|

I have an interest in governance and corruption, so I have to admit, I was a little bit excited when Jeremy told me he had to go to court for a traffic infraction.

By developing country standards, the police in Guyana aren't particularly corrupt, and from what I have heard, there has been a recent crack down on officers accepting bribes. However, any place where the official process for resolving minor traffic infractions is particularly burdensome, bribes have a way of becoming the standard process for resolving a traffic stop. Or, perhaps, in places where corruption is allowed to persist, officials have an incentive to make official processes especially burdensome. In any case, Guyana, like most developing countries, does not have the infrastructure in place to issue a ticket, let you pay it online, and follow up if you fail to pay. Resolving a traffic stop legally involves the moderately onerous process of reporting to the police station to pay a ticket, whose amount is determined transparently (in the case of speeding) or non transparently (in the case of pretty much anything else.) So bribes happen. Apparently the code phrase here is "let me buy you lunch." Jeremy's particular offense was crossing a double yellow line. This might seem like a no-brainer, but consider that often the lines in the middle of the road do not exist at all, and it is easy to get in the habit of paying attention to whether it is safe to pass, not whether the lines indicate it is legal. People also die regularly passing in blatantly unsafe conditions. I wasn't there, but Jeremy claims that he passed a very slow vehicle on a straight and clear section of road, not noticing the double lines. (A funny aside about double yellow lines-- recently the yellow center lines have been repainted on a number of roads around the periphery of Georgetown. In many cases, work crews have been sent to re-paint in black between the lines, because the first application of yellow paint was not straight or was placed such that the old yellow lines showed up in between the new ones. Infrastructure development at its best.) Anyway, Jeremy was pulled over for crossing double yellow lines while passing. Jeremy was not given the option of reporting to the local police station to pay a ticket. Instead, he was told to report to court the next week at 9:00 am and wait for his hearing. The officers couldn't say how much he might be fined. This all seemed a little suspicious, especially since it happened a couple days after Christmas (see "Everyone Gets Their Christmas Bonus Somehow"). Jeremy dutifully showed up at court the next week promptly at 9:00 am, as is his fashion. I regrettably could not come watch him, due to work. Jeremy's court appearance turned out to be decidedly undramatic. He sat for two hours waiting for his name to be called. It never was. Since most of the sessions were closed, he couldn't even sit in the court room to listen to other cases. After the morning session came to an end, he was told his name was no where on the docket, and he could go home. We came to the conclusion that the police officer who stopped Jeremy had never submitted the paperwork for his infraction. Maybe he never intended to. Maybe he told Jeremy to report to court, rather than allowing him to pay his ticket, in order to scare him into a bribe. Corruption is sometimes theorized to be a way around burdensome official processes. Jeremy's trip to court shows that even when the outcomes are relatively harmless, it can be a colossal waste of time that damages the reputation of a countries' institutions.

1 Comment

In Guyana, salaried employees traditionally receive a 13th month bonus-- the equivalent of one month's salary, paid as a bonus at the end of the calendar year.

This bonus, combined with the rush to buy gifts and traditional holiday foods, creates a surge in demand which I'm told pushes prices in the market up in the days before Christmas. Eggs in particular have a reputation for becoming outlandishly expensive. I decided to see if the anecdotes shared by my colleagues were reflected in price data. They weren't. There is no seasonal uptick in Guyana's consumer price index in December. (There is some macro evidence of the bonuses: currency in circulation spikes in January.) Assuming my colleagues' stories of spiking market prices are correct, why is there no increase in the CPI in December? I can think of several reasons.

I didn't tell him that I'd paid all my taxis extra that day, even the ones who'd asked the regular price, even though there didn't seem to be a shortage of taxis. Maybe for a short time during the holidays, the market just doesn't clear. Or maybe we pay a little extra, and we buy a little extra holiday cheer.  In Guyana, Christmas breakfast means Pepperpot. Jeremy and I decided to give the traditional recipe a go. It's easy to see why it's a Holiday favorite. The recipe combines a grab-bag of meat with cassareep (a sauce made from cassava), orange peel, cinnamon, cloves, onion, thyme, brown sugar, and hot peppers. We cooked it for three hours, and it filled our house with a savory mix of exotic and familiar Christmas smells. Despite the long cook time, the recipe was simple, and the meat came out very tasty. This recipe is definitely going to become a holiday family tradition. I guess this means we'll need to find a reliable source of cassareep in the U.S. In my search for a good pepperpot recipe, I read internet tales of counterfeit cassareep sold in New York City that turned out to be soy sauce. There are a couple things we'll change next year. First, we will try to find some fattier meat. We bought beef stew meat to avoid dealing with bones, but even after 3 hours of cooking, we never got that juicy, falling-apart meat that I've seen in Guyanese pepperpots. Second, we decided to substitute a couple of Jeremy's farm-grown habanero peppers in for the traditional wiri wiri peppers. The result was very spicy. Next year, we'll stick to just one. Most mornings I take minibuses to work. Sadly, minibuses in Guyana do not have a cute name on par with the "tro-tros" of Ghana, or the "car rapides" of Senegal (which were anything but "rapide".)

Most of the time, passengers pass the ride without talking much, as the buses are filled with the sounds of reggae, sappy R&B, or Christian music, depending on the taste of the driver. This morning, however, my entire bus had a conversation about what was wrong with kids these days. Complaints (imagine them in a Caribbean accent) included: 1. They don't own their own houses. ("I'm on my pension now and I'm not paying nobody!" 2. They won't work long hours at low wage jobs. ("I was workin' every day for GYD200! Except Saturday and Sunday.") 3. They don't cook fresh food. ("They're just stickin' it in the microwave!") 4. Their clothing styles are scandalous. ("They walk down the street and their bottoms just hang!") No mentions were made of walking a mile to school in snow, uphill both ways. It's been a while since I have posted on this site, but now that I am in Guyana, it seems like a good time to restart.

First, where is Guyana? I actually wasn't sure when I got my post, except that I knew my African geography pretty well, and I knew it wasn't there. Guyana is in northern South America, bordered by Venezuela, Brazil, Suriname and the Atlantic Ocean. Although it is geographically part of South America, and has some outstanding rainforest (or so I have heard), it is culturally and economically much more closely tied to the Caribbean. In fact, the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM) is headquartered right here in Georgetown, the capital of Guyana. The weather here is about 75 - 85 degrees all year. There are rainy seasons and dry seasons, but unlike in Ghana where the dry season meant no rain at all for months, the dry season here means it only rains every few days. Georgetown is 6 feet below sea level (we blame the Dutch) so flooding is a problem, but the city is working on improving the infrastructure. Despite the the nice weather, the beaches aren't particularly picturesque, because the ocean water is brown from the silt brought from the rainforests to the coast by the many rivers. Getting here by plane isn't too bad, but there are few direct flights. Most flights to Georgetown stop over in Trinidad. Sounds to us like a good excuse for all of you to book a vacation combining the Guyanese rainforest and the Caribbean beaches! I recently visited Monrovia, which in the words of P-Square, chopped my money. Food, accommodation, and transportation are much more expensive in Liberia than in any other West African country I have visited. It’s true that Liberia is a post-conflict country full of UN staff, who, when not struggling to help Liberia maintain its stability and get on its feet, are probably struggling to find enough things in Liberia to spend their money on. But Liberia also differs from other countries in West Africa in that the U.S. dollar is used in parallel to the Liberian dollar. Is it possible that dollarization could also contribute to higher prices? First, a couple of observations about money and prices in Liberia. The U.S. dollar and Liberian dollar are used interchangeably. There is no place that accepts only one. Generally, the U.S. dollars are used as large denomination bills, and the Liberian dollars are used in place of U.S. coins. (I didn’t see a single coin in Liberia.) Prices of imported goods in Liberian supermarkets are roughly the same as the dollar equivalent of prices of imported goods in Ghanaian supermarkets. Gas prices also seem to be similar, though a bit more expensive. It seems that the main difference in prices stems from differences in prices of services.

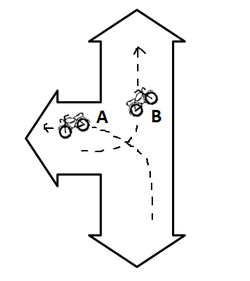

The fact that price differences are concentrated in services, or non-tradeables, makes me suspect that the high prices are in part due to dollarization, and here is why: in a non-dollarized economy, like Ghana, which uses the cedi, if the Ghanaian government pursues a loose monetary policy, the currency will depreciate relative to the U.S. dollar. This doesn’t affect the dollar price of imported goods—these are bought in dollars, so their price in Ghana cedis will just be inflated so that the equivalent price in dollars is unchanged. Other prices in the economy, however, are sticky. Employees have contracts with set wages, and people are used to paying a given price for hiring someone to sew a dress. As a result, the price of these non-tradeables stays constant in cedis, but becomes cheaper in dollar terms. (Note about monetary policy transmission in West Africa: In West Africa, business and consumer loans are much scarcer. So loosening monetary policy doesn’t lead to cheaper credit very quickly. It does, however, mean that cedi funds are more readily available to banks than U.S. dollar funds, which puts pressure on the exchange rate. So monetary policy transmission through exchange rates is more important in countries like Ghana, and happens more quickly, relative to transmission through interest rate mechanisms, compared to countries where large portions of the population have access to credit.) What this means is that Ghana, if has a trend of depreciating currency, can have low overall prices in dollar terms because, in dollar terms, prices for non-tradeables have fallen. Liberia, since it is dollarized, won’t see this effect. If Liberia prints more Liberian dollars, the exchange rate may change, with the value of the Liberian dollar declining, but prices in dollars will stay the same. This does, of course, attribute a level difference to an effect that applies to differences in rates of change, and my observations regarding prices of goods and services are anecdotal (Liberia doesn’t have good CPI data.) If you have comments on the plausibility of the theory, please comment!  Tamale has a number of traffic norms that would make a driver's ed teacher turn to drink on the road. A classic example is the "Tamale turn", pictured at left. In Tamale, if you are making a left turn off of an arterial, and there is vehicle waiting to turn left ON to the arterial, rather than pass in front of the other vehicle, you pass behind them, while they simultaneously turn onto the arterial. One can see why drivers might think this makes sense. Both vehicles can turn at once, and if the arterial is busy, the vehicle waiting to turn on to it can take advantage of the other vehicle slowing down. But as traffic gets denser, the Tamale turn becomes more hazardous. If there are several vehicles waiting to turn on to the arterial, the vehicle turning off the arterial has to negotiate a route behind the turning vehicle, and in front of the waiting vehicles, who may not be on the lookout for a turning vehicle. And more vehicles in the intersection at once raises the risk of a collision as well. As Tamale's traffic worsens, many similar traffic norms, such as running red lights and passing on the right, technically illegal but general practice in Tamale, will become less efficient and more hazardous. But they will already be ingrained as the standard. What to do? Some ideas: 1. Give driver's licenses based on merit rather than bribes, to give drivers an incentive to learn the rules on the books. 2. Ticket drivers for practices that threaten public safety rather than focusing on trivial offenses easy to convert to payouts. Your additional ideas are welcome in the comments! Clearly, the nations of the world are not going to line up to let me randomize their monetary policy. But what if I could convince one to do so?

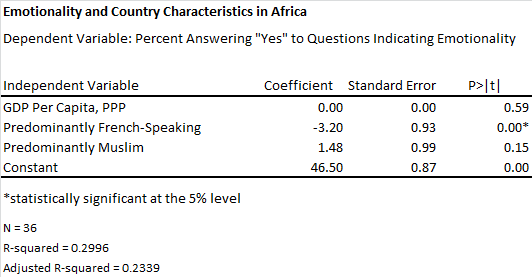

Randomized control trials (RCTs), when ethical and possible, present the most reliable way to measure the impact of policy. Units of randomization, for instance people, are put into a treatment group, who gets a program or policy, and a control group, that doesn't get the program or policy. You compare outcomes for the two groups to see the impact of the program. The key to the validity of the RCT is that the sample size has to be big enough that when you randomly divide into treatment and control, there are no important systemic differences between the two groups. Randomization isn't used to evaluate macroeconomic policies for 2 reasons: 1) it is usually too important for people to allow it to be randomized, and 2) it has to be enacted at a high level-- national or maybe state or province-- so it is difficult to get a large enough sample. But what if we randomized, not by entities like people or countries, but across years? For example, what if the Federal Reserve allowed me to randomly change the policy interest rate by +25 basis points, 0 basis points, or -25 basis points? Over a long enough time frame, the periods that fall into each randomization group should be statistically the same on average. This would allow us to look at the effect of the interest rate change on the economy. Of course, there are some kinks to be worked out. Similar to spillover effects, policy changes have impacts across multiple periods; however, these could be measured and accounted for. Another problem is checking the balance of the randomization. There would be no equivalent to a baseline, and you couldn't stratify, since you don't know the attributes of future time periods in advance. These problems would imply that you need a very large sample size. There are certainly other methodological challenges I haven't thought of. I imagine I will have plenty of time to think through them before the first problem-- the fact that politicians, who insist they can control things they can't, would never randomize something they can-- is solved. But if anyone hears about a central bank looking for a monetary policy consultant, let me know. Gallup recently published results of a global poll on people's propensity to express or report feeling emotions. The Washington Post has a nice color-coded map of the results here. While some regions exhibit trends-- the Americas are bubbly with emotion, while the former Soviet Union is more somber-- Sub-Saharan Africa has a lot of variation. What country characteristics might be associated with increased emotional expression in Africa? I decided to test the relationship between emotionality and wealth as measured by PPP-adjusted GDP per capita, predominant language (a proxy for colonial influence by France or England), and whether at least half the population was Muslim. I used a linear OLS regression; results are below: There was no significant relationship between wealth and emotionality for the African countries. Countries with a Muslim population of at least 50 percent had a slightly higher average emotionality score, but the difference was not statistically significant.

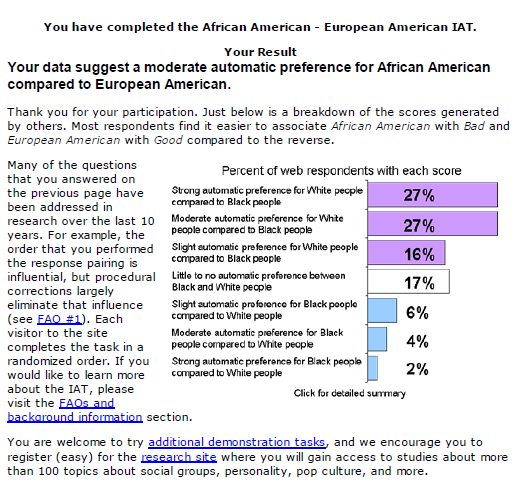

People in Francophone Africa were, on average, 3 percentage points less likely to report expressing or feeling emotion, a result that was statistically significant. This may not sound like much, but it's a whole standard deviation below the mean emotionality score. (The model also explains more than a quarter of variation in African countries' emotionality scores!) So why are the Francophones less effusive? A couple hypotheses: 1. Maybe when translated into French, the survey was less likely to result in positive answers for some reason. 2. The Francophone variable might actually be capturing regional variation, such as lower emotionality in West Africa. 3. The French colonial cultural influence may have included elements of less emotional expression. The first issue is hard to address (language and cultural translation is always an issue when trying to compare social tendencies across cultures.) Putting in regional variables could address the second issue. Another interesting thing to look at would be the impact of political instability. My data, in .dta format for stata, are here: /uploads/1/7/1/1/1711915/africa_emotionality.dta I took the Implicit Association Test for race at Project Implicit (you can register to participate in online implicit association psychology research.) My results surprised me: I expected to be neutral (don't we all think/hope we are), or if anything, to have a slight preference for European American, given that I am myself a European American.

I wonder if my results are related to the community-oriented culture in West Africa. In Ghana, if you are in trouble, you know people will help you. I would have been unsurprised to find I had implicit associations between African Americans and words like "community", "help", or "friendly", as a result of my experiences with Africans. In more individualist America, I don't trust that bystanders will help if I'm in trouble. But there are positive words I would associate that culture too-- words like "freedom", "privacy", "efficiency" or "merit". I wonder if the words selected for use in the implicit bias test are more likely to be associated with traits I like about Ghanaian culture than the traits I like about American culture. I think the important take away, though, is that it is very easy to make implicit but fallacious generalizations-- in my case, that only European features imply American culture, or that African features only imply Ghanaian culture. Living in another culture certainly challenges your preconceptions-- I remember when Trayvon Martin's death made the news, thinking, "Black people wear hoodies??"-- but it's important to remember that it doesn't make you immune from internalizing new biases. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed