friday's 421 decision. It is difficult to attribute stock market movements to particular events with any certainty, but even if the drop is related, it may not mean that markets expect a large negative fallout from this decision. Rather, it may reflect perceptions of the President's position on free trade, with market participants viewing this as a test case for future administration policy. Is anyone besides me tired of health care reform? You’ll inevitably get some health care postings from me, but for now, let’s switch to an entirely different topic. Let’s talk about how the trade deficit went up—and it’s a good thing!

In the shadow of last night’s health care speech, the Bureau of Economic Analysis this morning released July trade data showing that the deficit widened notably. Yes, we still have a large trade deficit, and yes, we’d prefer to have a much smaller one, but the increase in the deficit is largely symptomatic of improvements in the domestic economy. For the past year, we have seen the trade deficit narrow, as anemic domestic demand caused our imports to plummet. Slower global demand caused our exports to fall as well, but not as quickly as imports. The lower trade deficit was similar to a fever—it can help fight the sickness in the economy, but it is also indicative that something is deeply wrong (sorry, I guess I can’t help but think in health metaphors). July’s increase in the deficit was marked by a resurgence in both imports and exports, with imports growing more strongly, as the U.S. economy has picked up. Hopefully this will continue through the next few months, a sign the economy is on its way back to normalcy! |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed