|

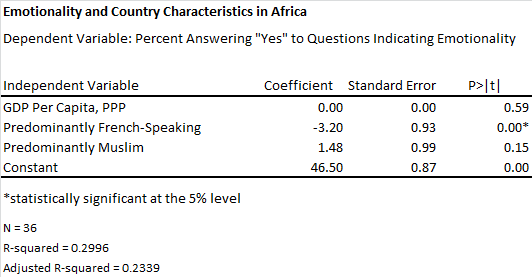

Gallup recently published results of a global poll on people's propensity to express or report feeling emotions. The Washington Post has a nice color-coded map of the results here. While some regions exhibit trends-- the Americas are bubbly with emotion, while the former Soviet Union is more somber-- Sub-Saharan Africa has a lot of variation. What country characteristics might be associated with increased emotional expression in Africa? I decided to test the relationship between emotionality and wealth as measured by PPP-adjusted GDP per capita, predominant language (a proxy for colonial influence by France or England), and whether at least half the population was Muslim. I used a linear OLS regression; results are below: There was no significant relationship between wealth and emotionality for the African countries. Countries with a Muslim population of at least 50 percent had a slightly higher average emotionality score, but the difference was not statistically significant.

People in Francophone Africa were, on average, 3 percentage points less likely to report expressing or feeling emotion, a result that was statistically significant. This may not sound like much, but it's a whole standard deviation below the mean emotionality score. (The model also explains more than a quarter of variation in African countries' emotionality scores!) So why are the Francophones less effusive? A couple hypotheses: 1. Maybe when translated into French, the survey was less likely to result in positive answers for some reason. 2. The Francophone variable might actually be capturing regional variation, such as lower emotionality in West Africa. 3. The French colonial cultural influence may have included elements of less emotional expression. The first issue is hard to address (language and cultural translation is always an issue when trying to compare social tendencies across cultures.) Putting in regional variables could address the second issue. Another interesting thing to look at would be the impact of political instability. My data, in .dta format for stata, are here: /uploads/1/7/1/1/1711915/africa_emotionality.dta

14 Comments

"A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It's where the rich use public transportation." If the truth of this statement is not immediately apparent, you probably have never commuted in a West African city. Accra needs a lot of infrastructure improvements, but one thing it does not need are more cars. After work, I can run the two miles to my gym faster than I could take a taxi there. Traffic is similarly bad in Kumasi and Dakar, and is rapidly worsening in Tamale. Driving is no picnic in American cities, either. The difference? In American cities, rich people often choose to live in places accessible to public transportation, and their taxes and patronage support transit systems that benefit the rich and poor alike (even LA is getting on the bandwagon). In developing country cities, the poor take low quality public transit, such as trotros and shared taxis, while the rich clog the roads with their private cars and taxis. While roads in developing country cities could certainly be improved (I would love to see someone apply traffic light efficiency models to Accra traffic), the reality is there is limited capacity to expand current roads or build new ones in the middle of the city. Poor people are already taking public transport. That leaves one viable solution to traffic in developing country cities: getting rich people to convert to public transport. For practical and cultural reasons, this is an uphill battle. First, the main reason rich people use public transport in developed cities is not because they are altruistic, it is because it is faster and easier than driving. Accra currently has no public transit system that can rival the speed and efficiency of a private car. Considerable investment would have to be made in a rail or bus system with widespread coverage and efficiency in order to convince people to convert. Second, there is a cultural attachment to driving. Owning a car is a definitive status symbol in West Africa; taxi drivers are often confused when I, a person who apparently has the money to take a taxi, choose to walk. Improving traffic in Accra will require a commitment from the wealthy and elite-- both foreigners and Ghanaians-- to get out of their air conditioned Toyota Landcruisers and both fund and use public tran A 20-year-old recently became internet famous for punching a man who joked about raping a drunk girl on the street one night. When is it ethical--and more importantly, efficient-- for individuals to take justice into their own hands? This question is particularly salient in Ghana, where vigilante justice is a common response to crime, and that justics goes up to and includes death for perpetrators of rape or severe property crime.  Actually, I did see what you did there. And I have a machete. Justice generally serves two economic purposes: to make an injured party whole, and to provide a disincentive against bad behavior. Vigilante justice tends to be focused on the latter. If you doubt this, just wait for the next Batman movie-- I guarantee my dear Bruce Wayne will wreak more economic havoc as the caped crusader than he will provide in redress. Vigilante justice comes at a high price, to the executioner, society, and to innocent parties who fall mistakenly fall victim to it, and is limited in the benefits it can provide.

In order to be justified then, vigilante justice must have a very high deterrent benefit. This will generally only be the case when legal justice systems completely fail to act as deterrents to morally reprehensible acts. It seems to me that the woman's decision to punch the rape joker fits this criteria. No court in the United States would ever provide any kind of consequence for comments like this man made. To me, the welfare gain from the chilling effect (amplified by publicity) this will have on such jokes, which quickly turn a fun night out into a stomah-clenching affair that can haunt a woman for months (if not years), clearly outweigh one guy having a sore nose for a couple weeks. Similarly, in Ghana, legal remedies are a poor deterrent to crime. (Especially legal remedies that are actually legal, NOT including police beating suspsects.) Even in clear cases where suspects are caught red-handed with eyewitnesses present, criminals often walk free. Two friends of mine were beaten with bricks a couple years ago, and one of the assailants was captured at the scene of the crime, but was released after several months of courtroom circus. Death by beating, however horrific, not only provides a clear disincentive to crime but permanently removes a criminal from society. So can vigilante justice be morally and efficiently right? Yes. Does that mean it should go unpunished? No. The fact that vigilante justice can have a high cost for falsely accused victims means that executioners must have a disincentive to engage in vigilante justice unless they are sure of its benefitcs. Punishing, or potentially punishing, perpetrators of vigilante justice provides that disincentive. So the woman who punched the joker should be potentially liable for damages, and those who engage in mob justice beyond that necessary for defense should be liable under assault laws, to prevent vigilantes from risking targeting those not truly guilty. This may seem like a rather extreme position; it is certainly influenced by living in situations where law enforcement seems ineffectual. However, the truth is, society engages in vigilante justice all the time. In the U.S., however, it is usually psychological, not physical: when someone cuts in line, they are often shamed, but not punched. Vigilante justice is an appropriate response to those inevitable situations where the law has no reach, but how it is exercised must be limited by disincentives against its most extreme forms. Last Saturday night around midnight, I was standing in the middle of a street in Tamale, trying in vain to beg or bribe a taxi driver to stop and take a dying man to the hospital. I hadn’t seen the motorcycle collision that injured this man and one other, but the small crowd, the battered bikes, and the bloody, limp bodies told the story clearly. My makeup, blond hair (combed for once), and red dress, which correctly marked me as a foreigner on my way to a dance club—normally very desirable fare for a taxi—suddenly carried little cachet. As multiple taxis turned me down, two of the man’s friends began a futile and possibly fatal attempt to load him onto the back of the motorcycle. His neck and limbs flopped sickeningly as the motorcycle sparked to life and died repeatedly.

In the end, the only way we could convince a driver to take the man to the hospital was to have a white person accompany him. A friend of mine drove ahead of the taxi on his own motorcycle, carrying one of the man’s friends. We paid the driver four times the going rate. As they drove away, a woman watching the scene remarked to me, “Of course the taxi driver can’t take the man. When he gets to the hospital, they will hold him responsible and make him pay if the man can’t.” Welcome to a world where individuals have the liberty not to have health coverage, and face the consequences for how they exercise that liberty. In Ghana, you don’t get treatment—sometimes even life-saving treatment—until you prove you can pay for it. Doctors will sit and watch you bleed while your friends and family cobble together money for payment, or rush to renew your health insurance policy. I once saw a four-year-old boy delivered to a rural health clinic after he ran onto the highway and was hit by a motorcycle. There was nothing the clinic could have done to save him. His mother spent his last moments not by his side, but running desperately through the village to get his insurance card. The issue of allowing indigent or liquidity-constrained individuals (those who could pay back their medical bills over time) to die aside, the serious economic issue here is that when the default assumption is that people cannot pay for health care, there are negative externalities that mean even those who can pay for care may not get it promptly, and as a result, may have worse outcomes. A man with thousands of cedis in his account should be able to get a taxi to the hospital; he should not be left on the road because the drivers fear he will be turned away on the hospital steps. A child with insurance should be treated promptly; he should not be left bleeding on a clinic table while his mother runs for proof of insurance. Those who support universal health care, or an insurance mandate, should not fail to recognize the costs, in terms of our government budget deficit, burden on the poor, and loss of economic freedom. However, those who are opposed to it should recognize the full costs of that liberty as well. I often fantasize about plots to confound muggers and highway robbers. (I know, this probably suggests I need to go on more dates.) One of my favorite—and less disturbing—plots involves buying a knock off designer purse, filling it with rocks, and prancing around with it at Gumani intersection after dark. I take particular pleasure in picturing how the inevitable purse snatcher will stagger under the bag’s surprising weight, and the look of dismay on his face when he opens his hard-won prize.

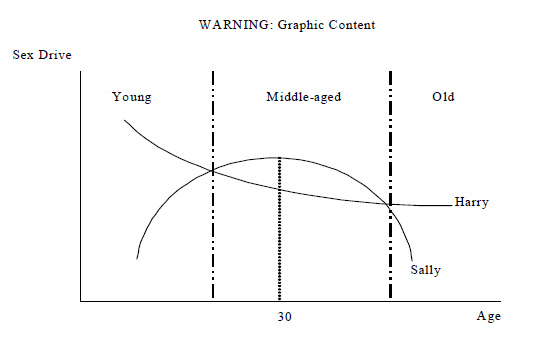

This paper by Cormac Hurley of Microsoft suggests this might not be such a bad idea. The paper models the economic decision made by an attacker, taking into account the cost of initiating an attack, the payout if successful, the total number of viable targets, and the density of viable targets among the general population. The model shows that to make attacks economical, ability to identify a subpopulation with a high density of viable targets is key. The paper’s findings have important implications for how we might approach crime reduction strategies in Tamale. Generally, one can try to deter crime by increasing the cost of engaging in it, or by reducing the benefits. Increasing cost: You can do this in a few ways. First, you can increase the penalty if the attacker is caught. You can also increase the likelihood that the attacker is caught. Either way, you increase the “expected”, or average, penalty for engaging in crime. (The rarity of catching criminals in Tamale is the main reason I am sympathetic the high penalties imposed in vigilante justice here.) You could also do this by increasing the cost of attempting an attack regardless of penalty, say by forcing attackers to sustain injury in order to get a payout. Reducing benefits: You can reduce the benefits of attacks by reducing the frequency with which criminals get a payout (reducing the number of viable victims), or by reducing the amount of the payout if the attack is successful. While this may all seem obvious, the Hurley paper’s model sheds some light on the efficiency of different approaches. The model suggests that reducing the frequency with which attackers get a payout can have a much larger effect than increasing the cost of crime or reducing the amount of the payout. For instance, in one example in the paper, if an attacker can successfully identify viable victims 99% of the time, and the ratio of the payout to cost is 100, the attacker will end up attacking 32% of viable victims. If you reduce the payout to cost ratio to 20 (you could do this by reducing the payout by 80% or by increasing costs by 400%), then the attacker will attack about 15% of viable victims. However, if you reduce the attacker’s ability to accurately identify victims from 99% to 95%, the attacker will only attack 4% of viable victims. The challenge with crime in Tamale is that the cost of committing it is pretty low, due to lackadaisical policing, and the ease with which attackers can identify viable victims: white people out late are almost always a viable target. Increasing police vigilance will be difficult to effect, especially without risk of repercussions such as curfews and travel warnings that might lead organizations to avoid Tamale. The good news is that a strategy we can more easily implement—decreasing the percent of Tamale expats who are out late and are actually viable victims—is likely to be a much for effective strategy anyway. So what can you do? Make sure you are not a viable victim. Don’t carry anything that could be a payout for an attacker. Don’t do things that make you an easy target, like get drunk or carry bags that are easy to take away. Travel in groups, and in areas where help will come quickly. You have probably realized that a corollary to this is that increasing the total number of people who are out late, and are not viable victims, could be a very effective strategy to deterring crime. However, in the case of Tamale muggings, being a non-viable victim still carries risks, and I am not advocating that anyone go out at night with the goal of being a “false positive” in an attempt to reduce general crime. But if you see me at Gumani junction with a fancy bag that looks awfully full, you’ll know what’s up. This is possibly the most awesome economics paper I have read in a while, containing the most awesome graph I have seen in a long time:

For Easter weekend, I planned to drive my motorcycle to Ouagadougou from Tamale. It’s not a particularly long drive, perhaps 6 hours (my record is 10 hours on the road.) My plans were thwarted at the border, where I learned that to take the moto into Burkina, I needed the deed in order to prove that it wasn’t stolen. I had deliberately left the deed in Tamale to make sure I wouldn’t lose it.

The good news is that Burkina customs and border control officials never implied that I could get the moto in with a bribe. This was even more surprising, because I asked if I could bring it by paying for a license in Burkina, which, in retrospect, would have signaled that I was willing to pay a decent amount to get it in. I ended up leaving the motorcycle with the Ghana border control, who refused even a modest dash as a thank you. (I later heard a possible explanation for why the Ghana border police refused my dash—it was small peanuts to them. Allegedly, to get a post as a border patrol officer, you have to pay someone a dash on the order of GHC 1,500—but an official can make that much in a week from bribes from traders who want to avoid the even more onerous Ghana import taxes. Compared with that kind of money, a GHC 10 dash is worth forgoing in exchange for someone’s good opinion. ) I asked about leaving the moto with the Burkina border control. The officials there declined to keep it. However, the border head official tried to console me, saying, “Mais ca va—je veut dormir avec vous!” In English: “It’s okay—I want to sleep with you!” NPR recently featured a segment on tipping, positing that while many people believe they tip to reward good service, they actually tip out of guilt for being served by another. The segment points out that people tend to tip at fairly constant rates, regardless of how good the service is, and more interestingly, the services that conventionally require tips in the United States are those where the person receiving the service is having a lot more fun than the server. People at restaurants and hotels tip; people at the dentist do not.

Guilt seems to make up a large share of my (admittedly under-average) emotional spectrum, so I find this very compelling. The segment points out a downside to this: tipping out of guilt may not be efficient. Tippers may give an amount larger than the value of the service to them, and tips that don’t vary with service quality don’t provide incentives for better service. Tipping norms in Ghana are quite different from those in the United States: tips are not necessarily expected for restaurant service, but for help with directions, with making a large purchase, or with loading bags onto a bus, a tip, or “dash” is expected. (“Dash” functions as both a noun and a verb.) Often, the services you are expected to dash for are services you don’t even want, and the tipper may even give money just to get someone to go away. The role of guilt in tipping is compounded in these situations by the uncertainty foreigners may have regarding tipping norms and by the income disparity between the average foreigner and the people who do these types of jobs in Ghana. The trouble with this is that the efficiency of the tip is further diminished. While guilt may make me a generally good tipper, as an economist, I also feel guilty when I tip for poor service or services I don’t want, thus providing poor incentives. Here is my advice on tipping in Ghana to maximize good incentives: Restaurants: Tipping is not mandatory for food service, though it becomes more expected the more upscale the venue. I highly recommend giving small tips/dashes that are very sensitive to the quality of service. At a local eating spot, 1 GHS is a good tip for basic service, and will likely get you a little extra attention next time you visit. At a nice restaurant in Accra, a 10% tip for good service seems to be well-received. The rarity of tipping in Ghanaian restaurants presents an opportunity to tie tipping to good service, so I would urge varying tips accordingly, giving nothing for poor service, and large tips for good service. Bags: If someone helps you carry your bag, it is very much expected you will give a dash. If you don’t want to, then be firm about carrying your own bags. Bus baggage: Small dashes are often expected for loading your bags under a bus. It is hard to avoid using this service. This is the context where I have found demands for dashes to be most outrageous. A dash should not be mandatory for this—I have seen supervisors yell at men who demanded a dash before loading bags. I would recommend resisting anyone who demands one before helping you. The dash should also not be large. I once encountered a man who refused my 1 GHS dash and demanded 2 GHS. I gave him nothing. I would not give more than 1 GHS unless your bags are many, or you receive some special assistance with them. Note that a dash for loading should not be confused with an actual fee for baggage. Directions: You should not have to pay a dash for directions. If someone walks a long way with you to show you where something is, a dash may or may not be demanded. If you don’t want to give one, don’t accept the escort. Assistance with purchases: If someone helps you locate, select, bargain for, and complete a substantial purchase, a dash may be in order. Things to consider: how much help you received, how much time and money you saved as a result of the help, and whether the person got any financial gain from your purchase. Generally, anyone who approaches YOU about buying something doesn’t need a dash. Household errands: If you have a guard or groundskeeper, the person will often run errands for you. You should dash to compensate for their travel costs and efforts. Professional services: Professional services outside a person’s normal job may require a dash, depending on the job and the organization a person works with. As an example, I had a document notarized by a judge in Tamale, and I paid a 5 GHS dash for his time and trouble. Stealth window washing: One of the strangest things about Accra are stealth window washers, who swoop in on a car waiting at an intersection, squeegee the front windshield despite the driver’s protests, and then demand a dash after. No matter how guilty you feel, please, please do not dash for this or other unwanted services that are forced on you; you will only encourage the practice. Further advice on tipping in Ghana (or anywhere else)? Please contribute in the comments! This weekend, after a delicious dinner, some friends and I visited a rooftop drinking spot in Osu. As I slowly drove my motocycle into the crowded parking lot, a man reached out, put his hand on my leg, and slid his hand up my skirt as I went by on the moto. It took me a moment to register what had happened, and by that time, I had passed the group of men, and wasn’t even sure who had done it. After fuming for several minutes, I joined my friends, had a double whiskey, and did my best to forget about the incident and enjoy the rest of the night.

As I write this, several days later, I am still furious—furious with the man, but more furious with myself for failing to give the man any disincentive to repeat his actions. The options were many: yell at the man; report him to the police; hit him; run over his foot with my moto; or in my most vengeful fantasy, castrate him with my moto keys. Why didn’t I do any of these things? It wasn’t that I am incapable of standing up for myself. For the most part, it was simply because I wasn’t quick enough to react, but riding away had its advantages: I wasn’t physically hurt, I got out of a potentially harmful situation quickly, none of my friends had to be involved in a mess, and I was able to move on and continue my night. It’s hard to imagine a better outcome had I chosen to confront the man—but at what cost did this efficient short-term result come? What does it take to prevent this type of behavior? Minor physical assault and sexual harassment is not uncommon in Accra. My recent experiences include: · A man grabbing me around the waste and pull me away from my friends to try to get him to dance with me at an outdoor dance spot. I peeled him off of me and started yelling at him; another Ghanaian intervened and convinced him to leave us alone. · A man repeatedly came up to my friends and me in a dance club and rubbed against us, even though we were not dancing. After asking him three times to stop, I told him to “F-k off” and shoved him. He drunkenly fell on the ground and then went away. · A man on the street grabbed my hand as I was walking by him one evening and would not let go. I dug my keys into his wrist as I twisted my hand free. He let me go on my way. Let’s be frank—women face these types of encounters everywhere. I have a close friend in New York for whom catcalls are a humiliating but regular part of her daily commute. She has experimented with every type of reaction I can think of: anger, humor, honest conversation, and simply ignoring it. Nothing seems to make a difference. Is a man with a key gouge on his wrist less likely to try to grab a woman’s arm than one who got away unscathed? The truth is, I don’t think any reaction from a victim of harassment is enough disincentive to put a stop to this behavior. To be an effective deterrent, punishment must come from broad society. Men who sit on steps and catcall in New York City should face the disapproval of the grandmother next door and the scorn of the respectful men who pass by and see them as the boys they are. Men who assault women in Accra bars and clubs should be unwelcome in those spots, and those who grab women on the streets should be ostracized by other vendors there, who face lost business when women avoid those spots. In some cases, this happens. Too often, it doesn't. As long society fails to punish men for this behavior, a they will continue to bet that victims won't punish them either. I have no quantitative evidence to support this, but I get the impression that prices are stickier in Ghana than in the United States. My theory is that this is, ironically, because Ghana lacks sticker prices.

Most people buy things in the market, and they just "know" the price. If someone tries to charge them higher, they won't buy. My guess is that changing common knowledge of a price is actually a lot harder than just changing a sticker price. Could somebody do a study on this please? I recommend an RCT in isolated markets where you select half of the markets to go to sticker prices, where you provide the stickers. Those markets operate with the stickers for a few months, where the control markets continue to operate without marked prices. Then you introduce a price shock for, say, tomatoes, send out mystery shoppers, and see where prices change more quickly. I would do it myself but I am busy. |

About Liz

I have worked in economic policy and research in Washington, D.C. and Ghana. My husband and I recently moved to Guyana, where I am working for the Ministry of Finance. I like riding motorcycle, outdoor sports, foreign currencies, capybaras, and having opinions. Archives

December 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed