|

After years of remaining a theoretical plaything for money nerds like me, nominal GDP targeting has suddenly become a thing. NGDP targeting has been getting love from economists across the political spectrum, which naturally means laypeople across the spectrum are responding with skepticism. Drudged up from what I remember from Prof. Burdekin's Money and Banking, I present the basics of NGDP targeting:

What is NGDP targeting? NGDP targeting means that the central bank sets monetary policy to target nominal gross domestic product, that is, GDP that is not adjusted for price level. The beauty of NGDP targeting is that since both prices and output are part of NGDP, both of these things influence monetary policy even though only one metric is considered. Either NGDP level, or growth, can be targeted. Why liberal economists like it: liberal economists tend to be more supportive of considering economic growth, not just inflation, when setting monetary policy. NGDP targeting naturally includes growth as an input. Why conservative economists like it: conservative economists tend to prefer simple, transparent rules for monetary policy, as opposed to opaque systems that give broad discretion to policy makers. NGDP targeting is easy to understand and easy to see if policy makers have met their goal. So how is it different? The Federal Reserve has what’s called a dual mandate—they are charged with considering both prices and economic output when setting policy. (Some central banks, like the European Central Bank, are charged with only considering prices.) The Federal Reserve does not commit to following any particular formula for setting monetary policy, but it is largely believed to behave as if it follows the Taylor Rule, meaning it considers deviations from target inflation rates and target employment rates. Targeting NGDP would provide the Federal Reserve with a mandate to specifically target deviations from output targets. There are other things a central bank can consider besides prices, employment, and output when setting policy, such as money growth and asset prices. A central bank with broad discretion can consider all of these things, but this comes at the cost of making monetary policy decisions less transparent. But what about QE2?? So where do things like quantitative easing fit into all this? It is important to distinguish between the tools used to set monetary policy and the tools used to implement monetary policy. Tools used to set monetary policy, such as Taylor Rules, money growth target, or NGDP targeting, tell the central bank whether they need to tighten or loosen policy. The tools used to implement monetary policy generally remain the same regardless of what policy prescription tool you use. If interest rates are at zero, and inflation is low and unemployment high, you need quantitative easing to get to your targets. If interest rates are at zero and NGDP is below target—guess what, you still need quantitative easing to get to your target. Targeting Growth vs. Level If you are going to target NGDP, you have to decide whether to target NGDP growth rate or NGDP level. Most of the cool kids in economics prefer level targeting. Level targeting has the benefit of allowing for catch up periods: after the economy has had a downturn, it natural that it have a period of both higher growth and inflation to catch up to where it would have been pre-downturn. So let’s do it? To me, whether NGDP targeting should be implemented actually involves three different questions: 1. Should GDP be considered when setting monetary policy? The downside to considering GDP or other factors is that the central bank places less weight on price stability, which is bad if you are an inflation hawk. The benefit is that drops in GDP often lead drops in inflation or unemployment, so considering GDP can help the central bank adjust to new economic trends more quickly. 2. Should the central bank target levels rather than growth rates? When it comes to prices, levels are arbitrary—it’s change in prices that matter. That’s the primary logic behind targeting inflation rather than price level. However, as discussed above, it is natural for an economy that has been sluggish for a while to have a period of higher growth and higher inflation to “catch up” after a downturn, so monetary policy that accommodates this can make sense. This accommodation can actually help end a downturn more quickly—if during a downturn, people know they can expect extra high inflation in the future, they have an incentive to spend more now, stimulating the economy. The flip side to all this, which I haven’t seen discussed much, is that monetary policy lags the trends a bit. This sounds great when you are coming out of a recession, but what about when you are coming out of an expansion? Would the people keen to see accommodating monetary policy continue as growth picks up be equally keen to see tight monetary policy stay in place when growth comes to an end? 3. Should the central bank have a clearly defined rule? The benefit of a rule is that it provides transparency and sets expectations, and expectations are essential for effective monetary policy. The downside of a rule is less flexibility, and loss of credibility if the central bank fails to meet its targets. If you answered yes to all of the above, then NGDP level targeting is for you. Personally, I agree that a central bank with a dual mandate should consider GDP. However, I think that the central bank should have some flexibility in targeting levels versus growth, and that growth is sometimes the more appropriate metric. Moreover, I think that a central bank like the Federal Reserve, that has a high level of trust and credibility, has more to lose from committing to a rule like NGDP level targeting than it has to gain, since failure to achieve the target would hurt its credibility. As it is, the Federal Reserve can consider the policy prescriptions of an NGDP target, while also considering Taylor Rules, asset prices, and other economic data when setting monetary policy.

0 Comments

According to NPR, this is the brainchild of Spike TV producer John Papola and libertarian economist Russel Roberts, together with rap duo Billy and Adam.

The Federal Reserve posted profits of $52 billion in 2009. The abnormally high profits were due to extra interest on assets held by the Federal Reserve; the Fed increased its balance sheet substantially as a result of its efforts to combat the financial crisis. Some of the extra interest came from increased holdings of Treasuries; some came from loans the Fed gave to bail out financial firms. After paying for its operating expenses, the Fed returned $46 billion of its profits to the U.S. Treasury.

PS. Hope I spelled "seigniorage" right. Microsoft Word, in its great wisdom, keeps suggesting "senior age". Spotted this question on Yahoo! Answers (I was looking for examples of non-moral values but that's another story):

What is NOT a function of the Federal Reserve? A. Giving short-term loans to banks B. Controlling the money supply C. Regulating depository institutions D. Lending money to businesses for investment This is an intro to macro classic. If you said D, that was the correct answer. At least until the financial crisis. Some of the recently added facilities look like they could fall into that last category. For example, the Commercial Paper Funding Facility, which buys commercial paper directly from issuers. That sounds a lot like "lending money to businesses..." Time to add E. None of the Above The Reserve Bank of Australia became the first G20 central bank to raise interest rates today, increasing its policy interest rates by 25 basis points to 3.25%. Of course, Australia has done very well through the financial crisis, relatively speaking. It's banks have remained pretty strong, China has continued to demand Australia's commodity exports, and Australia has only had one quarter of negative GDP growth. (Australia's real GDP fell 2.8% at an annual rate in 2008Q4. while in the United States, recessions are declared by the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee, many countries simply consider a recession to be in effect after two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth.)

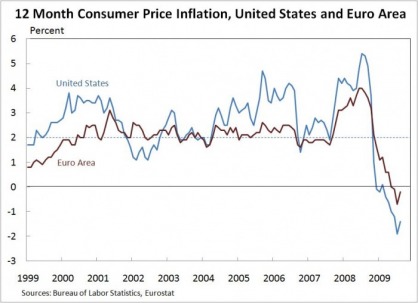

The RBA's decision to raise interest rates resulted in a drop in the dollar. With Australia raising interest rates, investors know that there are assets out there where they can get higher returns, so low-yielding Treasuries don't look like such a good deal, despite their safety. The decision is also a vote of confidence in the world economy, which could increase investor's expected returns on assets other than Treasuries. As Australia and other countries (possibly Korea?) start raising interest rates ahead of countries like the United States and Japan, keep your eye out for a revitalization of the carry trade, where investors borrow in countries with low interest rates, and invest in countries with higher interest rates. One of the House Financial Services Republicans' financial regulation reform proposals is increased oversight of the Federal Reserve, including an explicit inflation target. Explicit inflation targets, where the central bank announces a specific inflation rate it intends to achieve, are used by a number of central banks around the world, including the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, both of which aim for 12 month consumer price inflation near 2%. In recent years, the European Central Bank has managed to keep inflation closer to 2% than the Federal Reserve. However, targeting alone doesn't tell the whole story. The European Central Bank is charged with considering price stability first, and economic growth second. The Federal Reserve is supposed to consider both equally. Thus, one would not necessarily expect the two monetary regimes to have identical inflation rates, even if they were both explicitly targeting 2% inflation.

An explicit inflation target can be useful to help build confidence in a central bank and ground inflation expectations-- if the central bank can meet the target. If it can't, the central bank risks losing confidence. Among central banks, the Federal Reserve may be least in need of building confidence, due to its long, respected record. If public confidence in the Federal Reserve were to falter, implementing an explicit inflation target might help. However, even though the Federal Reserve has become the target of some public blame for the financial crisis, markets appear to still have faith in its ability to maintain price stability. Inflation expectations (which can be gauged by looking at the difference between the yields on regular Treasury notes and the yields on notes indexed to inflation) have remained close to 2% for the medium to long term. This suggests that an explicit inflation target would do little to improve the functioning of the Federal Reserve. Treasury Secretary Geithner testified at the House Financial Services Committee again today, underscoring the need for financial regulation reform. Nothing new was proposed, but Secretary Geithner reiterated the Administration's proposals and urged quick action on reform.

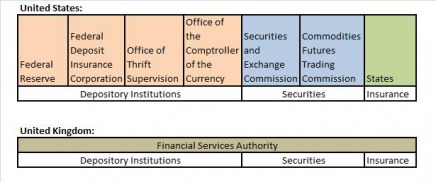

Chief among the proposals are: 1. The formation of a consumer protection agency that would regulate all financial services; including credit cards and mortgage brokers 2. Merging the Office of Thrift Supervision and the Comptroller of the Currency into one national bank supervisor; 3. Increasing the Federal Reserve's powers to regulate bank holding companies like Goldman Sachs 4. Creating a board with representatives from all the regulators to look for systemic risks and coordinate financial oversight policies 5. Increasing capital requirments and other regulations on large, "too big to fail" financial institutions, and using ex posts taxes on large financial firms to recoup the costs of any future bailouts The strategy for finacial regulation reform is to try to pass individual pieces of legislation addressing each issue. Some of these items will be easier to achieve than others. House Financial Services Republicans agree on the need for increased consumer protections and an over-arching body to look at systemic risks and coordinate regulatory policy among agencies. They differ on the future role of the Federal Reserve and on dealing with insolvent firms. Republicans propose stripping the Federal Reserve of all of its regulatory powers, and giving them to the national bank supervisor. The also propose a policy of no bailouts, even for systemically important firms. Both of these proposals seem rather radical (and very unlikely to be implemented with a Democratic House, Senate and Administration), and it is likely they are designed to pander to anti-Fed and anti-bailout sentiment in voters. Most of the Democratic proposals seem like reasonable responses to some of the problems that contributed to the financial crisis. However, I wonder about the plausibility of the plan to recoup bailout costs ex post. In a wide-spread financial crisis, where many or most large financial firms take large losses, an ex post tax could be a significant burden on the remaining (and as evidenced by their continued existence, the most prudent) financial firms as they attempt to recover. A thought that occurs to me-- which I am sure will be unpopular-- : in a situation where the risk was as widespread and systemic as it was in this crisis, not all of the blame rides on large financial firms. Many individuals benefitted from cheaper credit prior to the crisis; credit that was, in retrospect, too cheap. No regulations can foresee all future crises, and it is in part the responsibility of the government to adapt to evolving financial markets and address new systemic risks that arise. Perhaps when the government fails at this, it should bear part of the cost of fixing it. Financial market reform was an issue even before the financial crisis. (For example, see this GAO report.) Then, however, the catch-phrase was "financial market competitiveness." Large financial services firms answered to a multitude of regulators, while hedge funds slipped through the cracks. There was concern that complying with the United States's patchwork of regulators put a burden on the financial sector, and that burden might be enough to push financial services firms into other countries with less complex regulation. The United States was often compared unfavorably with the United Kingdom, which has one large regulator that oversees all financial services. Here is a simplified diagram of the two countries' regulatory structures (in reality, both countries have a number of additional agents involved in regulation): The trouble is, the UK's streamlined financial regulatory system doesn't seem to have saved it from the financial crisis. According to the IMF's April Global Financial Stability Report, the UK has had the second highest bailout costs (after the United States) among the G7, with estimated costs of 9.1% of GDP (the U.S. cost is estimated at 12.7% of GDP).

That doesn't mean that simplifying regulation isn't a good idea; in fact, it may go hand-in-hand with creating an over-arching regulator to look at systemic risks, as many have proposed. Moving away from regulating based on activity, and towards regulating based on firm, could also help alleviate concerns about products traded "over the counter", that is, not on regulated exchanges like the New York Stock Exchange. However, it suggests that consolidating regulators alone isn't a safeguard against crisis. This is my first post, so let's get right to the substance. I just received an email asking me what I thought about this article: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/jan/20/george-monbiot-recession-currencies |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed